Overview: Writing from a bunk-bed on a container ship crossing the North Sea, I reflected on the complex global systems and the nature of collective knowledge.

Is it possible to travel to the Netherlands without taking a train or plane?

Did Popeye eat spinach because of its iron content?

What is the nature of knowledge in complex systems?

This piece was originally composed in December 2021 and was re-drafted in December 2022. Special thanks to my friends Paul, Lucy, and Quentin for sharing feedback on draft versions.

On Container Ships

Harwich to Holland

The bunk beneath me shook as, deep within the bowels of the ship, four monumental engines began to roar. The distant reverberations made the entire cabin shudder, propelling the vast vessel out of the port and towards the North Sea.

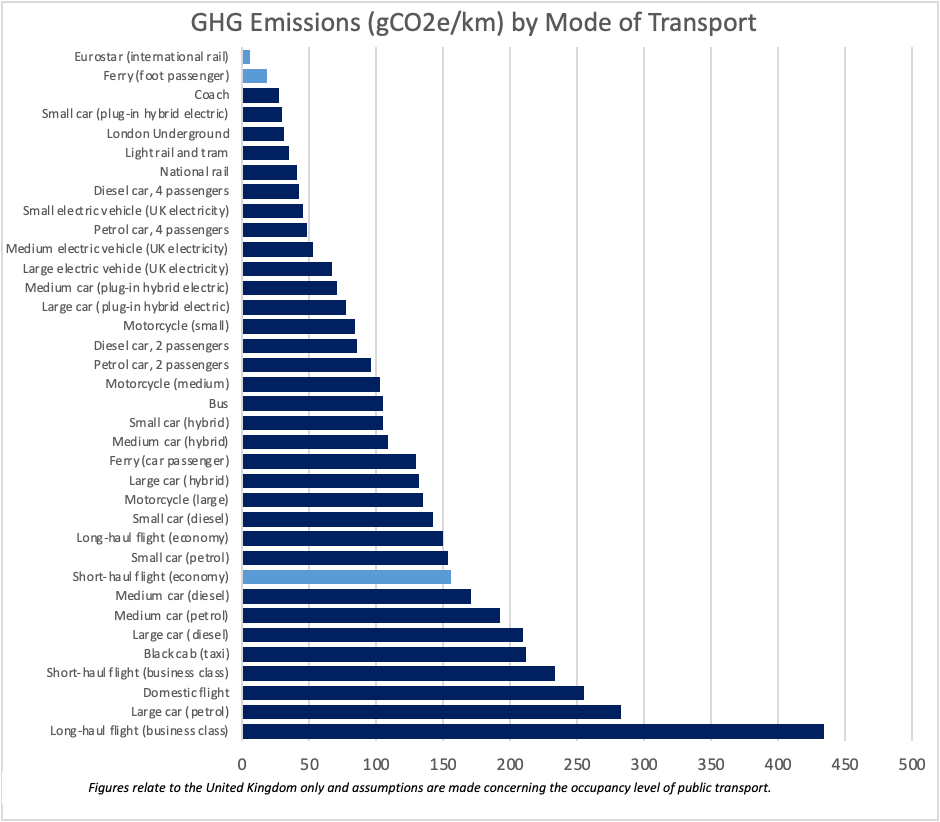

Earlier that day, I had decided to book a last-minute trip to the Netherlands. This was uncharacteristically spontaneous. Searching online, I was not at all surprised to discover that train tickets were sold out, but was disappointed to find that there were dozens of aeroplane flights available at low prices. In fact, the plane was by far the cheapest travel option.

Unwilling to capitulate to this most carbon-intensive form of transport, I searched for another way to make my journey to the Low Countries and came across a further option - the cargo liner.

When business ended that evening, I leapt onto a train that pulled into the station beneath my office. In just over an hour, I was shuttled from the heart of the City of London to a windswept harbour on the East Anglian coast.

There are two ships that chart the route each day from Harwich to the Hoek van Holland, the ‘Hollandica’ and the ‘Britannica’. They are the largest hybrid cargo liners in the world and each transports around 1,000 passengers (mostly hauliers driving HGVs) and a cargo of 62,000 tonnes - hundreds of lorries and containers packed with freight.

San Pedro to Suez

This journey took place in November 2021, during COVID-19 pandemic, between spasms of state-imposed lockdown. Readers may recall how, at that time, the rules around personal freedom changed almost daily.

In 2021, supply chains were on my mind, as they were for many others, so I was delighted that the cargo liner journey would enable me to pass through a major trade centre. This way, I would be able to see first-hand the ways in which the port authorities were dealing with the triple-headed spectre of demand spikes, pandemic restrictions, and Brexit.

Ports, the beating heart of the modern global supply chain, were overwhelmed in 2020 and 2021 by an unparalleled series of supply and demand pressures stoked by the pandemic. On the demand side, pressure was fuelled by consumers who were trapped in their homes and spurred on by direct government payments (in the UK, in the form of the ‘furlough’ Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme). On the supply side, sick workers, empty factories, lost shipping containers, a shortage of longshoremen, as well as years of under-investment in logistical infrastructure resulted in the complete disarray of an already fragile ‘just-in-time’ network of global supply chains.

During this period, average delays at the Port of Los Angeles regularly exceeded 100 days, producing captivating bird’s eye images of the San Pedro Bay awash with container ships. The pressures crescendoed from July to December 2021 and finally peaked in January 2022. Up to the present day, these pressures have now almost entirely subsided (a shortage is invariably followed by a glut).

In March 2021, another maritime shipping scene captivated the world. The Ever Given, a container ship of 220,000 gross tonnage, ran aground in the Suez Canal.

Wedged in between the banks of the canal, the Ever Given not only blocked the narrow causeway (creating a backlog of more than 350 ships), but also disrupted the entire global supply chain. The Ever Given is a powerful visual reminder of the vulnerability of our global network of supply chains.

On Complex Systems

‘Dangling at the end of a supply chain’

Recall that moment of utter confusion in March 2020, right at the start of the pandemic. As the virus swept across the world via unsuspecting bronchioles, our economies shut down overnight and toilet roll disappeared.

It was easy to suspect the worst. Would our supply chains be resilient enough? Would the rule of law endure? Would the armed forces step in? Had the Texan doomsday preppers been right all along?

Recently, by pure accident, I knocked a jar of frankfurters off a shelf in the supermarket. In painful slow motion, I saw the jar fall and shatter, spilling its contents onto the floor. Deeply embarrassed, I swept up fragments ineffectually while a disappointed-looking store assistant fetched a mop.

Crouching in the puddle of brine, I stared up at the shelves. “How cruel,” I thought to myself, “that so much energy and effort had gone into producing this jar of frankfurters, only for it to end up on the floor, my victim.”

The year-round operational and technological complexity required to deliver the frankfurter jar to my local supermarket, along with as many as 30,000 different stock-keeping units, is nothing short of miraculous. But the intricacies of stock-keeping and delivery within the supermarket network are one piece of a far more complex jigsaw.

When considered in the broadest possible scope, the distribution networks, the physical infrastructure, and the economies of scale required to deliver to the supermarket an item as mundane as a jar of frankfurters are vast. Whether that be the process of manufacturing the jar, the rearing of the livestock, or the harvesting of the latex for the sealant. For more on this theme, see Thomas Thwaites creating a toaster ‘from scratch’ here or the definitive essay by Leonard Read, ‘I, Pencil’.

For any single individual, producing a jar of frankfurters alone would represent a monumental task. Together as a society, it becomes table stakes.

“There is no escape from the division of labour,” quips Kieran Healy. Our global societal fabric has become more deeply interconnected than ever before over the course of the last few decades.

A doomsday prepper may be able to hoard a year’s worth of supplies, but the division of labour and hyper-specialisation that enabled the creation of that hoard of supplies is not replicable on the individual level. After a year, they would be left hunting and gathering in the wild.

We are all dangling at the end of a supply chain.

Informational Supply Chains

Let’s take the idea of dangling at the end of a supply chain idea even further.

Not only do we depend on a vast array of physical processes to deliver the frankfurter jar to our shelves, but we also rely on a wealth of human knowledge and expertise deployed at each stage of production. In other words, not only are we dangling at the end of a physical, logistical supply chain, but we are also dangling at the end of a supply chain of knowledge and expertise - an epistemological or informational supply chain.

As I type these thoughts into my keyboard, I am aware that I have never yet understood how the physical pressing of computer keyboard keys transforms via an electronic binary system into digital on-screen text. I type away unencumbered by knowledge and the ignorance is blissful, perhaps even necessary. There is no need for the average user to comprehend the levels of abstraction involved in this seemingly spontaneous process.

Epistemic Learned Helplessness

What we are left with is what Scott Alexander terms ‘epistemic learned helplessness’ (epistemic simply shorthand for ‘relating to knowledge’).

In other words, the sheer scale of human knowledge, the number of bytes of information in existence, is not commensurate to the boundaries of our human computational and chronological limitations. Generally, the only sane approach to knowledge is to accept the received wisdom.

We may be multitudes, but we are finite:

Epistemic learned helplessness is knowing that any attempt to evaluate the arguments is a bad idea, so I don’t even try.

If you have a good argument that the Early Bronze Age worked completely differently from the way mainstream historians believe, I just don’t want to hear about it. If you insist on telling me anyway, I will nod, say that your argument makes complete sense, and then totally refuse to change my mind or admit even the slightest possibility that you might be right…

Given a total lack of independent intellectual steering power and no desire to spend thirty years building an independent knowledge base of Near Eastern history, I choose to just accept the ideas of the prestigious people with professorships in Archaeology, rather than those of the universally reviled crackpots.

Slate Star Codex on Epistemic Learned Helplessness,

The Sovereign Individual

For the past 350 years, the motto of the Royal Society has been nullius in verba, meaning ‘on the word of no-one’, or ‘take nobody's word for it’.

This aphorism encapsulates the ideal of intellectual autonomy. The pursuit of epistemic sovereignty remains popular and is often noted as a priority by members of the Silicon-valley tech establishment interested in the ‘sovereign individual’.

But in a world where more data is created each year than has ever before existed in all human history, for any one individual person to scratch even the surface of human knowledge is impossible. So the proposition that the only way to ascertain certain truth is to conduct empirical observation seems untenable:

The ideal of intellectual autonomy drove the Enlightenment but doomed itself, because it created all the science that made it impossible to be intellectually autonomous.

If you still hold to that ideal of intellectual autonomy (that everyone can understand everything) the eventual end result of that line of thinking is to be driven towards anti-vaxxing and various conspiracy theories in which you reject trust in the sciences.

Thi Nguyen on Sean Carroll’s Mindscape

So, can we be certain that any knowledge is accurate without empirically testing it? No, any piece of information may be incorrect.

Is going back to first principles on every question the right approach? No, that is an unsustainable epistemological strategy.

Alternatively, is resigning yourself to epistemic learned helplessness a sound strategy? Surely not, that seems an inadequate approach to knowledge.

SPIDES: The Spinach-Popeye-Iron-Decimal-Error-Story

The problem of relying on the expertise of others is perfectly summed up in a now celebrated paper by Mike Sutton published in the Internet Journal of Criminology about the Spinach-Popeye-Decimal-Error-Story.

To summarise the piece:

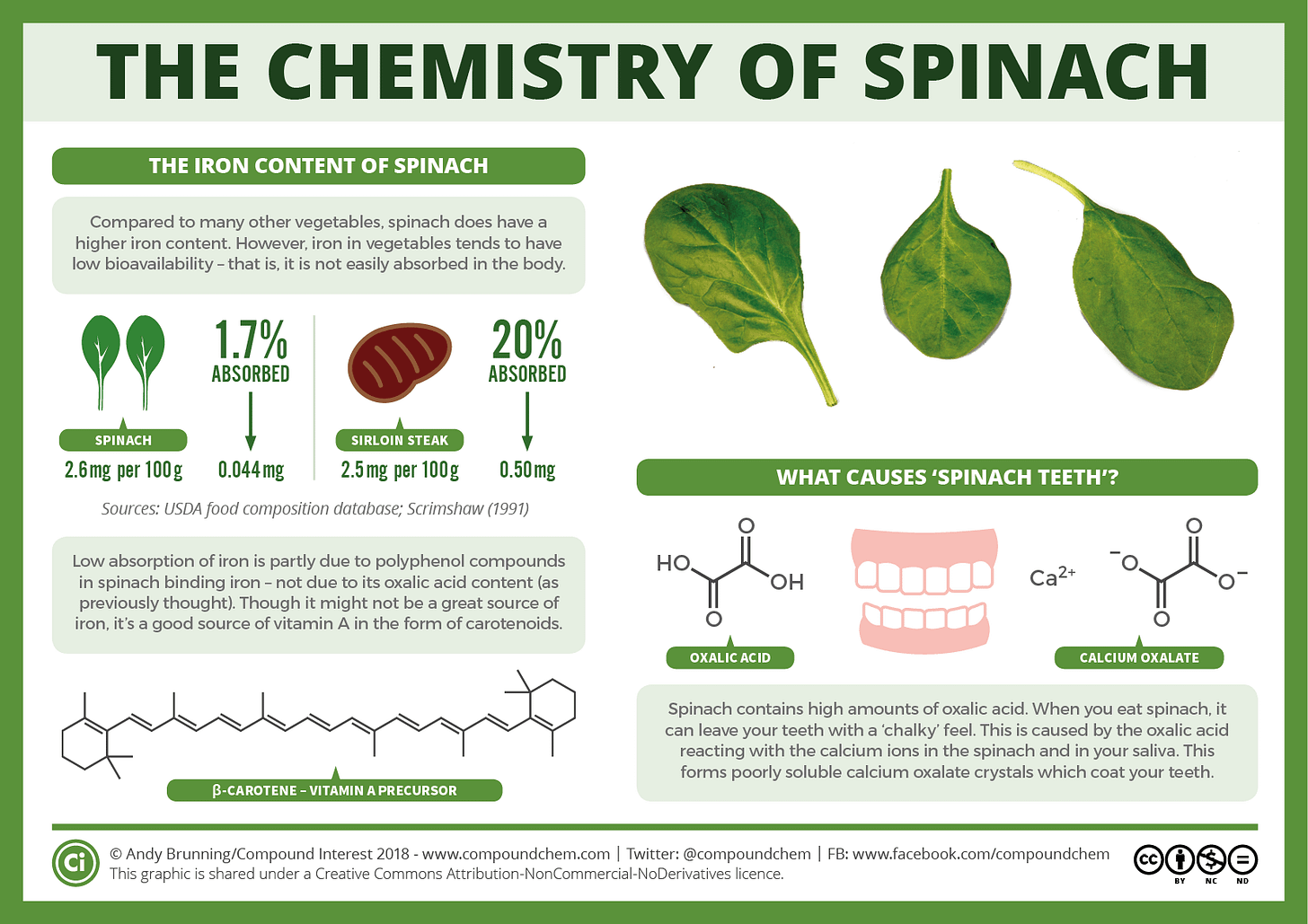

It is often claimed that spinach is a good source of iron for humans, but this is inaccurate. Although spinach’s iron content trumps that of many other vegetables, the bio-availability of that iron is very poor, meaning that it cannot be easily absorbed into the human body. This is unlike the ‘haem’ iron found in many other foods like red meat.

An early victim of the spinach-iron myth was the cartoon character Popeye. Popeye was known for eating spinach. His creator, Elzie Segar, chose spinach for Popeye on account of its high vitamin A content, not for its iron content. The wider public, however, incorrectly believed that the original comic strips promoted Popeye’s consumption of spinach for its iron content.

From as early as 1935, science journalists were making humorous associations between the comic strip character Popeye, iron and spinach.

In 1981, a consultant haematologist named T.J. Hamblin published a paper in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) entitled ‘Fake’ in which he brought to light the erroneous association between Popeye, Iron and Spinach. Interestingly, however, in the article Hamblin also made an additional claim (without any references to support the story) that the source of this confusion between iron and vitamin A was a 19th-century data error, a decimal error to be precise, which led to a tenfold exaggeration of the iron content of spinach that was perpetuated by generations of other scientists:

German chemists reinvestigating the iron content of spinach had shown in the 1930s that the original workers had put the decimal point in the wrong place and made a tenfold overestimate of its value.

T.J. Hamblin in Fake

Hamblin’s article, in turn, propagated this apocryphal Spinach-Popeye-Decimal-Error-Story ‘SPIDES’ story. Indeed, the story was cited by many writers as an example of the perfect typographical error or to illustrate the importance of fact-checking and accurate sourcing.

Such was the enchanting spell of Hamblin’s SPIDES claim, that even the most strident sceptics publishing papers about the importance of citation used the Spinach-Popeye-Decimal-Error-Story as a credible example of the need to be sceptical and read original sources. See, for example, ‘The dissemination of false data through inadequate citation’, by K.S. Larsson:

When unfounded statements are repeated frequently, they tend to be accepted: the difficulties in correcting such ‘accepted facts’ are well recognised. The myth from the 1930s that spinach is a rich source of iron was due to misleading information in the original publication: a malpositioned decimal point gave a 10-fold overestimate of iron content.

K.S. Larsson in Journal of Internal Medicine

But there is a final ironic twist. The only source provided by Larsson for the decimal error story is Hamblin (1981). Hamblin, however, never actually provided a source for his account of the decimal error story (see the original piece for yourself) and he was unable to provide it (when challenged later).

It appears that Larsson himself “disseminated false data through inadequate citation”. Larsson’s own comment that, “once a paper with misleading information has been published, it is almost impossible to stop citation,” held true all too well. It can be seen again and again.

On Collective Knowledge

The ‘Fractal Chain of Trust’

The decision to trust the expertise of others is what enables us to make intellectual progress.

But how should we know whose shoulders to stand on? At one level, we do not have the time or resources to empirically test every piece of knowledge on our own. But, what is more, we do not even have the capacity to pick the right experts to trust to provide that knowledge to us!

I’m a philosopher with a PhD in philosophy, arguably I have a lot of education. But if you gave me a real statistician and a fake one and they just had math on a wall, I don’t have the mathematical skills to tell the difference between a good statistical paper and one that gives a bad result.

So, what you get is this incredibly iterated and very fractal chain of trust. Literally, I trust this result because it came from someone who’s at Princeton University.

Thi Nguyen on Sean Carroll’s Mindscape

At present, we tend to use proxies, such as institutional statuses, as heuristics to determine whose expertise to trust. This means expertise is as much about belonging to a community of experts as it is about knowledge itself. But these proxies for expertise are not always reliable.

New technology has compounded the problem of trust.

On the plus side, it has democratised access to high-quality information and enabled new forms of validation and distribution of knowledge. Today, rather than an accredited institution, your peers can decide whether your insights are worth discussing via engagement on digital network platforms. Previously, sharing new ideas required centralised gatekeepers, like a university or a newspaper. Today, a popular blog post can reach an unlimited readership and anyone can build a portfolio of work online for all to see. For some types of research, it is now possible to pursue PhD-level work outside of formal academic institutions. You no longer need a title or certificate to demonstrate expertise in certain domains, you simply need to show your working.

On the other hand, new technology has also democratised access to false information. Ease of access to the sum of all human knowledge means that everyone can be a superficial expert on everything or dig deep into dark rabbit-holes of misleading information.

Network Epistemology & Heuristics for Expertise

Network epistemology is the study of how groups generate and propagate beliefs and one of its findings is that, where a particular belief is correlated with being well-connected, then soon everyone within a social network will believe that everyone else shares that belief. The result is that anyone who deviates from that set of beliefs must step outside the network and thus to surrender the claim to expertise. This can eradicate the heterodoxy that is needed for the diversity of thought that can overcome new challenges.

Network epistemology can explain why some non-specialists on the internet were able to make better predictions about the COVID-19 pandemic than the global public health and epidemiological establishment. By being outside the traditional network of expertise, these non-experts were better able to entertain unconventional beliefs that turned out to be closer to the truth than conventional wisdom:

In March 2020, I googled the word ‘epidemiology’ and read the Wikipedia page on ‘mathematical modelling of infectious diseases’. With COVID-19 arriving in full force in the U.S., I was anxious about the future (along with countless others), and I set out to build a machine learning model to predict the direction of the pandemic. One month later, my model at covid-projections19.com was included by the CDC as one of five COVID-19 models forecasting deaths. It soon was considered to be one of the most accurate. I was an untrained data scientist with zero prior experience in infectious diseases, but I became known as an ‘expert’ in COVID-19. Not that I did it alone — my model was a crowdsourced effort, because I received help and advice from countless individuals on social media.

Youyang Gu on a16z Future of Expertise

Although proxies for knowledge and expertise typically encompass institutions and government bodies, everyone will have their own individual set of trust heuristics.

A conspiracy theorist, for example, may have a framework of trust that excludes states and institutions, and in some cases, they are right – after all, plenty of historical governmental institutions have published misinformation and acted unethically.

Both for governments and for individuals, building an epistemological strategy that incorporates unconventional wisdom and takes heterodox ideas seriously without falling for misinformation will surely be one of the great challenges of the coming decades as the quantity of information, data, and opinions continues to grow exponentially.

Conclusion: The Human Colossus

In our digital age, perhaps more than ever, we are dangling at the end of a fragile supply chains.

In a world of hyper-speciliased expertise and complex global supply chains, we are increasingly dependent on fractal physical supply chains and heuristics of trust. No single individual can ever truly get to the bottom of anything beyond their own very narrow field of expertise.

Collectively, however, our human knowledge continues to grow at an ever-increasing rate. The unprecedented interconnectedness of our world enables us to leverage our time collectively with exponential benefits for the quality of all our lives. Collective human progress has been termed the ‘Human Colossus’ by one writer, Tim Urban, who envisages a sort of collective organism enabled by language, mass network communications, and computing technologies.

[Update December 2024: upon reading David Deutsch, I have subsequently discovered his extensive analysis of this phenomenon, termned ‘the beginning of infinity’].

Just as the world of the internet exposes us more and more to the mercy of epistemological supply chains, in equal measure, the internet gives us access to the sum of all human knowledge and offers us the chance to become more expert than ever before.

Our aim should be to separate the signals from the noise. We need to develop better intuitions and norms around when to rely on traditional expertise and when to look further afield. Moreover, we need to build better tools and institutions for distinguishing ‘contrarian and correct’ from ‘contrarian crank’ given how similar they can often appear.

This applies both at the level of an individual, as well as at a higher level – how, for example, might governments build more flexible institutions of trust?

Building better frameworks like these is, in part, what this site strives towards.

At present, these are a draft set of guidelines for how an approach that I am taking to the vast universe of information available to us:

At any given point in time, seek to work on at least one subject via first principles thinking. Cultivate deep domain knowledge of the subject. In my case, two examples would be (i) the mechanics of financial systems and (ii) folk singing traditions in the British Isles.

When relying on proxies (likely the case for over 99% of what I believe) vary those proxies. This variation should increase the likelihood that the proxies do not incorrectly converge on important matters.

Use sources that conflict with each other at least some of the time, so that there is cause to question the underlying assumptions. At least some of those sources should be heretics in their field.

Thank you for reading and making it all the way to the end.

Please reply if you have comments, questions or suggestions. Please help me identify my errors so that I am able to update my priors. Do not hesitate to reach out.

Subscribe to receive new editions of this blog, delivered directly to your inbox.

I look forward to hearing from you!

~ N

Bibliography

Relating to collective knowledge:

Thomas Thwaites creates a toaster ‘from scratch’ here. Along similar lines, Leonard Read’s famous essay here: ‘I, Pencil’.

Tim Urban takes on the future trajectory of the Human Colossus in relation to artificial intelligence is available here: Neuralink. See also Tim Urban on Invest Like the Best podcast.

James Dale Davidson, William Rees-Mogg, ‘The Sovereign Individual: Mastering the Transition to the Information Age’. Yuval Noah Harari’s reaction to Silicon Valley’s positive reception of his work here.

Relating to expertise:

The future of expertise from a16z: Matt Clifford; Nadia Eghbal; Youyang Gu.

Kevin Zollman (2013) on ‘Network Epistemology: Communication in Epistemic Communities’, available here.

Relating to Popeye and Spinach:

Mike Sutton (2010), ‘Spinach, Iron and Popeye: Ironic lessons from biochemistry and history on the importance of healthy eating, healthy scepticism and adequate citation’ . Available here.

T.J. Hamblin (1981), ‘Fake’

Relating to transportation:

Transportation carbon footprint data can be downloaded here from Our World in Data. Methodology described by UK government department here. News here and here.

Quantitative analysis of container ship backlogs by Michael Tran, RBC Capital Markets LLC: ‘Digital Intelligence Strategy: One Ship, Two Ship, Slow Ships, More Ships’ published Sep-16, 2021.

What happened to the Ever Given?