Francis Galton’s ‘English Men of Science’

In 1874, Francis Galton, a British polymath, conducted a study that he titled ‘English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture’. The analysis that Galton produced still makes for fascinating reading today.

The purpose of Galton’s enquiry was multi-faceted and is explored in some detail in his section called ‘Nature and Nurture’ (pp.12-16). Galton poses questions such as: “How can the tastes of men be most powerfully acted upon, to affect them towards science?” (p.233).

Galton outlines his methodology for answering these research questions in an Appendix. There, he describes how he sampled English scientists by asking them to complete a questionnaire:

My schedule of printed questions, together with the ample spaces left for replies, filled, I am half ashamed to acknowledge, seven huge quarto pages.

Francis Galton, English Men of Science, p.261

Galton apparently announced his research intentions at a meeting of the Fellows of the Royal Society of London. Following the meeting, he received a copious supply of responses from his peers. Presumably, they were impressed by the scientific nature of his approach:

My data are the autobiographical replies to a very long series of printed questions addressed severally to the 180 men… Those of the answers which are selected for statistical treatment somewhat exceed 100 in number.

Francis Galton, English Men of Science, p.10

Galton is still considered an innovative and influential polymath (and, notably, he was also a first cousin of Charles Darwin). Crucially, however, and to his great discredit, Galton was a remarkably prejudiced individual, even for his own times.

In particular, Galton was a leading proponent of social Darwinism, eugenics, and scientific racism. In fact, even within this study, parts of the analysis stray into the field of eugenics, expressing views that are racist and misogynistic. See for instance, the section entitled ‘Race and Birthplace’ (pp.16-21).

So why have I brought this text to our attention this week?

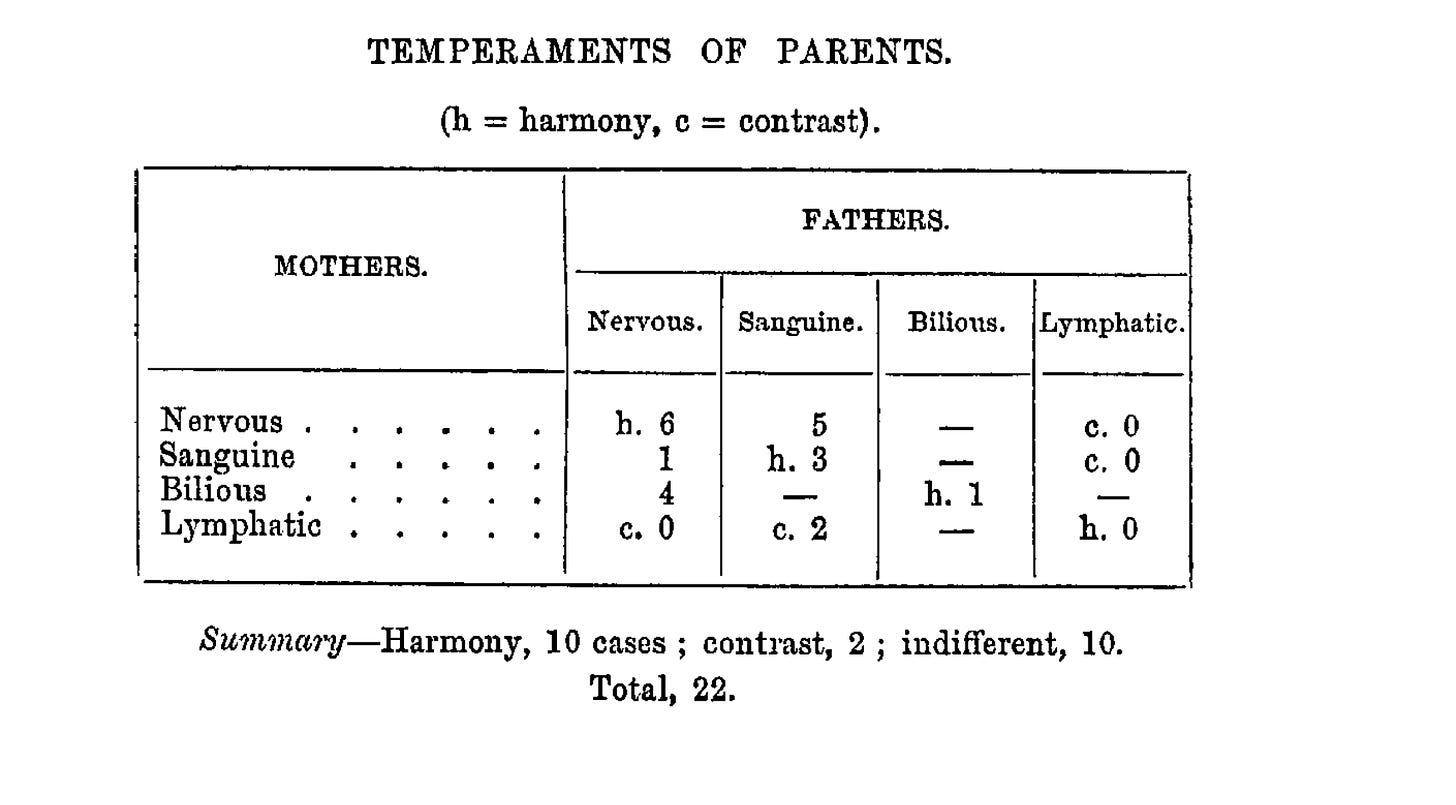

First of all, because I find the text utterly intriguing. Not only are the many anecdotes and biographies of Victorian scientists highly entertaining, but Galton’s statistical approach is revealing of his life and times. See, for instance, the following excerpts for a flavour of the Victorian nature of Galton’s scientific methodology, use of language, and conceptual frameworks:

Second, and more importantly, Galton’s study is of interest to me today because it represents the first known empirical analysis of birth order.

On birth order, Galton records these notes:

The following shows, in percentages, the position of the scientific men in respect to age among their brothers and sisters :

Only sons, 22 cases;

Eldest sons, 26 cases;

Youngest sons, 15 cases.

Of those who are neither eldest nor youngest, 13 come in the elder half of the family; 12 in the younger half; and 11 are exactly in the middle.

Total, 99.

Francis Galton, English Men of Science, p.33

Interestingly, Galton found that the majority of the English scientists in his dataset were firstborns and only children. He concluded as follows:

Elder sons have, on the whole, decided advantages of nurture over the younger sons:

They are more likely to become possessed of independent means, and therefore able to follow the pursuits that have most attraction to their tastes;

They are treated more as companions by their parents, and hare earlier responsibility, both of which would develop independence of character;

Probably, also, the first-born child of families not well-to-do in the world would generally have more attention in his infancy, more breathing space, and better nourishment, than his younger brothers and sisters in their several turns.

Francis Galton, English Men of Science, pp.34-35

Whether or not Galton’s conclusions are in any way correct, it seems to me that he had identified a fascinating subject of study.

Over the subsequent 150 years, many more studies have been conducted that suggest that birth order plays a crucial role in many aspects of our lives.

Birth Order & Financial Risk Tolerance

For the remainder of this piece, I will explore the extent to which birth order influence an individual’s propensity to take risks across different contexts and, in particular, in financial contexts.

There is a broad range of research that supports the notion that later-born individuals have a higher propensity to take risks and are associated more with sensation-seeking behaviours than their firstborn counterparts.

Specifically, later-born children have been associated in the research with the following characteristics: riskier adolescent behaviours1; tendency to participate in risky sports (and to take more risk during the game)2; greater desire to have more sexual partners3; greater internal sensation novelty seeking behaviour4; propensity for making riskier decisions5; and higher rates of self-employment6.

In my reading, I came across two papers relating to financial risk-taking that I found to be of particular interest. I share these both below.

Investment Fund Managers

The first paper, published in August 2022, investigates the role of birth order on the risk-taking behaviour of investment fund managers:

We find that managers who are born later in the sibling hierarchy take on more investment risks relative to first-born managers, but perform worse.

On taking on more investment risks:

Our primary findings indicate that mutual fund managers who are born later in their families take on more investment risks relative to those managed by individuals of lower birth ranks.

Funds run by later-born managers take 0.84, 0.26, and 1.13 percentage points more total risk, idiosyncratic risk, and active risk, respectively, relative to funds managed by firstborns.

Moreover, the later a manager is born in the sibling hierarchy, the higher is the propensity to take risks. We find that on average each one-unit increase in birth order, all else equal, translates to a 0.37, 0.15, and 0.65 percentage points per annum increase in total risk, idiosyncratic risk, and active risk, respectively.

On performing worse:

The observed birth order-induced heterogeneities in incremental risk-taking do not translate into a higher risk-adjusted performance. On the contrary, our results suggest that risk-adjusted performance decreases in a manager’s birth order.

Birth Order and Fund Manager's Trading Behavior: Role of Sibling Rivalry, Vikas Agarwal, Alexander Cochardt, & Vitaly Orlov.

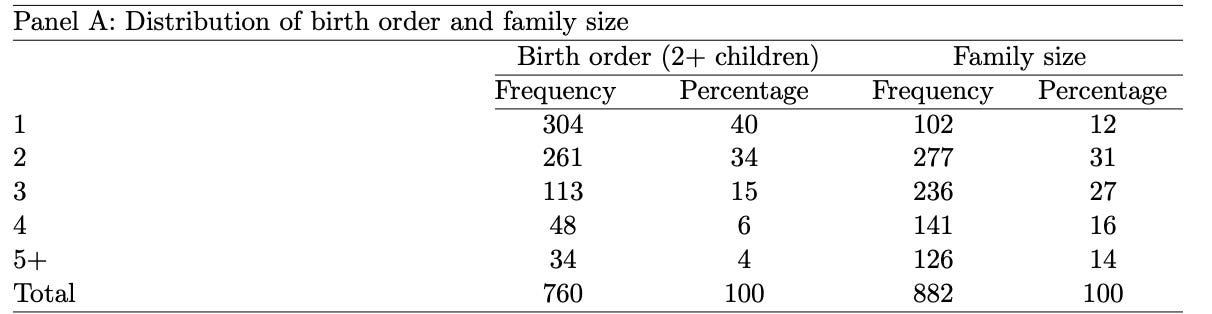

In order to conduct this study, the researchers constructed a new and comprehensive dataset that mapped US mutual fund managers’ family backgrounds to their fund’s investment performance. The sample included individuals who were the sole manager of a U.S. active equity fund for at least one full year between 1962 and 2017.

As you might imagine, data on fund investment performance is relatively easy to capture; the researchers report that they used financial data providers Centre for Research in Security Prices and Morningstar.

On the other hand, information about the family structures of the fund managers is much more difficult to source. The researchers’ primary source of information was apparently obituaries published in memory of deceased members of a manager’s family (!)

The researchers’ decision to use a sample of investment fund managers seems well-founded for a number of reasons.

First, the actions of mutual fund managers are directly observable and measurable, including multidimensional risk choices. In particular, the researchers could identify risk choices made in terms of portfolio composition, trading decisions, return volatility, and violations of professional business conduct.

Second, fund managers are likely to be solely responsible for their fund’s risk choices. And, third, fund managers are a relatively homogenous group of individuals (e.g., most of them have experience and training in finance), which allows for comparable counterfactuals.

Reassuringly, the sample sizes for the observations are very large (see table above). Similarly, the distribution of managerial family structures and characteristics is very similar to that of the United States population, which reduces the likelihood of selection bias. Moreover, the researchers ran a number of control experiments, controlling for managerial attributes that prior literature has shown can influence fund manager behaviour, including controls for: cultural origins; marital status; educational attainment; bereavement experience; growing up in depression era; and relative age.

Furthermore, the researchers ran a placebo experiment with a sub-sample of index funds (these being funds that are run passively by a manager who does not take risk decisions). This placebo test showed no birth order effects, further corroborating our main findings.

The researchers conclude:

Motivated by sensation seeking, later-born managers take extreme style bets, hold more lottery stocks, and report more civil and regulatory violations compared to lower-birth-order managers.

Taken together, our findings suggest that birth order-induced sensation seeking tendencies originate from sibling rivalry for limited parental resources during childhood, shape trading behavior, and extend beyond portfolio management.

Birth Order and Fund Manager's Trading Behavior: Role of Sibling Rivalry, Vikas Agarwal, Alexander Cochardt, & Vitaly Orlov.

Chief Executive Officers

The second paper, published August 2019, examines risk-taking and birth order among South Korean CEOs.

In South Korea, family-controlled business groups are known as Chaebols. These businesses are typically owned and managed by a family dynasty and consist of multiple private or public companies that are legally independent of one another and operate across multiple industries.

In 2015, the largest Chaebols consisted of an average of approximately 28 affiliated companies. Some prominent examples of Chaebols are Hyundai, Samsung, and the LG Group.

Here, the researchers’ decision to use family-owned businesses is an ingenious way to ameliorate the significant data collection challenges involved in finding family background information.

The researchers found South Korea to be a suitable candidate because of the level of disclosure demanded of businesses, which enabled them to obtain detailed personal information about the families behind the business groups. Likewise, there was an existing body of data from researchers and media organisations who had previously traced Chabeol families’ histories across several decades and made the information publicly available through news articles and books.

The researchers measured risk taking by aggregating three major outlays typically associated with uncertain and potentially negative returns: capital expenditures, research and development (R&D) spending, and acquisitions. This data was sourced from the Korea Listed Companies Association.

A potential weakness of this CEO study versus the investment fund manager research is that the risk decisions and their outcomes are less directly observable. In particular, the extent to which CEOs can affect firm outcomes is debatable. For instance, industry experts and academics have rated South Korean CEOs as having relatively low levels of managerial discretion compared to CEOs in other countries due to cultural norms as well as South Korea’s legal and regulatory systems which can inhibit CEOs’ influence over stakeholders such as employees.

Moreover, on average, CEOs in the sample had about five siblings and were predominantly born in the 1940s-1950s. This average family size is higher than the general population, which may indicate some selection bias. Further, the total sample size is smaller, consisting of 71 CEOs across 67 firms, all of whom were males. This extreme gender imbalance is somewhat striking, but the researchers note that South Korea ranks low in global studies of gender equality and CEOs in many other jurisdictions are also predominantly male, (sadly) making the study more generalisable.

One further complication is that, in family business groups, multiple siblings tend to be involved, with some siblings serving as CEOs of independent firms at the same time—a condition that the researchers argue contributes to ongoing sibling rivalry.

Taking those limitations into account, nonetheless, the results make for compelling reading.

We find that… the later the order of birth, the more strategic risk CEOs undertake, and this tendency is more pronounced when the conditions for sibling rivalry (a key mechanism explaining birth order effects) are salient due to small age gaps with their siblings and the presence of a sibling CEO.

Contrary to our theorizing, the impact of CEO birth order on strategic risk taking does not diminish as CEOs age. This unexpected finding reinforces the idea that birth order effects have a strong lasting effect on individuals, including CEOs.

Born to Take Risk? The Effect of CEO Birth Order on Strategic Risk Taking, Robert Campbell, Seung-Hwan Jeong, & Scott Graffin.

Parting Thoughts

All the most compelling research that I have read suggests that younger siblings take more risk than older siblings.

Anecdotally and intuitively, this seems correct? Think Prince Harry versus Prince William.

Risk tolerance and birth order are rich areas of study. As someone who has spent some time working in investment and wealth management, I find them particularly fascinating and pertinent to challenges that are often observed among private clients. What is more, beyond birth order, there are an abundance of other variables to explore in relation to financial risk tolerance, such as gender, age, education, and income.

As a final note, I should declare my conflict of interest. I am, myself, an eldest child. As we now know, this of course means that I am much more responsible, persistent, and emotionally stable than my second or third born siblings.

Thank you for reading.

Bibliography

Key reading of research studies:

Birth Order and Fund Manager's Trading Behavior: Role of Sibling Rivalry (2022) Vikas Agarwal, Alexander Cochardt, & Vitaly Orlov.

Born to Take Risk? The Effect of CEO Birth Order on Strategic Risk Taking, (2019) Robert Campbell, Seung-Hwan Jeong, & Scott Graffin.

Firstborn CEOs and credit ratings, (2022) June Woo Park, Giseok Nam, Albert Tsang, & Yung-Jae Lee, The British Accounting Review

For Galton see:

Galton, F. (1874). English men of science: Their nature and nurture. London, England: Macmillan.

A Guide to Francis Galton's English Men of Science, Victor L. Hilts, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 65, No. 5 (1975), pp. 1-85

Adam Rutherford (2020), How to Argue with a Racist: What Our Genes Do (and Don’t) Say about Human Differences

My inspiration to research this topic was originally sparked by these two posts:

Argys, Laura M., Daniel Rees, Susan Averett, and Benjama Witoonchart, 2006, Birth order and risky adolescent behavior, Economic Inquiry 44, 215–233; Averett, Argys Laura M., Susan L., and Daniel I. Rees, 2011, Older siblings and adolescent risky behavior: does parenting play a role?, Journal of Population Economics 24, 957–978.

Sulloway, Frank J., and Richard L. Zweigenhaft, 2010, Birth order and risk taking in athletics: A meta-analysis and study of major league baseball, Personality and Social Psychology Review 14, 402–416.

Michalski, Richard L, and Todd K Shackelford, 2002, Birth order and sexual strategy, Personality and Individual Differences 33, 661–667

Zweigenhaft, Richard L., 2002, Birth order effects and rebelliousness: Political activism and involvement with marijuana, Political Psychology 23, 219–233.

Roszkowski, Michael, 1999, Risk tolerance in financial decisions, Fundamentals of Financial Planning, 179–248; Gilliam, John, and Swarn Chatterjee, 2011, The influence of birth order on financial risk tolerance, Journal of Business and Economics Research (JBER) 9, 43–50.

Black, Sandra E., Erik Gr¨onqvist, and Bj¨orn Ockert, 2018, Born to Lead? The Effect of Birth ¨ Order on Noncognitive Abilities, The Review of Economics and Statistics 100, 274–286.