This piece was originally written in May 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic. It was later published in The Cambridge Review of Books.

On the occasion of my grandmother’s 98th birthday, I have decided to re-share the piece here.

To have been able to converse at length with a long-lived grandparent at an adult age has been a unique privilege, all the more so given that my Oma is such a loving and kind woman who has played an important role in shaping my own life.

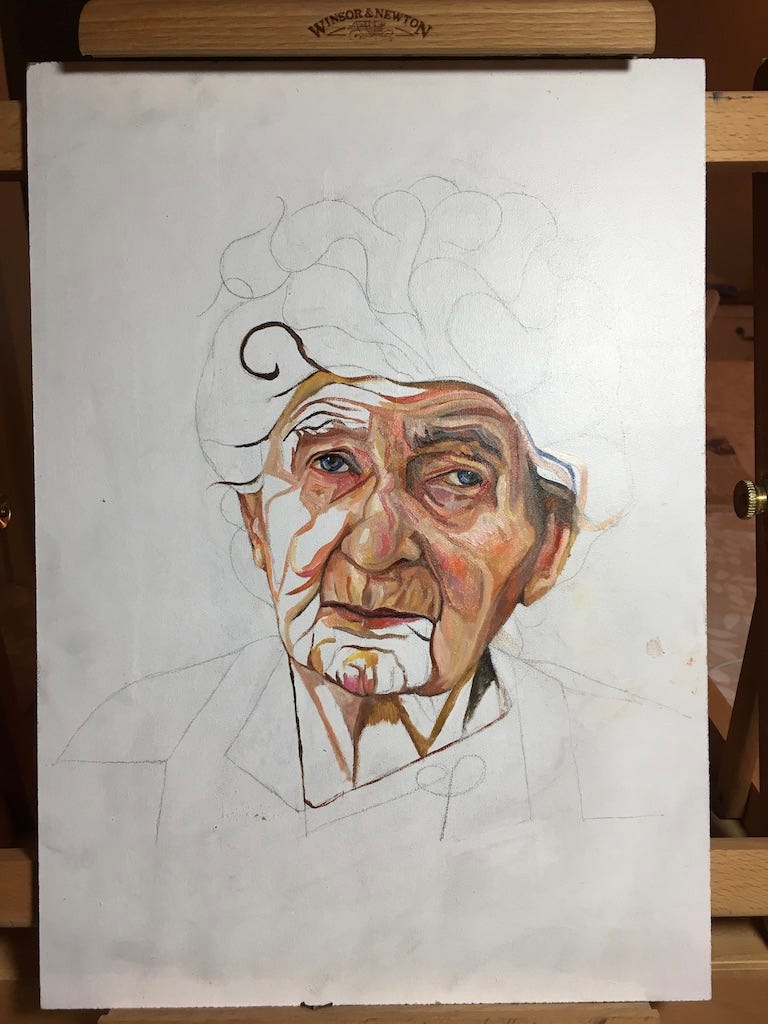

Please enjoy the following account of a series of portraiture sessions and our conversations in the garden:

London, United Kingdom, 2020

Oma leans forward, her hands clasped over the head of the walking-stick. The hornbeams cast a shade from above, a warm green light. She rests, breathing deeply in the still air.

From the undergrowth, a medley of trills erupt.

The melody culminates in a sharp chirp and the identity of the singer is confirmed by a rapid flash of crimson and yellow as a delicate songbird skips out from beneath the bushes. It flits from hedgerow to hedgerow and rustles through the sun-drenched leaves.

Oma’s expression is unchanged and her body perfectly still, but her eyes dart eagerly as they pursue the activities of the garden’s visitor. At last, the goldfinch lands on a branch above her head, coming to a rest.

There is silence again and a gentle breeze brushes past. Then, another surge of activity. Three more songbirds, companions of the first, flit through the foliage; a charm of goldfinches.

Ornithological collective nouns are often redundant: the solitary owl is rarely seen in a pair, let alone in a parliament. Goldfinches, however, do roam collectively and ‘charm’ is fittingly descriptive of their enchanting and colourful appearance.

Oma’s slight movements have reconfigured the way in which the light falls on her face.

The sockets of her eyes, previously shaded, are now lit up. Conversely, new shadows are cast around her jaw where the mandible looms over the neck. What had been mid-tones across the upper planes of her face have been replaced by a brightness which extends from the arches of her cheekbones and along the bridge of her nose.

Extending my arm with a paintbrush held upright, I seize this opportunity to make new observations and take measurements. These gentle head movements have revealed valuable new insights into her facial structure.

I squint and measure by gliding my thumb along the veneered handle of the paint-brush. First, the relationship between the nose and the eyes, then the horizontal distance between the cheeks relative to the vertical length of the head. I transfer my observations onto the board in faint brushstrokes, finally locating where the eyes will sit on the canvas.

It seems to me that the panoramic view of a sitter that is available when painting from life offers an artist an unique set of visual information. Photography, by contrast, presents only specific perspectives on a sitter. A photograph can, for instance, capture an image at a far more granular resolution than any human eye. Likewise, editing software can enable us to adjust the spectral and tonal ranges of an image. Yet, photography still lacks some of the visual information needed to inform a painted portrait. The camera lens flattens its subject and the very precision of the photographic image misleadingly suggests that there is a singular, definitive version of reality. On the other hand, a subject observed in the flesh possesses an ever-shifting dimensionality.

In my view, in-person observation remains the most coherent and complete way to understand how a sitter inhabits space and time, although it can be further enhanced by the aid of photography.

Memories of Italy

The German word, Oma, meaning grandmother, is the affectionate name that our family has always used to address my hyper-alert and inquisitive sitter.

At 94 years old, Oma’s mental and physical agility is still awe-inspiring. Highly active, she owned a speedboat until just over a decade ago, relinquishing it reluctantly, and, until this year, she swam every morning.

More recently, as Oma’s pace of life has slowed, she has begun to use a walking stick. Once a skilled mountain-climber, today climbing stairs requires great exertion. Yet Oma’s mind remains a hive of activity; she occupies her spare time with endless crosswords and, a polyglot, she still uses three or four of her languages each week.

The present portrait sitting is taking place in our family home in a leafy suburb of south-west London, encircled by the meandering Thames. Our patch of garden is modest, but its varied flora attracts a constant flow of wildlife that entertains Oma as we bask in the warm sunlight.

On this occasion, besides the goldfinch display, garden guests comprise a robin, whose whistle begins with piercing clarity before dwindling into silvery twitter, a haggard fox, who brushes gingerly through the vegetation, and the wood-pigeons, whose unrelenting cooing verges on monotony.

Wood-pigeons are a more handsome member of the dove and pigeon family than their urban counterparts, the descendants of rock doves, variously known as ‘feral pigeons’ or ‘city doves’, depending on the disposition one has towards their presence. But wood-pigeons are far less elegant (and far more corpulent) than their other cousins, the turtledoves. Oma takes no strong view on their appearance, but is perplexed by the unresolved structure of their call:

‘They always stop halfway through the song!’

I nod in agreement. Whilst the whistle of the blackbird is euphonious and varied, the wood-pigeon’s murmur is repetitive, bordering on intrusive.

In the background, the two family cats slink into and out of the house. Often they lounge on the shed roof, occasionally they leap over the fence to explore neighbouring plots, but they never seem to their attention towards the pigeons.

‘What did Anna have to say earlier, Oma?’

Each Sunday, at 11:00am, Oma rings her oldest friend, Anna Cappuccino. Anna is a lady of the exact same age as Oma, almost to the day. They have known each other since 1933 when they met in Bologna aged 7. Almost a century later, they still exchange weekly updates in bubbling, excitable Italian.

Anna, now deprived of her eyesight, has moved to near Lake Cuomo where she lives with her daughter’s family and is frequently visited by an extensive progeny. The Cappuccinos seem almost absurdly stereotypical in being such a large and ebullient Italian family.

In the last few months, however, the continuous stream of visitors to Anna in Lake Como have come to a halt. At the outbreak of the pandemic, Italy was first European nation to experience a deadly wave of coronavirus. As the healthcare system in the northern regions was overwhelmed by surging numbers of cases, the country went into a strict lockdown. Now Anna keeps in touch with her family over the phone.

The customary pattern of life has changed for Oma too. Ordinarily, Oma lives by the Thames, near Tower Bridge in Bermondsey. But while the disruption from the pandemic is ongoing, Oma has re-located to live with us to weather out the storm. That means that I am fortunate enough to enjoy a silver lining despite the ongoing crisis. For, at a time when I should have been cramming for university finals amidst the dusty shelves of a Cambridge college library, I have instead been able to spend an unprecedented length of time with my grandmother, as our family has been brought closer together at home.

‘Anna is well! She spoke with your sister too.’

As Oma recounts that day’s exchange with Anna, the direction of our conversation rambles seamlessly from the present into the past. The warmth of Italian custom that Oma enjoys each week when exchanging updates with Anna reminds her of the kindness she experienced as a child living in Bologna.

An assortment of memories of everyday life resurface as Oma paints a picture of Bologna in the early twentieth century. The vignettes are framed by perpetual sunshine, incomparable cuisine, and evenings spent on rooftops. Character sketches of neighbouring children, parochial artisans, and local eccentrics further enhance the emerging tapestry of life. One particularly vivid memory concerns the brief acquisition of a puppy from a nearby farmyard, whose subsequent loss is still a point of anguish for Oma.

These varied recollections are cherished fondly. From time to time, however, they touch on a less rose-tinted reality:

‘Yes, I remember that particular family very clearly. They were lovely people and the parents were wonderful. The father, especially, was an entertaining and kind man. And, of course, when they banned Italians from talking to Jews, he did not comply. He still came over to greet us and would throw me in the air!’

Oma’s family life in Bologna was not the result of voluntary emigration, but a necessary flight from the seething currents of the twentieth century’s turmoil.

Munich, Weimar Republic, 1926

Born in 1926 to an affluent family and raised in a suburb of Munich, fair-haired and bright-eyed, Oma was by all appearances a typical Bavarian girl and she did not stick out as ‘a Jew’. This is not particularly surprising given that Oma’s maternal ancestors had lived in the German-speaking territories and principalities for centuries, long before the confederation and unification of Germany was ever achieved.

Similarly, Oma’s paternal Jewish forebears arrived in the central European states some centuries before the Austro-Hungarian Empire was formed and outlived its demise. The Furstenheims, the Uiberhals, the Cohns, and the Worms were all families with culturally Jewish roots, but they were also deeply assimilated into their local culture, flourishing within their respective communities.

This assimilation is perhaps most clearly illustrated by the fact that, when, at the outbreak of war in 1914, their states called upon them, Oma’s male relatives re-joined their former military regiments and marched off to far-flung battlefields.

Six uncles were awarded Iron Crosses for services on the Western or Eastern Fronts: some fought in Flanders and bore witness to the carnage of Verdun; one flew aeroplanes for the nascent air-force; others froze in the snow-cloaked wastes of Galicia and the Carpathians; one, operating undercover in the Arabian Peninsula, disappeared in mysterious circumstances, purportedly murdered by desert tribesmen; and another, a tall, handsome officer, was killed by a sniper upon returning to his hometown following the collapse of Austro-Hungary, a week after armistice had been declared and war had supposedly ended.

By the 1920s, Oma’s family had begun to disengage with Jewish cultural traditions. Most had become more or less atheistic, while some had even embraced Catholic or Protestant Christian practices.

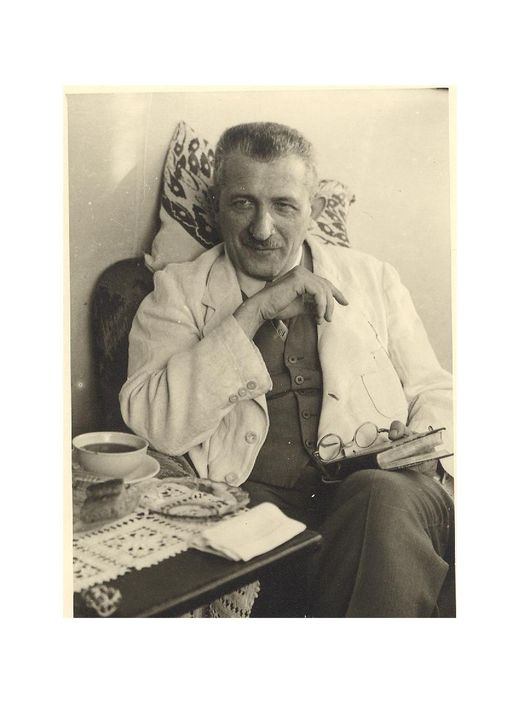

Oma’s parents, in particular, were thoroughly assimilated. Her father, Ludwig, was educated at the foremost German university, Heidelberg, and later acquired a post-doctorate degree in Vienna. Subsequently, he achieved notability as a scholar of Goethe. In his spare time, he wrote satirical pieces for local newspapers that found humour in the foibles of everyday Bavarian life. Her mother, Hertha, was a well-educated lady who spent some years working in Berlin before meeting Ludwig. An early adopter of skiing, she loved to take the family up into the Bavarian mountains for holidays.

But what follows is, of course, an all-too familiar story. In the wake of the First World War, extreme political doctrines ran riot as communism and fascism swept through populations ripe for radicalisation. In Germany, the ascendant ‘Nazi’ regime unleashed an expansionist programme of racial ideology. Ultimately, their populist policies, demands for Lebensraum, and eugenicist agenda precipitated warfare on a global scale as well as a genocide of an almost unprecedented magnitude.

In the 1930s, Oma recalls how her school class was summoned to join a political rally in her hometown of Munich, also the birthplace of National Socialism. Oma herself presented as such a typical ‘German’ child that her anti-fascist teacher was able to place her at the front of the parade, right beneath of the eyes of an unsuspecting the Nazi high command.

Witnessing Nazism at its very source in Munich, it soon became evident to Oma’s parents that their family life in Munich was no longer tenable. In 1933, the situation became such that Oma’s family decided to leave Germany altogether and relocate to Italy. They arrived in Bologna via Florence, two university cities where her father had friends and academic connections.

Despite the move, Oma kept in touch with her activist teacher in Munich, Fraulein Köberle, who in turn forwarded letters from her classmates to Bologna. Oma’s replies, supplemented with parcels of Italian culinary delights, were distributed among the class.

Aged just 7 and largely unaware of the seriousness of the developing political situation, Oma’s memories of Munich, like those of Bologna, are almost uniformly fond: games in the local park between the apartment blocks; young boys with slingshots; skiing during the school holidays. She firmly reminds me:

‘Not all Germans were Nazis, not all Italians were fascists.’

But, of course, enough were.

Notes on Florentine Ateliers

The sitting, which had begun in silence, gradually blossoms into conversation.

For me, the aim of painting a portrait is not simply to produce an accurate visual representation, a likeness, of your subject, but also to build a more complete picture of the psychology of your sitter. Often the flow of the conversation corresponds to the flow of the paint on the palette.

For this portrait, I elected to work in oil paint on medium density fibre-board (MDF) that I had primed with a layer of white gesso. Unlike canvas, whose springy cotton undulations can inhibit brushwork, the less textured surface of MDF picks up paint in a more uniform manner.

I find that the immaculate whiteness of a blank canvas can distort the eye’s ability to perceive colour, so I begin my process by neutralising the colour-blinding effects of the board’s white surface with a layer of neutral, ochre-coloured ground.

Typically, as I sketch out the initial measurements of a picture, I first decide on the portrait’s framing, then the composition of the figure as well as the manner of lighting. After that, I can gradually begin to build up the architecture of the face.

At its most strict, my palette only holds five colours: lead white, yellow ochre, burnt sienna, ivory black, and ultramarine blue. This restricted palette is a consequence of a summer spent in Florence studying the methodologies and materials of traditional Florentine ateliers.

These art studios trace their genealogy back through art history to the workshops of Titian, Van Dyck and Velasquez, and pride themselves on preserving for posterity the portraiture techniques that originated in the Italian and Dutch Renaissances. These methods were later enhanced by the society artists of eighteenth century Britain like Gainsborough, Romney, Raeburn, and achieved an unrivalled zenith in the hands of Victorian master-draughtsmen such as John Singer Sargent and Phillip de László in the twilight of the nineteenth century.

Amongst the Florentine ateliers, the ability to produce oil paints, varnishes, and thinners that resemble those used by their revered forebears is a prized craft. In pursuit of that aim, each atelier has developed their own quasi-necromantic practices and arcane recipes (often based more on trial-and-error than on textual sources). Even where original ingredients can be ascertained through textual interrogation, the methods of grinding and mixing are often disputed.

The ingredients themselves can also be difficult to acquire. Burnt sienna, for instance, comes from natural earth pigments from the Siena region in Italy, while ultramarine blue is produced using lapis lazuli from mines in Afghanistan.

Substances used as dilutants for oil paints are similarly esoteric. Typically, the mixer is either: spirit of turpentine (the distillation of resin harvested from pine trees); white spirit (also known as mineral turpentine, the synthetic equivalent of natural turps); or linseed oil (a viscous liquid, pressed from the dried, ripened seeds of flax plants).

These dilutants are invariably pungent, often nauseatingly so, creating the distinctive musk that clings to the rafters of Florentine art studios.

More remarkable still is the fact that these substances are toxic in nature. Long-term exposure to them has proved debilitating or even lethal to many an acolyte of portraiture. Extensive exposure to cadmium may result in a phenomenon referred to as the ‘cadmium blues’, with flu-like symptoms including chills, fever, and muscle ache. Meanwhile, the milder side effects of lead poisoning include vomiting to which I can personally attest following a bungled attempt at grinding the pigment into powder at a studio in the Piazzale Donatello.

Why would any artist bother with such toxic substances? I suppose, in the case of lead white, the paint’s heavy body, when mixed in a certain manner, creates skin tones than are unsurpassed by any other material. Cadmium red, another studio favourite, produces a hue of red whose vibrancy is unrivalled. But mostly, the persistence of these materials derives from a hankering for tradition and lost artistic knowledge on the part of some practitioners, to which I only subscribe in a half-hearted sort of way.

Mercifully, the modern era has heralded the arrival of non-lethal (and more environmentally friendly) substitutes for these essential art supplies that, in my view, are largely successful in imitating the traditional materials.

The Art of People-Watching

As our conversation courses onwards, Oma and I are unexpectedly interrupted by a scratching sound emanating from the foliage that cloaks the fence.

Turning, we see a child’s head peering cautiously out over the wooden lattice of the garden-fence, promptly followed by a second. Delighted, the children stare out in fascination at Oma. She, equally intrigued, peers back, before breaking into a smile and waving hello. This provokes a burst of excited giggling from the children who scramble back into the cover of the neighbouring garden’s bushes.

A self-confessed people watcher, Oma is fascinated by gaze and is indiscriminate in her practice of the art of observation.

In the context of our portrait sitting, as the painter, I am supposedly the observer, while Oma, the sitter, is the observed. Over the course of the sitting, however, I often sense that the roles are reversed.

Oma squints at me unremittingly, frequently tilting her head to get a better view. Posture and enunciation are the foremost targets of her critique as Oma intently observes my demeanour, offering an occasional commentary on the quality of my posture and the clarity of my diction.

Likewise, whenever I have recourse to use ‘technology’ (her censorious label for phones, laptops, and other hardware), Oma demands a full explanation of each machine’s inner-workings. Invariably, her lines of questioning rapidly breach the limits of any technical expertise that I might pretend to have.

As our conversation progresses, she shares some advice that perhaps hint at the deeper-seated origins of her observational habit:

‘My father told me: “Always take an interest in and revere those who you come into contact with, regardless of their background.”’

Eventually, Oma’s family situation in Mussolini’s Italy became as untenable as it had been in Hitler’s Germany. Her father’s closest academic colleague, Professor Bianchi, was co-opted into the Italian Fascist regime in his capacity at the University of Bologna. Oma recalls seeing Bianchi, sat sullenly in a black uniform at the local stadium in Bologna during a political rally. As in Munich, her school class had been compelled to attend the rally and she was taken along with them.

When new laws were passed prohibiting social interactions with Jews, a few neighbours began to shun the family. This appalled Anna Cappuccino, who took her brothers to reprimand a neighbour who refused to acknowledge or even look at Oma’s family in the street. The final straw was the passing of laws banning all foreign Jews from residence in Italy.

Thereafter, it would be illegal for them to remain.

Vienna, Austria, 1908

From the conservatory indoors, the light tones of my sister’s voice glide through the air.

She is sat at the piano, singing warm up scales before tuning her harp. The sound of the notes transport Oma back through time to the sitting room of an apartment in Vienna where her aunt, Henryka, taught piano lessons.

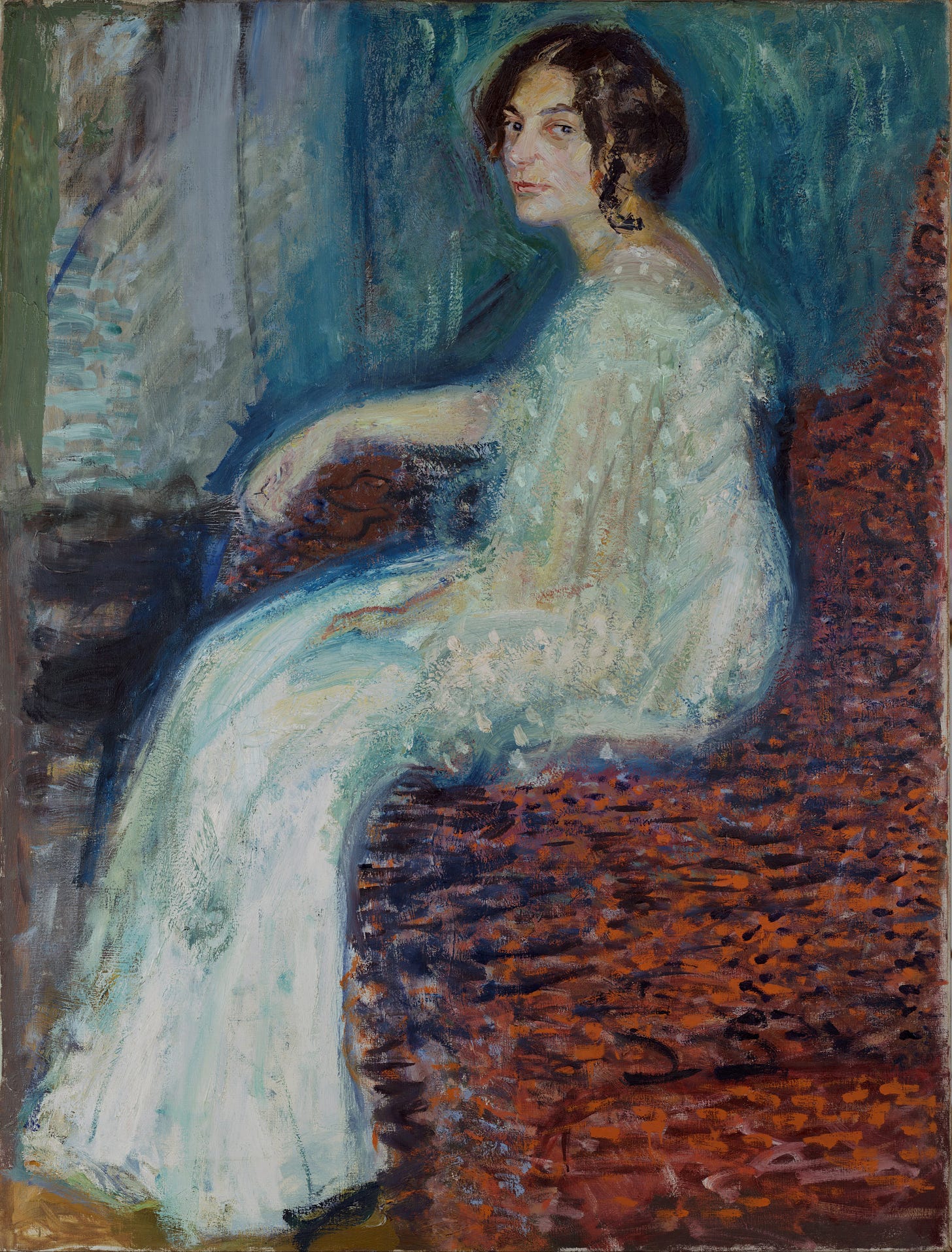

If you ever visit Vienna’s Leopold Museum and enter at the main entrance, near where Mariahilferstrasse meets the Ringstrasse at the Museumplatz, one of the first large portraits that will come into sight is of this same aunt; Henryka Cohn. The portrait, a centrepiece of an art movement which rejected the style of the Viennese Secession, was produced by the erstwhile painter, Richard Gerstl.

Gerstl was the archetype of the tormented artist with an ego to match.

While studying at the Viennese Academy of Fine Arts, he is reported to have shouted at Christian Griepenkerl, a widely respected professor, the following taunt:

So wie Sie malen, kann ich in den Schnee brunzen!

I can piss in the snow better than you can paint!

Gerstl quickly gained a reputation for being psychologically unstable, impulsive, and radical. When his affair with the wife of a friend fell apart, Gerstl entered a characteristic frenzy.

On a cold November night in 1908, distraught and isolated, Gerstl retired to his studio and gathered together all the artworks, letters and personal papers on which he could lay his hands. Then, setting the bonfire alight, he hung himself from the rafters in front of the studio mirror. The autopsy sardonically notes that he also managed to stab himself.

That is how, along with almost the entirety of his artistic oeuvre, Gerstl passed into oblivion, aged just 25. Henryka’s portrait, meanwhile, by virtue of the fact that it was hung in the family apartment, evaded Gerstl’s ruinous fate.

Yet, despite surviving Gerstl’s death, the painting did not remain safely in the apartment for long.

When I mention Gerstl to Oma, she reminds me of a similarly tragic event. Henryka’s sister, Hansi, had died suddenly of an infection, causing a young Austrian officer who had been infatuated with her to commit suicide in despair. A photograph of Hansi still hangs in the frame above Oma’s bed.

My father leans over at this point to expand on the details of Henryka’s life. He relates that she was a vibrant character, a proto-vegan and yoga enthusiast, who advocated for women’s rights and female education. My other sister, who has been reading a book nearby and who is a long-time practitioner of vegan-ism, is particularly delighted by these details.

Vienna, Austria, 1938

In February 1938, before leaving Bologna for the final time, Oma’s family paid one last visit to her father’s relatives in Vienna.

Oma relates to me details of the train journey from Italy to Austria, reminiscing about particular stop-offs, hotels and meals. But other, less convivial memories also return:

For the first time on that journey I felt very frightened.

Fahrkarten! the guards would shout as they came by in their uniforms to stamp the tickets.

I shall not forget that feeling of being afraid - afraid that at any moment they might seize our luggage, or us.

The Vienna visit was meant to be brief, but when Oma’s father contracted pneumonia, the family had to delay their return, awaiting his recovery.

Oma recalls spending pleasant afternoons skating on the local ice-rink during that period. But it was a close call. Just weeks after their departure, Anschluss was declared as the Third Reich annexed Austria on 12 March 1938.

Then, the ‘Aryanisation’ of Jewish property began; namely, the systematic expropriation and murder of the Austrian Jews. Adolf Eichmann was dispatched by the Nazi Party to oversee the Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung in Wien (The Central Agency for Jewish Emigration in Vienna). Henryka, like all of Oma’s family and millions of other European Jews, had her entire estate expropriated, all her property and assets, everything from apartments to businesses, paintings, furniture, manuscripts, and musical instruments. Indeed, the wealth extracted during this period was so enormous that it formed the financial bedrock for the Nazis war effort.

In May 1939, Henryka, sensing the gravity of the situation, weighed up her options. Evidently, she determined that personal safety was more valuable than material possessions. Having made friends during travels in Great Britain during the 1920s, she was incredibly fortunate that two of those families, the Abbotts and the Gardiners, were willing to serve as her sponsors. As soon as she could, Henryka fled Austria and arrived in London with almost no personal possessions save for the clothes on her back. That is how she escaped the Holocaust.

The rest of the family was less fortunate. Henryka’s brother Richard and his wife Ilse, for instance, with whom Oma’s family had stayed while in Vienna, sought the right to emigrate to Australia but were refused at the embassy. They perished a few months later in disease-ridden concentration camps.

Another member of the family was Ernst Flatow (one of the aforementioned Iron Cross holders, who had been recognised for acts at Verdun). Having converted to Christianity, Ernst became a celebrated priest in his local community. Despite being presented with the opportunity to leave Germany, Flatow chose to remain with his church and congregation. Subsequently, Church authorities, in collaboration with the Nazi regime, identified him as a Jew and deported him to the Warsaw Ghetto, where he died as a forced labourer.

That is how so many of the family were murdered, once their possessions had been expropriated, they were forced out of their communities into ghettos and then camps.

As for The Portrait of Henryka Cohn, Oma recalls seeing it on the occasions when the family visited Vienna. Indeed, if you inspect the reverse of the canvas, as one scholar notes, you will find Henryka’s handwriting, recording her name and address. The Museum, however, claims that, “the picture was never owned by the Cohn family and was found as part of the artist’s estate.” To date, no sources have been produced to validate these claims.

Today, Henryka’s portrait still hangs in Vienna, the city of its birth. There it can be appreciated by all. Appreciated by all that is, if all are willing to pay the Leopold Museum’s €20 entrance fee…

Windhoek, German South-West Africa, 1939

Following their narrow escape from Vienna, Oma’s parents resolved to leave Europe altogether.

Initial enquiries were sent by her father to friends in the United States. There was a relative who had recently moved to an emerging Jewish state in the Middle East, but fresh legislation had restricted Jewish migration to this area of Palestine. The sheer flood of those fleeing violent persecution across Eurasia, from Russia to France, had become unmanageable.

Their deliverance came instead in the form of her mother’s uncle, Erich, who had emigrated many years earlier from Berlin to a colonial outpost in German south-west Africa, modern-day Namibia.

Erich had emigrated to the German colony to establish a diamond mine where he planned make his fortune, which he duly did. As Oma notes, however, Erich’s enterprise may have been prompted less by his thirst for adventure and more by his expensive vices. She grins as she recalls the man:

‘A drinker and a gambler!’

In January 1939, the family left Italy for Namibia. Having experienced social alienation and the hostility of neighbours in Munich, Bologna, and Vienna, Oma’s family was shocked to observe the way in which black Africans were treated by settlers in Windhoek. Oma recalls gloomily:

‘My mother and father interacted with the people who did serving jobs differently to the way in which my friends parents treated them. They treated them with respect and took an interest in their lives.’

Cape Town, British South Africa, 1940

We pause while Oma takes her afternoon tea.

Gazing into the distance, my eye is caught by a sculpture in the undergrowth and I am reminded that Oma too has played the role of the artist.

For some years, Oma was an amateur sculptor. Her sculptures and pottery line the walls of her apartment as well as the homes of many family and friends. The object that has jolted my memory is one of these sculptures, titled, Siren, it is an arresting, turquoise-green figure that now sits in the undergrowth of our garden. Oma’s sculptures are often sprawling figures, whose limbs and clothes are an abstract mass of drapes and folds that turn heavy inert material into intelligible forms nestled within swirls and spirals.

For Oma, it seems to me that the steady intensity of her gaze is equalising. Persistent observation facilitates understanding and tolerance, while refusal to engage has damaging consequences.

Many hours spent haunting life drawing sessions have taught me the same lesson. Regardless of how you may have felt about the model’s body when it was first unveiled in all its naked glory, by the time you depart two hours later, they will have become intriguing and beautiful. Whether obese, emaciated, scarred, or wrinkled, after sustained scrutiny every body becomes uniquely attractive and fascinating.

I noticed this phenomenon in its most extreme form whilst studying the disfigured faces of early facial reconstructive surgery patients, the victims of the First World War’s industrialised warfare. At first, these men’s visceral facial wounds were difficult to look at. And yet, after spending many hours observing, drawing and painting them, they became not just ordinary, but even fascinating and beautiful.

Following a their stop-off with Erich in Namibia where many German settlers still had strong affiliations with the Nazi party, the family decided to move once more, this time to British South Africa.

In Cape Town, Oma once again had to adapt quickly to her altered circumstances. At school, she learnt two more languages, English and Afrikaans, in addition to the German and Italian she already knew.

‘When you're a child, you learn fast because you want to fit in – you pick up the mannerisms and the accent.

After just a month I recited Wordsworth’s daffodils poem in front of the entire school.’

The reference to Wordsworth’s I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud is a jarring reminder of the life that the pandemic has disrupted. Wordsworth was an undergraduate at St John’s in Cambridge, the place that I should be studying at this moment in time.

At this time of year, I think to myself, the daffodils would be in full bloom in the wildflower meadows on the banks of the River Cam.

Eyes & Wrinkles

Oma’s face is beginning to emerge from the board’s surface.

I work from the darks to the lights, adding in half-tones as I progress. After the main forms are blocked in, I start work on the detail. When a steadier hand is required, I rest my brush on a mahl-stick. When broader, more dynamic brushstrokes are in order, I alternate between standing up, sitting down, striding towards the easel, then backing away again. These movements help me as I attempt to gauge the accuracy of the portrait’s likeness, revealing the proportional discrepancies between life and art.

Protracted periods spent staring at the painting close up can cause a sort of blindness, an inability to see the wood from the trees and the overall likeness can be lost as you are drawn too far into specific details.

There is an anecdote preserved by a contemporary biographer of Gainsborough who records that the artist’s most cherished paintbrush had a six-foot handle. Other techniques seek the same end. You may sometimes see artists with their backs to their subject, holding a mirror. It sounds counterintuitive, but the method is sound – an inverted reflection often highlights proportional inaccuracies in a portrait.

‘I am going to need you to look over here for a moment and sit rather still for a few minutes, Oma.’

I prepare to tackle the part of the portrait which is perhaps the most important of all - the eyes.

Intuitively, when inspecting a portrait, the viewer’s eyes are drawn to the eyes of the painting. This may be because eyes form an important part of recognition and emotional communication in social interactions. For this reason, a pair of eyes can make or break a portrait.

Personally, I find each element of the eye deeply satisfying to paint: the swimming, cloudy colours of the iris; the milky whites of the eyes; the glistening rims of the eyelids and the fold of skin in the corner (apparently known as the ‘lacrimal caruncle’); the shadow cast by the eyelashes; and, most importantly of all, the gleam of light in the pupil.

In Oma’s case, the precise colour of her eyes is a point of contention. My sister reckons them to be blue, but my father argues for a sort of green hue, while I maintain that they are more of a blue-grey colour. Oma, for her part, reckons that their colour may even have changed somewhat over the years.

Skin, on the other hand, which covers most of the face, does not stand out in quite the same way and is frequently the most frustrating part of a portrait, depending on whether the face is young or elderly. The smooth, tautness of young skin is completely different to the myriad of crisscrossing wrinkles on older weathered skin.

Catching a glimpse of the portrait, Oma exclaims:

‘Just wrinkles! My goodness, I look in the mirror and that’s all I see – a little old lady staring back.’

London, United Kingdom, 1946

Since it is seventy-fifth anniversary of Victory in Europe Day, my mother has furnished the house with a bunting of Union Jack flags.

I ask Oma whether she remembers where she was on 8 May 1945. Her memory of that day, as of much of the Second World War, is indistinct.

Living in Cape Town, so far from the main theatres of conflict, one of her strongest memories of 1939-45 is of knitting socks for the troops. But her recollections of the post-war period are illuminating.

In 1946, soon after the war and aged 20, Oma emigrated from South Africa to Britain. At the University of Cape Town, she and several friends had been appalled by apartheid South Africa. A few of them had decided that they no longer wished to remain there.

Oddly enough, when Oma first arrived in London, her first residence was just two roads over from where are currently sat.

Oma recalls the particular phenomena that marked out that era: smog, so thick that in the daytime you could not see the street in front of you and being guided by the dim glimmer of lamp-posts; cycling on clear days down Whitehall through streets devoid of cars; and rationing with the accompanying strictures of a rationed diet.

Unlike Cape Town, London had been severely affected by the war. The docklands had been razed to the ground, while ancient monuments and archives had been destroyed in fires. For decades afterwards, the rows of suburban terraced houses were punctuated by bomb-sites.

As Oma talks, her voice is slowly drowned out by the roar of an aeroplane engine overhead. Our garden is directly under the Heathrow flight-path and when a plane passes over, its sound deafens any conversation and obliterates the birdsong. During the current pandemic, however, the continuous flow of planes has ceased, and this sort of interruption is a much rarer occurrence.

When the roar subsides, Oma recalls how, in the 1940s, local residents, deeply affected by their experience of the air-raids and the Blitz, would still flinch when they heard the drone of a plane’s engine.

Dreams & Brushstrokes

Throughout the afternoon we have taken regular breaks and we pause for another now. During the pause, Oma casts her eye over an essay I have just completed which discusses the significance of dreams in the Aeneid. Oma approves of it but notes, solemnly:

‘You dream less as you get older. Nights are disrupted and you experience a different sort of sleep – less vivid.’

During this final break, I doodle a face on my palette in wide translucent brushstrokes. A rugged old chap stares back at me from the wooden plate. As we commence the final sitting, I again need the palette space and the face, however splendid, cannot stay.

Wiping the transient figure away with a cloth, I am reminded of a moment from school days. While I was grappling with an almost complete painting but struggling to finish, my art teacher had loomed over my shoulder.

‘May I suggest something?’ said Mr Flint, to which I willingly replied, ‘Why of course, Sir!’

Without further ado, he whipped out a cloth and wiped almost the entire image off the board in one clean stroke. Stunned, it took me a moment to appreciate the point, but his reasoning was sound, and the advice often re-echoes in my head:

‘Don’t get allow yourself to wallow in the details of the piece. Keep it fresh, and if you find you are getting stuck, wipe it away and start again.’

Memory & Remembering

‘What was it we had last night? I wrote it somewhere… Ah here it is!

Blackberry crumble.’

Oma now writes much more to help her remember. Just yesterday, she had described to me how her mother had passed away aged just 50 with advanced Alzheimer’s, barely able to remember her husband.

Oma has so far successfully retained her faculties for nine decades, but just as much as in the twentieth century, forgetfulness and dementia are still hallmarks of old age.

‘It’s strange, if I do not talk about you playing ‘saxophone’ often enough that word goes! A word like that – just gone! It seems to return eventually though.’

But perhaps one day it will not return.

As the daylight begins to fade and the shadows on Oma’s face start to lengthen, I sense that it is almost time for this sitting to draw to a close. A portrait painted in natural daylight cannot be continued under artificial lightning. The effect of the light change on the face is too extreme to sustain continuity. This portrait is complete.

Almost immediately, I form a vision of a further, final portrait of Oma to add to the small collection I have now accumulated.

For all my pontificating on the virtues of painting from life, the final portrait that I produce will have to be from photographs. This is in part due to the fact that I want to change tack and produce a more photo-realistic portrait. The more urgent reason, though, is the fact that Oma will soon be returning home.

When she arrived at ours in early April, she had been very ill, and it was unclear what degree of restriction the government would impose. Now, she has recovered and, as the timeline of the lockdown becomes clearer and restrictions are gradually lifted, the time for her to resume her former mode of life has come.

Etymologically, the word ‘portrait’ comes via French portraire from Latin protrahere – ‘to drag out’. This seems quite fitting.

To produce a portrait is to draw out a likeness by literally dragging materials into a form which communicates the subject. In the case of oil painting, this dragging constitutes rearranging of the grains of pigment and oily fluid in a search for the right combination of hues. In the case of clay sculpting, it is a literal dragging of the earthy material into a recognisable form.

Another semantic shade of protrahere is ‘to bring light to’ or ‘to expose’. This too resonates well with an artistic rendering: the artist applies their individual hand and eye to a subject, bringing to light their particular representation of the subject.

A portrait offers the viewer a record of the artists’ interaction with and experience of the subject. Often portraits unintentionally highlight and bring to light features of a subject, inducing in the viewer new ways of seeing the subject.

I look down at the portrait that I have produced. Then, I look back up at Oma.

Saddened, I feel that I have not captured a sense of her being and have not done justice to my sitter. This is troubles me because I realise that my inadequacies as a draughtsman will be read literally as the honest way in which I perceive Oma.

Hopefully, I shall have more success next time.

The Final Sitting

Over the course of our sittings, the conversation has spanned almost a century of life.

Musing to myself as I pack away the paints and clean the brushes, I wonder to what extent Oma’s experience of the instability and disruption caused by the Second World War shaped her perspective on life. Then I wonder whether our perspective on life will be moulded by the experience of the coronavirus pandemic.

Oma’s comments have infused vivid energy into the carefully researched family history that I have been taught by my father. His is a fountain of genealogical knowledge and he is always at hand to fill the gaps in my understanding of the historical facts. But Oma’s insights into the daily realities of life in the past bestow upon those facts a new three-dimensionality.

My father, retiring from the study, joins us in the garden to read The Spectator nearby and ruminates out loud on some gloomy facet of the pandemic.

Turning to me, Oma very seriously stresses the point:

‘I don’t care two hoots if I get this virus or not! You see, I have reached a stage of life where my perspective is now different. Other people will be anxious, but I am not. I’m prepared.’

As I support Oma up from her chair, our attention is caught one final time by a birdsong.

Gazing upwards, we see a solitary shape climbing into the clear expanse of blue sky above us. It is a skylark, soaring effortlessly into the heavens. As it soars, there is no break in its song, rather a perpetual melody, streaming into the heavens.

Appendix: Further Reading

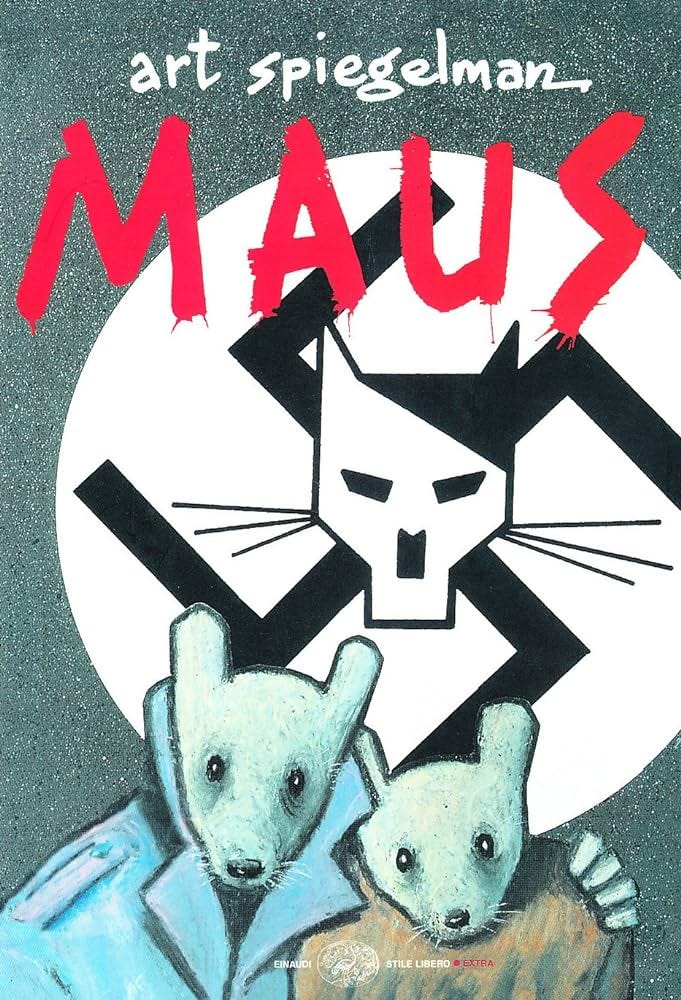

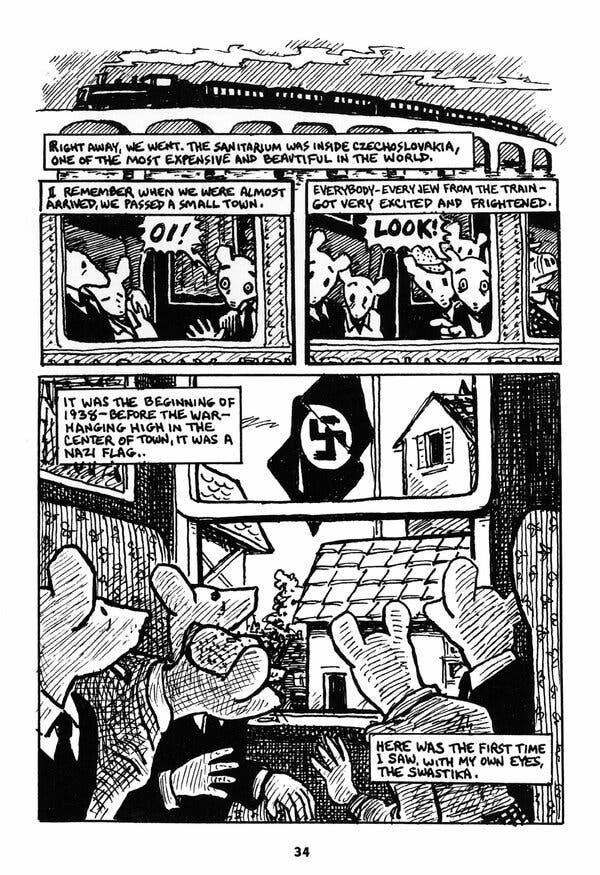

In 2023, several years after writing this piece, I found myself in Paris, at the apartment of a close friend. There, late on evening, he pulled out several of his favourite graphic novels from the bookshelves. He commended to me one book in particular, ‘Maus’ by Art Spiegelman. Knowing his recommendations to be solid, I took the book to bed with me. Some hours later, I finally put it down again having finished reading it that very same night.

Like many texts that relate accounts of the Holocaust, the book is as horrifying as it is all-consuming. What I found particularly spell-binding about Maus, however, was the narrative style. The novel’s narrative takes the form of the author conversing with his father. Over the course of several conversations, Spiegelman learns about his parent’s lives before, during, and after the Second World War. The conversations narrate the past but the narrative flow is frequently interrupted by life in the author’s present day. In reading Spiegelman, I was struck that I had unwittingly chosen a comparable narrative style with which to write this piece.

Maus is a gripping and worthwhile read. Given that this piece touches on the Holocaust, for anyone who wishes to better comprehend the magnitude of that crime against humanity, I would like to take this moment to recommend that book, as well as the following three sources:

BBC Archive, Richard Dimbleby’s Report on Belsen-Bergen Concentration Camp, April 1945 (audio)

The Rest is History, The Man Who Escaped Auschwitz, January 2023 (audio)

The World at War, Genocide, Episode 20, March 1974 (video documentary)