Recording: ‘Beneath the Beech Tree’

Here is my recording of a lyric composition I wrote using the melody from Jim Causley’s ‘Home’. The composition is a rough translation of Virgil’s 'Eclogue 1' which I have titled ‘Beneath the Beech Tree’:

I wrote the words for this composition and performed it inspired by two sources: the first, a Latin text, written by the Roman poet Virgil in the 1st-century BCE; the other, a song called ‘Home’, written and sung by Jim Causley, a musician from Devon, featured on his 2016 album ‘Forgotten Kingdom'.

As it happened, while translating Virgil’s first Eclogue, I found myself marvelling at the extent to which it resonated with Jim Causley’s piece ‘Home’. So, sitting down at the piano, I reworked my translation to fit the melody of Jim’s song…

Virgil’s ‘Eclogue 1’

Virgil's ‘Eclogues’, also known as the ‘Bucolics’, are a collection of 10 poems composed in Latin dactylic hexameters sometime between 42 and 37 BCE.

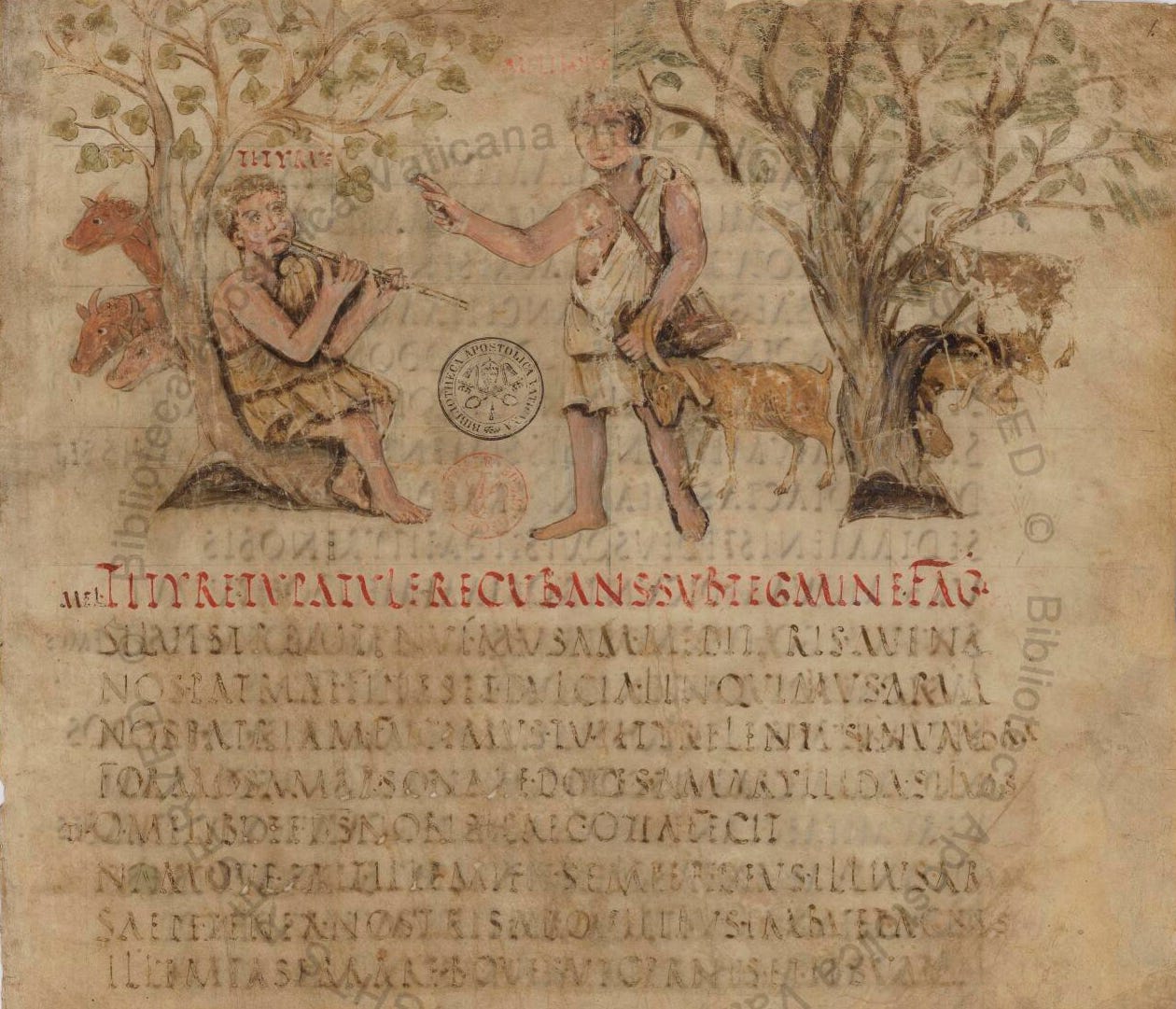

The very first poem of the collection, Eclogue 1, tells of an encounter between two characters: Tityrus, a shepherd; and Meliboeus, a goatherd. The pair meet as Meliboeus is driving his goats along the road and Tityrus is playing his pipe in the shade of a beech tree.

Tityre, tu patulae recubans sub tegmine fagi

silvestrem tenui Musam meditaris avena;

nos patriae fines et dulcia linquimus arva.

nos patriam fugimus; tu, Tityre, lentus in umbras,

formosam resonare doces Amaryllida silvas.

Full Latin Text: P. Vergili Maronis Ecloga Prima

Tityrus, lying there, beneath the spreading cover of a beech-tree,

you entertain the woodland Muse, on a slender shepherd’s pipe.

We are leaving the sweet fields and the borders of our homeland:

we are fleeing our country: you, Tityrus, idling in the shade,

teach the woods to echo with the song of ‘lovely Amaryllis’.

Full English Translation: The Eclogues

Genre

From the very outset, Virgil’s text places itself firmly within the poetic tradition known as the pastoral genre, a tradition that idealises rural life, the beauty of the natural world, and rustic simplicity. The Eclogues themselves are set in a fictionalised version of rural Italy, and depict the lives and loves of shepherds and other country folk.

The poems are suffused with the sort of language and imagery found in textual predecessors from the ‘pastoral’ genre. Foremost amongst these textual predecessors are the ‘Idylls’ of the Greek Hellenistic poet Theocritus. Virgil alludes heavily to the Theocritean poems, re-examining many of the norms of the pastoral tradition that they had established, whether that be their metre, their imagery, or even the names of their Greek characters. ‘Tityrus’, for example, one of Virgil’s interlocutors, is a named character in Theocritus too (he appears in Idylls 3 & 7).

But, while taking inspiration from the Theocritean world, Virgil also reinterprets his Greek Hellenistic model.

In the case of Eclogue 1, Virgil disrupts the bucolic idyll of the world Tityrus inhabits (where he lies beneath a beech tree playing a reed flute) by introducing political and social strife. This comes in the form of Meliboeus. While Tityrus embodies the pastoral vision, Meliboeus’ arrival marks the intrusion of a less romantic reality.

As a dispossessed, migrating goatherd, Meliboeus is somewhat antithetical to the Arcadian paradise. The artful interlacing of tu (you) and nos (us) forms a structure known as a ‘chiasmus’ that leaps out at the reader at key metrical junctures, bringing into stark relief the contrasting fortunes of the two men: Tityrus, ‘destined to relax in the shade, teaching the woods to sing’; Meliboeus, ‘fated to abandon his fields and wander far from home’. In the exchange that follows, Meliboeus describes how his goat has recently given birth and abandoned twin goat-kids in the brambles, an ominous sign of his desperation.

Socio-political commentary

Later in the poem, the characters discuss an anonymous ‘godlike young man’ who holds sway in Rome (deus… illum iuvenem 1.42). The anonymity is perhaps deliberate, reflecting the political uncertainty and ever-shifting political cast of the era. No sooner than one Roman general had risen to the top, they were invariably proscribed by their enemies and displaced by a rival. Reading the poem in retrospect, however, it is tempting to interpret the references as referring directly to the future emperor Augustus, then known as Octavian, the founder of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. On this reading, the implication appears to be that Meliboeus represents a Roman farm-worker of the 40s BCE facing dispossession.

Roman political and social reality also creep into the poem through subtle allusions to civil war. When Meliboeus sings of how a veteran Roman soldier has dispossessed him, that soldier is described not only as miles barbarus (‘a barbarian soldier’), but also as impius (‘godless’ 1.70). Here, barbarus implies ‘blood-stained’ as well as its other meaning ‘foreign’, while impius connotes not only ‘one who has abandoned gods’, but also ‘one who has taken part in a civil war’ (compare, for instance, impia proelia in Horace’s Carmina 2.1.30). These more oblique references to civil war are later reinforced by the more explicit use of the word discordia (often used to connote ‘civil strife’ or ‘civil war’ 1.71).

Virgil himself lived through this period of political and social instability in the Late Roman Republic. The years following the Roman Civil Wars of 49-45 BC and the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC saw a period of dispossessions during which many small-scale landholders and farmers across Italy were evicted from their land. In particular, Virgil’s native province, Mantua, is known to have suffered heavily at the hands of commissioners appointed by Octavian to find lands for the settlement of discharged veterans. The grammarian and textual commentator Maurus Servius Honoratus, for example, records in notes to the Eclogues that, in 42 BC, following Octavian’s victory over Brutus and Cassius at Philippi, farmlands in Cremona and Mantua were seized for the resettlement of veterans.

Although it is typically unwise to read first-person speech in texts as echoes of an author’s own autobiographical experiences, a general awareness of a text’s historical context should help inform our reading. In this case, the read-across appears relatively water-tight.

Metapoetics

Setting aside the socio-political, it is also worth noting that in Eclogue 1, Virgil appears to play with ‘metapoetics’. The term ‘metapoetics’ describes poetry that is self-aware and comments on itself. This poem, for instance, is metapoetic insofar as it explores its own poetic genealogy by rewriting motifs used in Theocritus’ older Greek poems.

Whereas, in Idyll 1, Theocritus chooses the shade of a pine tree as his locus amoenus (‘idyllic setting’), Virgil, by contrast, chooses to place his shepherd beneath a beech tree. Should we read Virgil’s arboreal substitution as a conscious correction of the original?

On a practical level, pines are low-branching and slender trees which drop pine-cones and needles, making them uncomfortable places to rest under. Beeches, meanwhile, have soft leaves and a shady canopy. By offering a more suitable location for pastoral contemplation, does Virgil correct his predecessor?

In more poetic terms, pine trees, like the cypresses or poplars, were old and established trees in the Greek poetic tradition. Many species of pine are native to Greece and the pine is a recurrent image in Theocritus’ poetry. By contrast, the common beech tree (fagus sylvatica) is native to North Italy, not typically found anywhere in Greece south of Thessaly and certainly not an established poetic tree. The prominent positioning of ‘fagi’ in the very first sentence of Virgil’s entire collection suggests that the beech is in some way symbolic or representative. Is this beech tree the first signpost indicating that Virgil will weave into his Greek predecessors a new revisionary, Roman outlook?

Metapoetics and the reinterpretation of Greek themes in a Roman vision recur time and again throughout Virgil’s poetic oeuvre. They recur in the Georgics, where Virgil rewrites Hesiodic themes, and, ultimately, they culminate in the Aeneid, in which Virgil synthesises the full sweep of Homeric literature.

Jim Causley’s ‘Home’

The sleeve-notes on Jim Causley’s 2016 album ‘Forgotten Kingdom’ observe that ‘[Jim] mixes songs of love and loss (whether that be a human or a homeland).’

In Track 6, titled ‘Home’, Jim’s first-person narrative voice, reflects on the displacement experienced by West Country locals who find themselves driven out of their local areas by rising house prices and demand created by second-home owners.

Although the contexts and characters are different, separated by no fewer than 2,000 years, when read alongside Virgil’s text, I find it difficult not to hear the themes of Eclogue 1 resonating in Jim Causley’s raw and matter-of-fact lyrics. ‘Stuck-up townsfolk’ equate to the impius miles, while locals forced from their Devonian homeland replace goatherds forced from the Roman patria. Like Virgil, Causley disrupts the straight-forward notion of pastoral idyll, re-focussing the listener on the experience of local people driven out of their homeland by forces beyond their immediate control.

On first reading, many readers struggle to see through the charming poetics of Virgil’s verses and fail to identify the undertones of civil strife. Similarly, Jim Causley’s warm voice, light-hearted style, and West Country inflections wash over a listener in such a disarmingly pleasant way that it is possible to miss the gravity of the song's subject matter on a first listen:

In this village I feel like a stranger

Though I’ve lived here some years before you

And to feel an outsider in the new place

Oh but what’s a simple country boy to do?

Challenging the 'Pastoral’ Vision

The countryside has always existed as much in our imagination as it does in reality. An orchard, a basket of foraged apples, or a thatched cottage roof are what we might wish to envisage, and we might be shocked when we are confronted instead with ‘hobos’, ‘shabby chic’ (Jim Causley), homeless migrants, and dead goat kids (Virgil).

The parallels are only dulled by my written analysis, so I hope you will reflect on them by enjoying Virgil in the English (or Latin), listening to Jim’s beautiful song, and then perhaps enduring my own rendition.

Postscript

After I finished writing this piece, I received a most remarkable insight from Jim himself. Having written to Jim to share with him a draft, Jim replied, informing me that his forthcoming album would be entitled ‘Georgic’ - an allusion to Virgil no less!

We agreed that it was an auspicious sign.

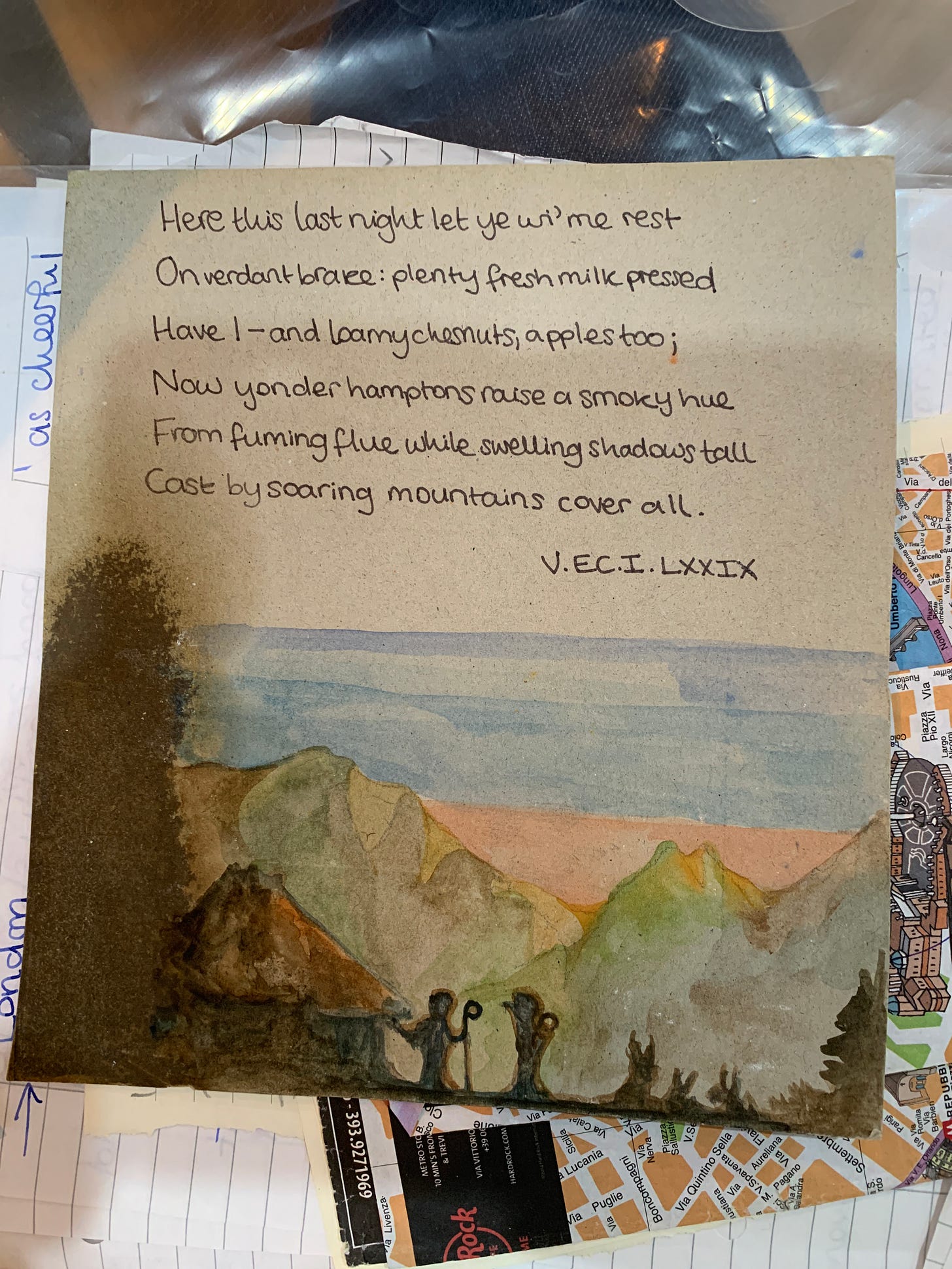

‘Beneath the Beech Tree’

A Translation of Eclogue I (Full Text), Nick Maini

Do we all have somewhere we belong to?

Somewhere to tell folks we’re from?

And besides being a resident of this bouncy blue ball,

Which myth do we base our story on?

You lie ‘neath the shade of a beech tree,

Singing songs on your reed to the Muse.

But my lambs and my flocks are now homeless,

Tell me what’s a simple country boy to do?

Rest here this evening, on the green leafage,

Under my poor cottage roof.

Shadows grow longer, memories grow fonder -

Home!

Some impious soldier will come here,

Till the lands that our forefathers knew.

To barbarians these crops, stuck-up townsfolk replacing

Old characters who’ll never return.

Friend, that city called Rome was my saviour,

And a lad, scarce older than you.

He bade me to graze here my oxen,

To sleep by the stream in the ‘noon.

To the borders of empire I’ll wander,

Never knowing what place I’ll fall on.

Uprooted and secluded,

To Britain or Scythia I’ll go.

So I fear for the next generation,

It’s an old-fashioned country concern.

But tonight you’ve a place in my cottage,

Pressed cheese and ripe apples in turn.

Rest here this evening, on the green leafage,

Under my poor cottage roof.

Shadows grow longer, memories grow fonder -

Home! Home.

Bibliography

The genesis of the analysis of Eclogue 1 summarised here came from conversations with Mr Simon May, the Head of Classics at St Paul’s School. The bulk of the research was informed by an essay that I produced for Professors Tim Whitmarsh and Emily Gowers of St John’s College, Cambridge. That essay referenced the following scholarship:

Clausen, W. (1994): ‘A Commentary on Virgil Eclogues’

Hubbard, T. K. (2008): ‘Allusive Artistry and Vergil’s Revisionary Program: Eclogues 1-3’ , in ‘Oxford Readings in Classical Studies: Vergil's Eclogues’ pp.79-109, edited by Volk, K.

Subsequently, I enjoyed reading these pieces on related topics:

Hymans, S. (2021): ‘Virgil’s first Eclogue: No Idyll’ in Antigone

University of Amsterdam (2020) ‘Our dreams of a perfect countryside blind us to rural reality’

Finally, related and perhaps of interest to some readers, classical manuscripts of Virgil can be viewed in full microscopic detail from the collection of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana at the following links:

Vergilius Romanus (Vat. Lat. 3867), Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, circa 450 CE.

Vergilius Vaticanus (Vat. Lat. 3225), Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, circa 380 CE

Vergilius Augusteus (Vat. Lat. 3256), Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, circa 350 CE