On a recent holiday, I read a book titled ‘Outlive: Rethinking Medicine to Live Better, Longer’ by Dr Peter Attia.

Many of the book’s messages resonated with me, so I will now subject you to my thoughts and reflections on the text. In particular, I will reflect on Attia’s approach with reference to Seneca’s ‘On the Shortness of Life’. In comparing Seneca’s philosophical outlook on longevity with Attia’s approach, I will ask: what does it mean to outlive?

On Longevity

Dr Peter Attia is a longevity guru and talking head. As a public persona, Attia makes appearances on a broad sweep of self-improvement podcasts and shows. Indeed, as much as it pains me to admit it, I first came across Peter Attia on Steven Bartlett’s podcast.1

As Attia himself often likes to remind an audience, he is a former surgical oncologist and later trained as a financial risk manager, so his credentials are relatively robust. These days, as far as I can discern, Attia operates a medical practice for an ultra-wealthy elite. These individuals reportedly part with hundreds of thousands of dollars each year to retain him as their personal physician and medical adviser.

In summary, this book ‘Outlive’ is a sort of manifesto that outlines Attia’s principles for maximising longevity. The book itself is not particularly well edited and is riddled with clichés, but the ideas that Attia amalgamates in this book, while simple, are powerful when considered in combination.

Attia refers to his approach as ‘Medicine 3.0’ (exempli gratia of aforementioned cliché). In his words:

The aim is to outlive… not to achieve a faster marathon time or bragging rights at the gym, but to live a longer and better life, and most importantly, a life in which you can continue enjoying physical activity well into your later years.

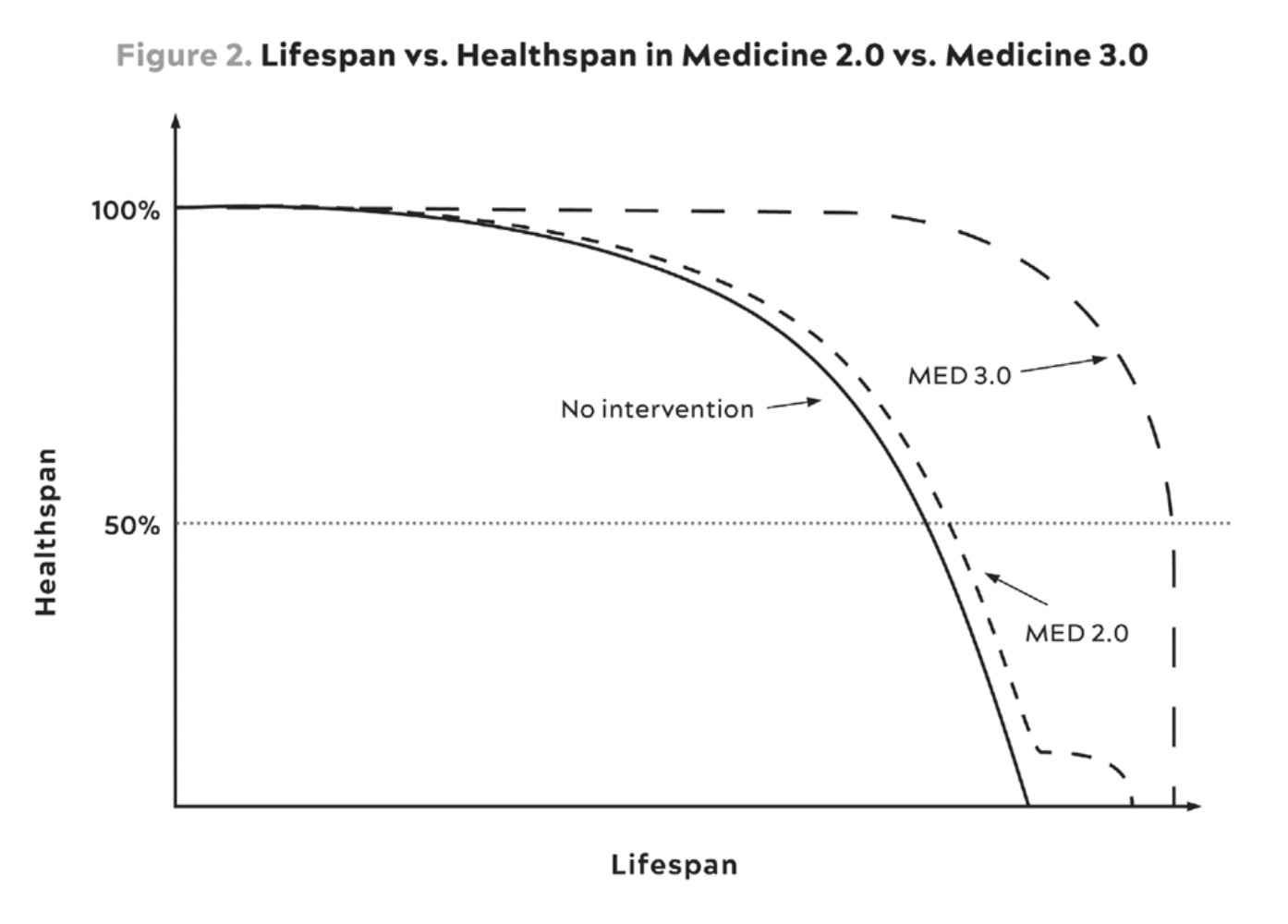

In short, Attia wants not only to increase longevity, but also the quality of life. In doing so, he differentiates between lifespan and what he terms ‘healthspan’. Attia again:

The goal is not to increase lifespan (how long we live), but to increase healthspan (how long we can live healthy enough to do the things we enjoy).

We want to spend as little time as possible in a state of decreased mental, physical, or emotional capacity. Ideally, we would all enjoy long, healthy, fruitful lives and then have a quick descent to the end of our lives, without years of decreased capacity and disease.

He illustrates this difference with the following visual prompt:2

And to further reinforce the concept of healthspan, Attia asks the reader to perform the following thought experiment:

Devise a list of 10-20 things you would like to be able to do in your final decade of life.

To get the ball rolling, Attia offers the following illustrative examples:

Hike through a forest for 30 minutes.

Stand up from the floor using your own power (only one arm for support).

Pick up a young child from the floor.

Carry two bags of shopping from the local shop to home.

Lift a small suitcase into an overhead compartment

Balance on one leg for thirty seconds, eyes open

Sleep for 6 hours each night consecutively.

Have a 1-hour conversation on a specialist subject.

Have sex with a partner.

Climb 4 flights of stairs in 3 minutes.

Open a jar.

Do 30 consecutive skipping-rope jumps.

This thought exercise very much gripped my attention. For context, I am extremely fortunate to have several very long-lived grandparents, currently enjoying their ninth decade of life. Seeing up close the trajectories of their respective healthspans has given me cause to reflect in recent years. Observing the longevity of their mental and physical health, and the pathways into decline that they are experiencing, I increasingly wonder how I might maximise the chance of enjoying good health for as long as them.

In the opening section of his book, Attia first and foremost acknowledges that genetics play a significant role in determining an individual's lifespan, discussing factors involved in the genetic lottery that is healthspan.

Attia tells several amusing anecdotes about eccentric centenarians such as the world’s longest-lived person ever verified, the French woman Jeanne Calment, a supercentenarian who lived until 122 (from 1875 until 1997). She supposedly once joked, “I’ve only ever had one wrinkle, and I’m sitting on it” and kept smoking until the age of 117. There are plenty of other remarkable stories besides. For instance, Polish-born Yisrael Kristal suffered as a forced labourer at Auschwitz, thereby surviving the Holocaust, and yet still lived to age 113 and is amongst the top ten longest lived men ever recorded.

Contrastingly, Attia also shares several tragic anecdotes about his own family members who died prematurely as a result of genetic predispositions to cardiovascular conditions.

He writes:

If you do happen to have centenarians in your family tree, let me offer my congratulations. Such genes are, after all, a form of inherited luck.

And asks:

Can we, through our behaviours, somehow reap the same benefits that centenarians get for ‘free’ via their genes? Can we mimic the centenarians’ phenotype, the physical traits that enable them to resist disease and survive for so long, even if we lack their genotype? Is it possible to outlive our own life expectancy if we are smart and strategic and deliberate about it?

Then, Attia moves into the heart of the book, turning our attention away from the inevitability of genetic factors towards the tactical domains that any one of us can address in order to alter our own healthspan. Attia is clear that, while genetics provide a baseline for longevity potential, lifestyle choices significantly influence how those genetic predispositions manifest themselves.

Attia is particularly interested in the ways in which these lifestyle choices influence our risk of dying from some of the most common chronic diseases: cancer; heart disease; type 2 diabetes; and dementia.3

In short, the key features of Attia’s approach are:

Exercise.

Nutrition.

Sleep.

Emotional Health.

Pharmacology.

Hang on…

Isn’t it obvious, blindingly obvious even, that those would be the key features of longevity?

Well, it is obvious. But that is precisely the point. None of the insights offered in Attia’s book are in any way ground-breaking. The beauty of his message is that the levers for improving longevity are profoundly simple (except for those which are genetically determined). To outlive, you do not have to absorb hours of content from influencers, buy their latest products, or follow their fad diets, though you may find yourself reading Attia’s book…

It is the very simplicity of Attia’s approach that makes it a rather difficult programme to follow. There is no hack, there is no elixir. There is no pill that we can take to extend life.

Exercise.

Attia considers exercise to be by far the most potent domain for any given individual to take change the course of their own lifespan and healthspan. In short:

Exercise as much as possible.

Any exercise above zero is better than doing nothing.

Do a wide variety of exercise.

Specifically, Attia favours cross-training and generalisation in exercise. He measures success in terms of three main components:

Aerobic measures. Aerobic efficiency and maximum aerobic output (VO2 max, which is the maximum (max) rate (V) of oxygen (O₂) your body is able to use during exercise).

Strength. For fast-twitch ‘type 2’ muscle fibres and bone mineral density.

Stability. To avoid injury through flexibility, form, and cross-training.

Attia lays out study after study to establish a causal link between exercise and health, demonstrating that regular exercisers live longer than their more sedentary counterparts (typically, as much as a decade longer).

Each study that he references is selected for being of the highest available quality. Yet, he is very open about the limitations of this approach. He writes:

Living systems are messy, and confounding, and complex. Our understanding of even fairly simple things is constantly evolving.

The best we can hope for is reducing our uncertainty. A good experiment in biology only increases or decreases our confidence in the probability that our hypothesis is true or false.

In the absence of multiple, repeated, decades-long, cross-species, randomised clinical trials that might answer our questions with certainty, we are forced to think in terms of probabilities and risks.

In his view, peak cardiorespiratory fitness (as measured by VO2 max) is the most effective and accessible predictor of longevity that we have at present.

Being below average in your age category in terms of VO2 max leads to a 2-4x greater increased risk in all-cause mortality (death from any cause) compared to the group with the highest fitness level (Kokkinos et al 2022).

Muscle strength (not size) is another metric that Attia identifies in the clinical literature as a strong predictor of health and lifespan. For instance, he references a study showing that muscle lean mass is a strong predictor of all-cause mortality (specifically, the appendicular lean mass index which measures the muscle mass of their extremities, arms and legs, normalised to height).

Attia writes:

Seniors with the least muscle mass (also known as lean mass) are at the greatest risk of dying from all causes.

One Chilean study looked at about 1,000 men and 400 women, with an average age of 74 at enrolment. The researchers divided the subjects into quartiles, based on their appendicular lean mass index, and followed them over time.

After 12 years, approximately 50% of those in the lowest quartile were dead, compared to only 20% of those in the highest quartile for lean mass.

Whilst this study alone cannot establish definitive causality int his case, the strength and reproducibility of these findings suggest that this is more than simple correlation. Given that ‘falls’ are by far the leading cause of accidental death amongst the oldest cohort of the US population, it is not difficult to infer why there may be a causal relationship between strength and all-cause mortality.

Most remarkable of all, for me at least, is a study referenced by Attia that suggests that another proxy measure of strength, greater handgrip strength, is directly correlated with having a lower risk of developing dementia (Esteban-Cornejo et al 2022).

Elsewhere, Attia highlights that habitual exercisers do not only tend to live longer, but they also stay in better health, with less morbidity from causes related to metabolic dysfunction (citing Booth & Zwetsloot 2010).

Interestingly, these studies indicate that the benefits of exercise begin with any amount of activity north of zero. In other words, even a brisk walk represents a vast improvement over remaining sedentary for your health (Citing Lee & Buchner 2008).

Nutrition.

Attia’s approach to diet, nutrition, and nutritional biochemistry is also disarmingly simple. In brief:

Eat food.

Do not eat too much food.

Eat mostly plants.

The key questions Attia poses when considering any given individual are:

Are they over nourished or undernourished?

Are they under muscled or adequately muscled?

Are they metabolically healthy or not?

Attia favours achieving an optimal caloric intake without cutting out specific food groups to maintain healthy weight and metabolism. But he does advise the following specific measures:

Eliminate fructose-sweetened drinks.4

Avoid alcohol. Learn how your body responds to foodstuffs via continuous glucose monitoring.

Consume sufficient protein, but over the course of the day rather than in a single sitting.

Favour monosaturated and polyunsaturaed fatty acids, minimise saturated fats.

And other practical advice that I found enjoyable included:

Buy fresh produce and take the time to prepare it yourself.

Become a chef for yourself and for your friends.

Use the best oils you can get. Undercook whenever possible and eat raw vegetables. Use good salt. Use great spices.

Add food containing fibres like beans and lentils.

Don't buy ultra-processed food. Avoid processed meat.

Limit ordering prepared food. Don't eat out in places that might use ultra-processed ingredients or low quality meat and vegetables.

When drinking, buy the most expensive red wine and champagne you can afford. It has a different quality and will prevent you from drinking too much.

Sleep.

Next, Attia prioritises sleep. His advice, in order of priority, can be summarised as follows:

Maintain the consistency of wake time (even on weekends).

Improve quality of sleep by adjusting temperature and light, minimising anxiety-inducing activities at bedtime, reducing alcohol intake, and limiting food consumption after dark.

Increase sleep duration (less than 7 hours per night is typically associated with worsened health outcomes).

Emotional Health.

Attia also identifies emotional health as a component of overall well-being and longevity. In particular, he outlines the connection between emotional and physical health, recognising that emotional stress and psychological factors can have profound effects on the body's physiology and contribute to the development of chronic diseases.

Attia advocates for strategies to manage emotional health and to develop resilience in the face of life's challenges. For instance, he suggests:

Mindfulness practices.

Meditation.

Exposure to daylight.

Time in nature.

Spending time with family, friends.

Cultivating supportive relationships.

Dialectical behaviour therapy.

Overall, the key message from Attia is the fundamental importance of addressing emotional stressors as part of a comprehensive approach to health optimisation.

Pharmacology.

Finally, Attia surveys pharmacological interventions. He makes clear that, in his view, although relevant for particular conditions, pharmacology is the least important domain.

By pharmacology, he means any exogenous molecules: drugs, supplements, and hormones. Chief amongst these molecules for him are statins and other cholesterol and lipid-lowering drugs, although he emphasises that additional testing is necessary for any given individual to find out which medications in which combination are most appropriate. It should be taken as read that I am medically illiterate, so my ability to evaluate this part of the book is impaired by my status as a lay-person. To this end, however, Attia offers a mercifully simplified primer on several disciplines within medicine, with particular focus on cardiology and oncology.

Finally, Attia enumerates an eye-watering range of screens and scans that he advises his ultra-wealthy patients to undertake. Above all, he is an advocate for early detection of underlying problems. As a result, Attia has patients undergo testing earlier and more frequently than most other healthcare professionals would advise. If of interest, I list the tests that are mentioned in the book in the Appendix, all of which, Attia informs us, can be conducted without a medical referral… for a price!

Seeing the Wood for the Trees

By and large, I was strongly convinced of Attia’s framework for improving longevity and even the minutiae of his approach. This is perhaps because his proposed approach aligns with my intuitive vision of a healthy lifestyle.

What’s more, under the gimmicky exterior, Attia is surprisingly measured and empirical. He refuses to engage in binary absolutes. When asked by a friend, “should I do more cardio or more weights?” Attia’s response is to reject the binary premise of the question. Instead, he proposes that it is possible to have your cardio and lift it…

This balanced, pragmatic approach extends also to questions around nutrition, exercise and sleep. On several key topics of debate, Attia also demonstrates his ability to adapt to new information that challenges his beliefs. When presented with evidence that contradicts his understanding, he update his priors accordingly. In my view, Attia’s epistemic humility, by which I mean his ability to recognise the incomplete-ness of his own knowledge, helps distance his doctrine from the sort of bio-hacking, death-cheating bro-science that often mires discourses around longevity.

That said, I am still unsettled somewhat by Attia’s pursuit of longevity.

Attia is uncompromising, verging on fanatical and he himself is the ultimate test subject for his all-consuming health regime. As much as I agree with the contents of his book, the obsession with maximising healthspan seems somehow deficient, leaving little room for anything else. Admittedly, the closing chapters of the book expand on the significance of emotional health in achieving a longevity but still I found myself wondering: does Attia occasionally loses the wood for the trees?

What of the soul?

And to that end, let’s now turn briefly to Seneca.

On the Shortness of Life

de brevitate vitae (‘On the Shortness of Life’) is a text presented in the style of a letter from the author, Seneca the Younger, to a friend called Paulinus.

In the letter, Seneca ruminates on the nature of human life and, in doing so, considers longevity.

The main thrust of Seneca’s argument is as follows: people often lament the brevity of life when, in reality, they waste vast swathes of their life on trivial matters. Seneca reflects on what it means to use time wisely and how to live more meaningfully rather than merely existing for a long time. In particular, Seneca takes great pleasure in disparaging anyone who pursues longevity for its own sake.

For Seneca, it is not the length of the life that we live that matters, but how we use the time at our disposal. In his view, it is better to live fully and virtuously for a short time than to live for many years without purpose or fulfilment.

I very much agree with Seneca on all these points. It is only where he draws his conclusion that he begins to lose me somewhat. For Seneca, the ultimate way to live virtuously is to study philosophy (see XIV below). Readers will no doubt determine for themselves whether they find this to be a convincing conclusion to draw.

It is worth reading Seneca’s text in full. However, given that not everyone has the time to read Latin philosophical texts, below I have excerpted and translated a series of passages from de brevitate vitae that, in my view, represent the key highlights from the text:

I. ita est: non accipimus brevem vitam, sed facimus, nec inopes eius sed prodigi sumus… non exiguum temporis habemus, sed multum perdidimus… exigua pars est vitae qua vivimus.

The life that we receive is not short, but we make it so. We are not time poor, rather we are profligate with our time. It is not that we have only a short span of time, but rather that we waste so much of it. Short is that part of life that we truly live.

II. vita, si uti scias, longa est… sicut amplae et regiae opes, ubi ad malum dominum pervenerunt, momento dissipantur, at quamvis modicae, si bono custodi traditae sunt, usu crescunt. ita aetas nostra bene disponenti multum patet…

Life, if you know how to use it, is long. The greatest of inherited fortunes will be squandered in no time at all if it comes into the hands of a bad owner. Yet, the most modest wealth, if entrusted to a prudent custodian, increases by use. In the same way, our life is amply long for the person who orders it properly.

quam multis nihil liberi relinquit circumfusus clientium populus… bonis suis effocantur… alius in alium consumitur.

How many people are crowded about by a throng of clients that leaves them no freedom? These people are smothered by their blessings. Each is wasted for the sake of another.

III. quotus quisque dies ut destinaveras recesserit, quando tibi usus tui fuerit?… quam multi vitam tuam diripuerint te non sentiente quid perderes. quantum vanus dolor, stulta laetitia, avida cupiditas, blanda conversatio abstulerit, quam exiguum tibi de tuo relictum sit.

How few days have passed as you had intended, when you found yourself at your own disposal?

How much of your life was snatched from you without you realising what you were losing?

How much of your life was taken up in useless sorrow, in foolish joy, in avaricious desire, or in the temptations of society?

How little of yourself was left to you?

IV. qui omnia videbat ex se uno pendentia, qui hominibus gentibusque fortunam dabat, illum diem laetissimus cogitabat quo magnitudinem suam exueret.

[On the subject of the Emperor Augustus, who always dreamt of taking a break from his duties]

That man who alone ruled over everything, who determined the fortune of individuals and of nations, longed for that future day when he might lay aside his greatness.

IX. ut possint vivere, impendio vitae vitam instruunt. illa eripit praesentia dum ulteriora promittit

Too many people keep themselves busily engaged just so that they might be able to live better in the future. They spend their whole lives preparing to live!

optima quaeque dies miseris mortalibus aevi /

prima fugit.

[Quoting Virgil’s Georgics]

Wretched is mortality, for the fairest day /

Is ever first to flee.quorum puerilis adhuc animos senectus opprimit, ad quam imparati inermesque perveniunt, nihil enim provisum est. subito in illam necopinantes inciderunt, accedere eam cotidie non sentiebant.

Old age creeps up on people while their minds are still immature. They find themselves facing it totally unequipped and unarmed. All of a sudden, unexpectedly, they stumble upon their own senescence, never having noticed that it was drawing nearer day by day.

quemadmodum aut sermo aut lectio aut aliqua intentior cogitatio iter facientis decipit et peruenisse ante sciunt quam appropinquasse, sic hoc iter vitae assiduum et citatissimum quod vigilantes dormientesque eodem gradu facimus occupatis non apparet nisi in fine.

The journey of life is just like a good conversation, an engrossing book, or a deep day-dream for a distracted traveller who suddenly finds themselves at the end of their journey - relentless and swift. It is a journey that we make at the same pace whether waking or sleeping. Those who undertake the journey while constantly preoccupied will only become aware of it at its very end.

X. in tria tempora vita dividitur: quod fuit, quod est, quod futurum est. ex his quod agimus breue est, quod acturi sumus dubium, quod egimus certum.

Life is divided into three acts — what has been, what is, and what shall be. Of these, the present time is short, and the future is doubtful. Only the past is certain.

hoc amittunt occupati; nec enim illis vacat praeterita respicere, et si vacet iniucunda est paenitendae rei recordatio.

People who are always preoccupied lose their sense of the past because they have no time to reflect on what has happened. Then, even if they do find the time to reflect, they discover that it is not pleasant to recall a past that must be viewed with regret.

XIV. soli omnium otiosi sunt qui sapientiae vacant, soli vivant.

Of everyone in the world, the only people who are truly at leisure are those who take time for philosophy.

They alone truly live!

Why outlive?

To some extent, drawing a contrast between Seneca and Attia is just extravagance on my part. But as I finished reading the book, in the epilogue in fact, I was pleased to find that Attia himself does ultimately acknowledge that his approach can become sterilised and obsessive when taken too far. He writes:

I had long subscribed to a kind of Silicon Valley approach to longevity and health, believing that it is possible to hack our biology, iteratiely, until we become perfect humanoids who can live to be 120 years old.

I used to be all about that, constantly tinkering and experimenting with new fasting protocols or sleep gadgets to maximise my own longevity. Everything in my life needed to be optimised. And longevity was basically an engineering problem…

My obsession with longevity was really about my fear of dying.

Perhaps the best place to end is with one of Attia’s own closing thoughts in the book:

The most important ingredient in the whole longevity equation is the why. Why do we want to live longer? For what? For whom?

I suspect that Seneca would very much approve of this conclusion. We can engineer and optimise our lives as much as we like, but ultimately we have to have an answer to the question: why? Why do we want to outlive? What will be the purpose of this additional time that we may have won for ourselves?

Thank you for reading and making it all the way to the end. As always, please reply if you have comments, questions or suggestions. Doubtless, I will have made many errors in this piece.

Please do not hesitate to reach out and I look forward to hearing from any of you that want to discuss this further.

Best wishes

Nick

Bibliography

Seneca’s De Brevitate Vitae

Latin Text, De Brevitate Vitae

English Text, On the Shortness of Life

Peter Attia’s Outlive

Outlive, 2023

Box Step Tutorial

Appendix: Attia’s tests for private patients

Computer tomography (CT) scan (for coronary calcifications, find % calcification of arteries).

Colonoscopy (to screen for bowel cancer from 40 years old, repeat every 2-3 years).

Full-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans (for glandular tumours in their early stages).

Uric acid level test (as an early warning sign for high blood pressure).

Glucose tolerance tests (to check for early signs of hyper-insulinemia, monitor homocysteine, chronic inflammation, triglyceride levels, and levels of very low density lipoprotein (VLDL)).

Bone density scan, known as a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) (annually to evaluate osteoporosis and to check their fat accumulation in and around visceral organs and in muscle tissue is very detrimental to metabolic health).

Apolipoprotein B (APOB) test (APOB is thought to be the main driver in atherosclerotic disease).

One-time test for Lp(a) genetics (if you carry certain versions of the Lp(a) gene, you may be at higher risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease).

Perhaps unfairly, I do not enjoy listening to Steven Bartlett. I note that this is a fairly consensus view that is espoused more eloquently elsewhere with criticisms typically levelled at him for being smug, more interested in the sound of his own voice than that of his interviewees, and unhealthily status conscious. Likewise, it seems to me that Bartlett frequently conflates worthwhile messages relating to well-being with pseudo-science and inanities. Whether this is intentional or not is difficult to say. Nonetheless, he and his team have produced a valuable episode in interviewing Peter Attia:

Cancer, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and dementia (along with several others), became collectively known as ‘diseases of civilisation,’ because they seemed to have spread in lockstep with the industrialisation and urbanisation of Europe and the United States. This does not mean that civilisation is somehow bad and that we all need to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. I would much rather live in our modern world, where I worry about losing my iPhone or missing a flight than endure the rampant disease, random violence, and lawlessness that our ancestors suffered through for millennia (and that people in some parts of our world still experience).

Attia: “For instance, fructose, long ago, consumed mainly in the form of fruit and honey, it enabled us to store energy as fat to survive cold winters and periods of scarcity. Now fructose is vastly overabundant in our diet, too much of it in liquid form, which disrupts our metabolism and our overall energy balance.”