The Periplus of Hanno the Navigator

Part 2: Carthaginian seafaring, the Heart of Darkness, and prehistoric West Africa

This piece explores the text known by scholars as ‘The Periplus of Hanno the Navigator’.

Strap in, dear reader, for this week’s instalment recounts an astonishing ancient tale. It will also be a longer read than others.

Today, I will cover the following:

Who was Hanno the Navigator?

What is a periplus?

What did Hanno see in ancient West Africa?

How did this text survive?

The Periplus of Hanno the Navigator

The manuscript starts as follows:

This is the account of the expedition of Hanno, the grand magistrate of the Carthaginians.

His expedition was to the Libyphoenician regions of the earth that lie beyond the Pillars of Herakles.

What follows is the account that he dedicated in the Temple of Baal-Hammon, which told the following story:

ΑΝΝΩΝΟΣ, ΚΑΡΧΗΔΟΝΙΩΝ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ, ΠΕΡΙΠΛΟΥΣ

ΤΩΝ ΥΠΕΡ ΤΑΣ ΗΡΑΚΛΕΟΥΣ ΣΤΗΛΑΣ ΛΙΒΥΚΩΝ ΤΗΣ ΓΗΣ ΜΕΡΩΝ

ὃν καὶ ἀνέθηκεν ἐν τῷ τοῦ Κρόνου τεμένει, δηλοῦντα τάδε.

Hanno the Navigator, Periplus

So the text begins, setting the scene for the reader. We learn that our protagonist will be Hanno, a magistrate who has been assigned the task of leading an expeditionary force to the west African coast by the Carthaginian state. We also discover that the source of this text is Hanno’s own account of the voyage that had been written down (perhaps on a stone or bronze tablet) and displayed at a great temple in Carthage.

An observation worth making straight away is that the text, as we find it preserved in our manuscript, is written in Greek, not Punic. If this tablet was hanging in a temple in Carthage, a Punic-speaking state, why on earth is it written in Greek?

The answer, straightforwardly, is that the original text was in fact Punic. The version preserved in our manuscript was almost certainly transcribed and translated from a Punic language tablet that hung in the temple. It was perhaps copied by a visiting Greek-speaking observer, probably a scribe of some sort. This act of transcription would have had to have taken place sometime prior to 146 BCE, the year in which the Temple of Baal-Hammon, along with all of Carthage, was levelled by the Romans.

Some attentive readers may have noticed that the phrase that I translate as ‘in the Temple of Ba’al Hammon’ in fact reads in the Greek as ‘in the Temple of Kronos’ (ἐν τῷ τοῦ Κρόνου τεμένει). Why have I substituted one god for another?

In the polytheistic pantheon of Greek religion, Kronos is the father of Zeus and progenitor of the Greek gods. With our limited knowledge of Punic religion, we can ascertain that the closest equivalent to Kronos would be Baal-Hammon. It seems very unlikely that there would have been a temple to Kronos, a Greek deity, in Carthage. But we know from archaeological sources that there most certainly was a temple to Baal-Hammon in Carthage. The corresponding Roman deity is Saturn.

Thus, the Greek scribe appears to have made another substitution. The scribe has amalgamated an understanding of Punic religion with Greek religion, perhaps to make the text more comprehensible to a Greek-speaking audience. This is not at all unusual. Indeed, throughout the Greco-Roman world, the assimilation of discrete religious or cultural traditions into a single figure or narrative, was commonplace.1

The substitution of Carthaginian concepts for Greek ones recurs throughout the text. In fact, in the very first line of our manuscript it happens again. Here, Hanno is referred to in the Greek as a basileus (βασιλεύς). This term is a Greek political concept, often used to describe tyrannical or oligarchical rulers. Typically, we would translate it as ‘king’. However, even from our limited knowledge of Carthaginian socio-political life, we know that there was no hereditary monarchy in Carthage in the era during which Hanno most likely lived (around 600-500 BCE). At that time, Carthage was an oligarchical republic and its rulers were elected annually and non-hereditary, roughly analogous to Roman consuls. I attempt to capture this in my translation ‘grand magistrate’.

In Punic, the rank of ruling magistrate was known as suffes, so perhaps ‘suffes’ would have been a satisfactory rendering. The suffes, a community leader of significant civic stature, is a political concept familiar to several ancient Semitic cultures and associated historical regions, also known as shopheṭ or shofeṭ (Hebrew: שׁוֹפֵט šōfēṭ, Phoenician: 𐤔𐤐𐤈 šōfēṭ, Punic: 𐤔𐤐𐤈 šūfeṭ). In Hebrew, shopheṭ literally means ‘judge’. See, for instance, the Old Testament’s ‘Book of Judges’ (ספר שופטים, Sefer Shoftim).

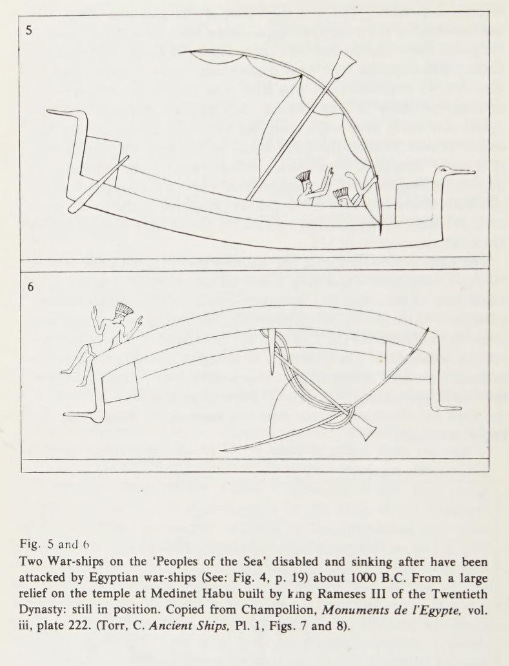

One final note on this opening passage. What I translate as ‘the account of the expedition’, is a single world in Greek, peri-plous (περίπλους). A periplus or periplous literally means ‘a sailing-around’, referring specifically to the navigational record kept by a ship’s captain. Take, for instance, ‘The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea’, a navigational guide written by a Greek-speaking Egyptian merchant at the edges of the Roman world in the 1st-century CE describing the coastlines of the Red Sea, Arabian Sea, and the Horn of Africa.

Similarly, Hanno’s periplus is a navigational guide. It contains frequent references to the distances sailed and the names of trading posts. Unlike many peripluses, however, Hanno’s account offers a narrative rich in descriptive and anecdotal detail. Indeed, Hanno’s remarkable text represents the only known first-hand description of the western part of the continent of Africa until the accounts of the Portuguese in the 1400s CE.

As we shall see, Hanno has a fascinating story to tell. Along the way, his naval convoy visits unknown lands, escapes from hostile locals, encounters native wild animals, and witnesses volcanic activity…

Departure from Carthage

At that time, it pleased the Carthaginians that Hanno should sail beyond the Pillars of Herakles and establish a number of Libyphoenician cities.

So, Hanno set sail with sixty fifty-oared ships, a multitude of men and women, in the order of thirty thousand, with food and other provisions.

Ἔδοξε Καρχηδονίοις Ἅννωνα πλεῖν ἔξω Στηλῶν Ἡρακλείων καὶ πόλεις κτίζειν Λιβυφοινίκων.

καὶ ἔπλευσε πεντηκοντόρους ἑξήκοντα ἄγων, καὶ πλῆθος ἀνδρῶν καὶ γυναικῶν εἰς ἀριθμὸν μυριάδων τριῶν καὶ σῖτα καὶ τὴν ἄλλην παρασκευήν.

Hanno the Navigator, Periplus

Here, the text explains that Hanno set sail from Carthage westwards, out towards the ‘Pillars of Herakles’ (Στηλῶν Ἡρακλείων), our modern-day Straits of Gibraltar.

Hanno’s mission was to explore the northwestern coast of Africa and to establish ‘Libyphoenician cities’. Libya here should be understood as synonymous with our word Africa, rather than referring to the modern-day nation state known as Libya. Likewise, we should understand Libyphoenicians as people of Phoenician origin that live in Africa.

The tablet also suggests that Carthage dispatched Hanno at the head of a fleet of 60 ships and that his ships were filled with 30,000 people who would colonise, populate, or repopulate the aforementioned Libyphoenician outposts and settlements on the northwestern coast of Africa.

At this point, it is worth flagging three additional caveats, then I promise we will speed up with the narrative itself.

First, we must be wary of unintentional scribal errors. The number of voyagers suggested here, 30,000, is extraordinarily large, not only in absolute terms, but also in practical terms. Loading that quantity of settlers into a mere 60 ships would be an impressive feat of engineering in the ancient world. That is by no means to say that it is not possible that there were 30,000 passengers, but it is certainly a suspect claim. Numbers are easily corrupted in textual transmission. For example, later in the text, scholars are fairly confident that the number ‘twelve’ has been corrupted to ‘two’ (used in relation to the number of days’ voyage along the desert coast). This would be a straightforward scribal error (writing B' instead of IB') and one that is commonly seen in manuscripts. How many other transmission errors and scribal corruptions might have crept into the text in the intervening codices between our manuscript and the original that was made by the Greek scribe in Carthage?

Second, intentional scribal edits. We have already seen how our Greek scribe can take a very liberal approach to substituting key words. Might it also be reasonable to infer that, in producing this document, the scribe has abridged or summarised sections of a longer original document? Given the limited contextual evidence with which we are working, it is impossible to know the answers to any of these questions for certain. My view is that we must simply bear in mind these risks and take everything we read with a healthy dose of scepticism as we attempt to reconstruct Hanno’s journey.

Third, how do we even know that this account is true at all? Could it simply be invented or fictitious? The short answer is that we do not know. Nonetheless, personally, I am confident that this manuscript is based on a first-hand account, most likely Hanno’s original account of a real journey. Throughout the text, the narrator describes west African locations and species with accuracy. Moreover, many ancient authors, even rough contemporaries like Herodotus, had heard of Hanno’s exploits and recorded them (see Appendix II). Perhaps most importantly of all, we know that, during this period of Carthaginian history, Carthage was steadily increasing its power and domain, expanding outwards and seeking new trade opportunities. Another Carthaginian magistrate, Himilco, was believed to have set off at the same time as Hanno to explore the seas north of the Pillars of Herakles towards the British Isles. Pliny the Elder, who knew of both, writes:

When the power of Carthage flourished, Hanno sailed round from Cádiz to the extremity of Arabia, and published a memoir of his voyage, as did Himilco when he was dispatched at the same date to explore the outer coasts of Europe

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 2.169a.

So, we have completed our analysis of the text’s opening notes. Let’s now dive properly into Hanno’s first-person account of the voyage, his periplus.

Colonising Libyphoenicia

After sailing beyond the Pillars for two days, we founded our first city, called Thymiaterion. Below it was a large plain.

Continuing our voyage from there, we reached the Lixus, a large river flowing from Libya. The Lixites, a nomadic tribe, were pasturing their cattle beside it. We remained with them for some time and became friends.

When we had got interpreters from the Lixites, we sailed along the desert shore for two days to the south.

Ὡς δ᾽ ἀναχθέντες τὰς Στήλας παρημείψαμεν καὶ ἔξω πλοῦν δυοῖν ἡμερῶν ἐπλεύσαμεν, ἐκτίσαμεν πρώτην πόλιν, ἥντινα ὠνομάσαμεν Θυμιατήριον· πεδίον δ᾽ αὐτῇ μέγα ὑπῆν.

Κἀκεῖθεν δ᾽ ἀναχθέντες ἤλθομεν ἐπὶ μέγαν ποταμὸν Λίξον, ἀπὸ τῆς Λιβύης ῥέοντα. Παρὰ δ᾽ αὐτὸν νομάδες ἄνθρωποι Λιξῖται βοσκήματ᾽ ἔνεμον, παρ᾽ οἷς ἐμείναμεν ἄχρι τινὸς φίλοι γενόμενοι.

Λαβόντες δὲ παρ᾽ αὐτῶν ἑρμηνέας, παρεπλέομεν τὴν ἐρήμην πρὸς μεσημβρίαν δύο ἡμέρας·

Hanno the Navigator, Periplus

We have established that Hanno began the expedition by sailing his fleet beyond the mouth of the Mediterranean Sea, through the Straits of Gibraltar, and along the north-west coast of Africa. In doing so, Hanno took his ships from the well-known trading routes of the western Mediterranean into relatively uncharted waters out in the Atlantic ocean.

Sticking close to the Atlantic coast of the continent, Hanno’s ships then made landfall at various points. At these landing sites, Hanno’s passengers disembarked and set up cities or trading posts, populating seven colonies in total along the coast of modern-day Morocco.

Unsurprisingly, in establishing these trading posts, Hanno’s contingent came into contact with the local people who already lived in those lands. These locals are referred to as ‘Lixites’ in the text. Scholars hypothesise that they were most likely a Berber people with whom the Carthaginians were able to communicate. Given that the Carthaginians were a seafaring and mercantile civilisation, it seems very likely that they established these settlements for the very purpose of making contact with the local Lixites in order to connect them into the broader network of Phoenician trade.

Here too, we learn that the Lixites played an important role in the second act of Hanno’s expedition. Hanno informs us that the Lixites were able to provide interpreters to him who could communicate with the inhabitants of more distant sections of the African coast.

So, Hanno embarked on the next stage of his mission, to sail and explore further round the African coast than any Carthaginian had ever previously attempted.

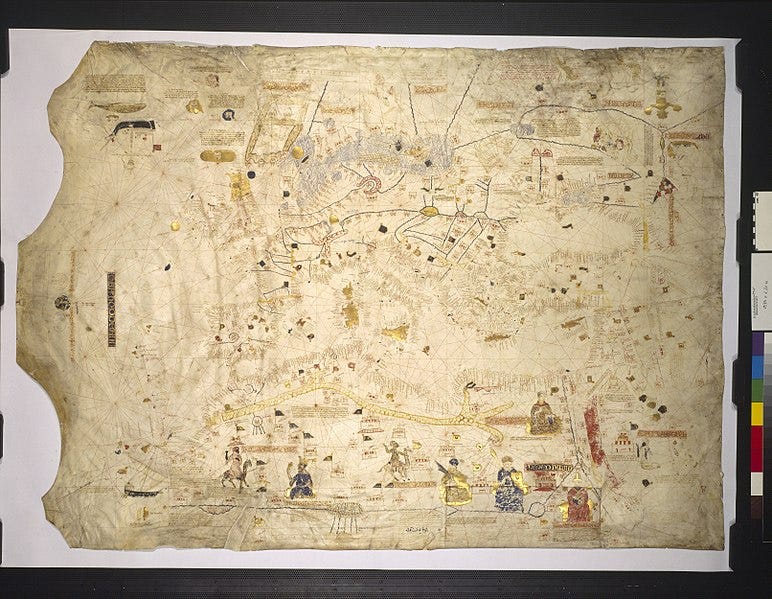

Charting the Journey into the Unknown

Here is an attempted reconstruction of Hanno’s journey using the measurements from the periplus and a modern map. Since these lands were previously unknown to Carthaginians (and still relatively unknown visited afterwards), the names and geographical markers referenced in the text are difficult to locate today with any certainty.

From my reading of the text and scholars’ analysis of the comparative archaeological evidence, I am confident that the above reconstruction is an accurate representation of Hanno’s voyage. But, as ever, there is no definitive way to ascertain the route and every step of the route is debatable.

For this reason, I offer an alternative reconstruction of Hanno’s route below for comparison to demonstrate to readers just how widely scholars’ estimations vary.

For the remainder of this piece I shall not delay us further with caveats around textual transmission and precision. Let’s simply enjoy the story as we have it for what it’s worth.

Aethiopians & Troglodytes

For Hanno and his fleet, the voyage along the coast of Africa took them to lands as yet ‘undiscovered’.

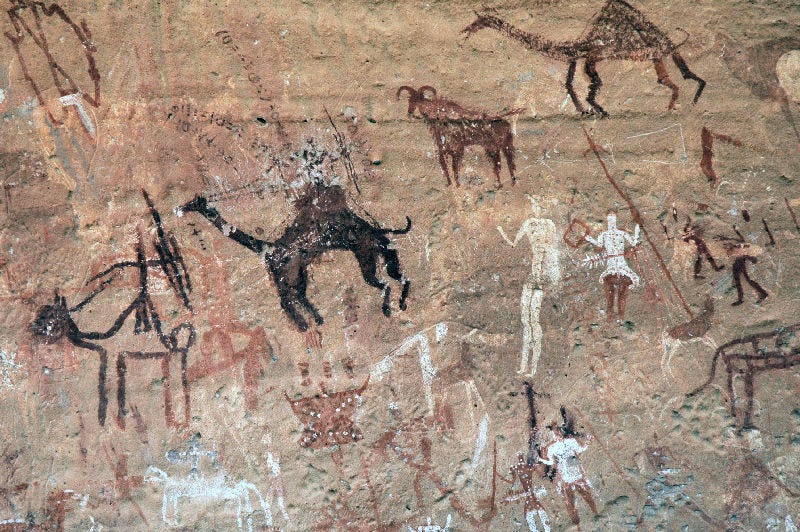

But, of course, these lands were already inhabited. In fact, West Africa had been continuously inhabited since almost the very dawn of humanity itself. Our oldest known evidence for anatomically modern humans (as of 2023) are fossils found at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, dated to about 360,000 years old.2

As the fleet sailed southwards, Hanno fascinatingly describes some of the local inhabitants of the coast of West Africa encountered by his expeditionary force:

Beyond [the Lixites] lived hostile Aethiopians (Αἰθίοπες), occupying a land full of wild animals. That land was surrounded by great mountains whence flows a river known as the Lixus.

The Lixites say that a people dwell among these mountains who are different in physical appearance: the cave people (Τρωγλοδύτας), who run faster than horses.

Τούτων δὲ καθύπερθεν Αἰθίοπες ᾤκουν ἄξενοι, γῆν νεμόμενοι θηριώδη, διειλημμένην ὄρεσι μεγάλοις, ἐξ ὧν ῥεῖν φασι τὸν Λίξον,

περὶ δὲ τὰ ὄρη κατοικεῖν ἀνθρώπους ἀλλοιομόρφους, Τρωγλοδύτας· οὓς ταχυτέρος ἵππων ἐν δρόμοις ἔφραζον οἱ Λιξῖται.

Hanno the Navigator, Periplus

We arrived at the end of the bay which was overhung by some very great mountains. The bay was filled with hostile locals who were clad in animals' skins. By throwing stones, these people prevented us from disembarking and drove us away.

From there, we sailed to the south for twelve days. We remained close to the coast, which was entirely inhabited by Aethiopians, who fled from us when we approached. Even to our Lixites, their language was unintelligible.

Ἀφ᾽ ὧν ἡμερήσιον πλοῦν κατανύσαντες εἰς τὸν μυχὸν τῆς λίμνης ἤλθομεν, ὑπὲρ ἣν ὄρη μέγιστα ὑπερέτεινε, μεστὰ ἀνθρώπων ἀγρίων, δέρματα θήρεια ἐνημμένων, οἳ πέτροις βάλλοντες ἀπήραξαν ἡμᾶς, κωλύοντες ἐκβῆναι.

Ἐκεῖθεν δὲ ἐπὶ μεσημβρίαν ἐπλεύσαμεν δώδεκα ἡμέρας, τὴν γῆν παραλεγόμενοι, ἣν πᾶσαν κατῴκουν Αἰθίοπες φεύγοντες ἡμᾶς καὶ οὐχ ὑπομένοντες· ἀσύνετα δ᾽ ἐφθέγγοντο καὶ τοῖς μεθ᾽ ἡμῶν Λιξίταις.

Hanno the Navigator, Periplus

This very high-level anthropological commentary provided by Hanno offers us tantalising glimpses into the world of ancient West Africa and the lives of those people into whose realm he and his expedition had voyaged.

It is worth clarifying a few points. As with the term ‘Libya’ above, the use of the term ‘Aethiopian’ should not be mistaken for our modern-day demonym for the inhabitants of the geographical area and state known as Ethiopia. Although etymologically the same, the term ‘Aethiopian’ (note that I translate the word with an ‘A’ to differentiate the terms), is derived from the Greek meaning ‘burnt face’. Throughout ancient Greek literature, this term is commonly used to refer to any indigenous African peoples with darker skin pigmentation. In the same way that one might indiscriminately refer to many different peoples, communities, and cultures today using a single demonym like ‘European’, ‘Indian’, or ‘African’, Aethiopian could be understood as a similarly imprecise term in the ancient Greek lexicon. In other words, the term might equally be used by a Greek to describe an inhabitant of East Africa or an inhabitant of West Africa without offering any specific insight into the identity of the cultural or ethnic group in question.

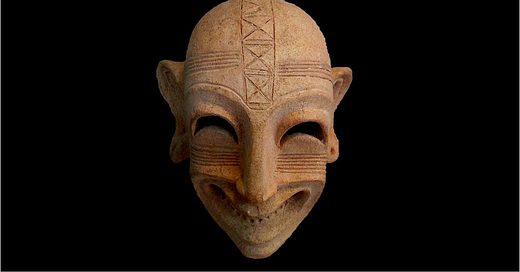

Here, we might understand ‘Aethiopian’ as referring to, (i) in the first quoted passage, a non-Berber community in the Mauretanian region (perhaps Khoisan? further detail below) and (ii) in the second quoted passage, a Kru-culture people inhabiting an area near modern-day Senegal. The latter identification is perhaps confirmed when Hanno remarks that his Lixite translators were unable to communicate with the native population once they entered the regions below the island of Kerne (from Phoenician chernah, which means ‘last habitation’, most likely modern-day Ad Dhakla, Morocco). This would be the region where Kru languages were historically spoken.

The ‘cave-dwellers’ (Greek: τρωγλοδύται, troglodytes) that Hanno records are an even more inscrutable historical people. So-called ‘cave-dwellers’ potentially are an archaeologically and culturally distinguishable group of people. We often see them referenced in other ancient sources too, such as in Herodotus’ work. Like Hanno, Herodotus reports that the cave-dwellers were ‘swifter than all other men’ (τάχιστοι ἀνθρώπων πάντων).

Hanno associates the cave-dwellers with the epithet ἄξενοι ‘unfriendly’ or ‘inhospitable’, literally, ‘unwelcoming to guests’. On reading Herodotus, however, it seems that the cave-dwellers likely had very good reasons for being unwelcoming to guests. Herodotus reports that the Garamantes, a neighbouring pastoralist Berber people from modern-day Libya, literally hunted down cave-dwellers using chariots.

The Garamantes go in their four-horse chariots chasing the cave-dwelling Aethiopians (τρωγλοδύται Αἰθίοπες) . For the Aethiopian cave-dwellers are swifter of foot than any men of whom tales are brought to us.

They live on snakes and lizards and such-like creeping things. Their speech is like no other in the world: it is like the squeaking of bats.

οἱ Γαράμαντες δὴ οὗτοι τοὺς τρωγλοδύτας Αἰθίοπας θηρεύουσι τοῖσι τεθρίπποισι. οἱ γὰρ τρωγλοδύται Αἰθίοπες πόδας τάχιστοι ἀνθρώπων πάντων εἰσὶ τῶν ἡμεῖς πέρι λόγους ἀποφερομένους ἀκούομεν.

σιτέονται δὲ οἱ τρωγλοδύται ὄφις καὶ σαύρους καὶ τὰ τοιαῦτα τῶν ἑρπετῶν: γλῶσσαν δὲ οὐδεμιῇ ἄλλῃ παρομοίην νενομίκασι, ἀλλὰ τετρίγασι κατά περ αἱ νυκτερίδες.

Herodotus, Histories 4.183

Compare too references in Strabo, Geography 16.4.7; Diodorus, World History 3.32-33. Eusebius, citing Clement of Alexandria, claimed that they invented the sambuca instrument Preparation of the Gospels 10.6.1.

Given this eclectic mix of ancient sources, what can we say for sure?

Well, it seems that both Hanno and Herodotus are describing a group of people that occupy cave-like inhabitations in the north African deserts. Archaeologists have identified a number of prehistoric sites that were the homes of nomadic peoples in these desert regions. These nomads would occasionally seek shelter, often in the form of cave shelter, as a base from which to source water, find shade at the hottest times of year, and procure food. Beehives and nests, for example, have been attested at these sites amongst the archaeological material culture.

Herodotus’ remark about the language of the cave-dwellers is particularly striking (echoed by Pomponius Mela, Chorographia, 1.44 strident magis quam locuntur ‘they make shrill noises more than they speak’). A 19th-century Austrian-British scholar of Bantu and Khoekhoen languages, Alice Werner, identified Herodotus’ description of ‘speech like the squeaking of bats’ with the distinctive click sounds of Khoisan languages. She hypothesises that these people may have been an early Khoisan culture, whose cultural descendants can still be found amongst indigenous inhabitants of Southern Africa.3

Rainforests, Rivers, & Gold

As Hanno’s fleet continued its progress along the coast, it traversed the coastal desert region to reach the great rivers, lakes, and mountains of the rainforested part of West Africa.

We reached a lake, it was not far from the sea and was covered with many long reeds, from which elephants and other wild animals were eating.

Leaving from there, we arrived at another large, broad river teeming with crocodiles and hippopotamuses.

We anchored by some tall mountains. They were covered with trees whose wood was aromatic and colourful.

ἄχρι ἐκομίσθημεν εἰς λίμνην οὐ πόῤῥω τῆς θαλάττης κειμένην, καλάμου μεστὴν πολλοῦ καὶ μεγάλου· ἐνῆσαν δὲ καὶ ἐλέφαντες καὶ τἆλλα θηρία νεμόμενα πάμπολλα.

Ἐκεῖθεν πλέοντες εἰς ἕτερον ἤλθομεν ποταμὸν μέγαν καὶ πλατύν, γέμοντα κροκοδείλων καὶ ἵππων ποταμίων.

Τῇ δ᾽ οὖν τελευταίᾳ ἡμέρᾳ προσωρμίσθημεν ὄρεσι μεγάλοις δασέσιν. Ἦν δὲ τὰ τῶν δένδρων ξύλα εὐώδη τε καὶ ποικίλα.

Hanno the Navigator, Periplus

Here, I quote the text out of order to gather together all the relevant passages that comment on the region’s natural history.

Elephants, hippopotamus, and crocodiles - Hanno’s boats encountered a broad range of indigenous wild animals as they stopped to take on water at the mouths of river deltas or in protective bays.

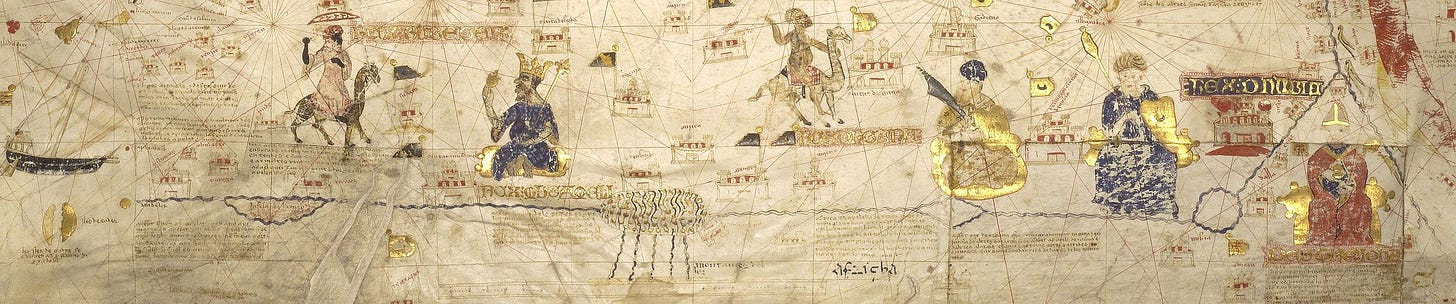

Of particular note, perhaps, is the fact that scholars identify Hanno’s ‘large broad river’ with the River Senegal. Upstream of the Senegal delta is the gold-bearing region of Bambouk. In the 13th-century CE, this same region would be home to the famed Mansa Musa, king of the Mali Empire.

Does this offer us a clue as to the real purpose of Hanno’s onwards expedition? Might Hanno’s voyagers have obtained precious metals at the delta of this river? It is striking that gold is not mentioned once throughout the text. Is its omission intentional? The only intimations that hint towards this are the narrator’s peculiar interest in the ‘aromatic and colourful’ species of tree he encounters.

It seems to me that, with the ever-savvy commerciality of merchant seafarers, the Carthaginians wereon the look-out for profitable trading opportunities. The river Senegal was, after all, known by traders for many centuries after as the ‘river of gold’. Equally, however, it would also be very commercially-minded of the Carthaginians to protect their proprietary trade routes and exclusive suppliers.

Should we speculate that the Carthaginians either (i) chose not publish their trade secrets on the tablet to hide them from rivals or (ii) did not permit the Greek scribe to include them in the translation? Was the real purpose of Hanno’s onwards expedition to search for the gold of Bambouk and other riches? The search for El Dorado or King Solomon’s Mines as it were.

Into the Heart of Darkness

Time and again, in translating Hanno’s account, I found myself marvelling at the familiarity of the descriptions. Surely, I thought, I have read this very same account of West Africa by a visitor on a ship somewhere else.

As I called to mind the familiar words and phrases, it struck me - it was Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’, a text written more than two millenia after Hanno lived. Might a brief comparative analysis of passages from the respective texts provoke some further stimulation?

In broad terms, Conrad’s text is similar to Hanno’s. In the detail too, we quickly find commonalities. For instance, when Conrad’s narrator describes the flora and fauna along the River Congo delta, those passages are reminiscent of the Carthaginian account:

Trees, trees, millions of trees, massive, immense, running up high; and at their foot, hugging the bank against the stream, crept the little begrimed steamboat.

On silvery sand-banks hippos and alligators sunned themselves side by side. The broadening waters flowed through a mob of wooded islands; you lost your way on that river as you would in a desert, and butted all day long against shoals, trying to find the channel, till you thought yourself bewitched and cut off for ever from everything you had known once—somewhere—far away—in another existence perhaps

Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad (1899)

Admittedly, Conrad’s description is more detailed and elaborate than Hanno's. Given, however, that Conrad was writing outside of the constraints of a bronze tablet, it is perhaps unsurprising that his text offers us a richer set of visual vignettes.

Most striking of all to me, was the following pair of passages.

Hanno:

Here we disembarked. In daytime, we could see nothing but the forest, but during the night, we noticed many fires alight and heard the far-off beating of cymbals and drums and the shouts of a multitude.

Quickly and in fear, we sailed away…

εἰς ἣν ἀποβάντες ἡμέρας μὲν οὐδὲν ἀφεωρῶμεν ὅτι μὴ ὕλην, νυκτὸς δὲ πυρά τε πολλὰ καιόμενα, καὶ φωνὴν αὐλῶν ἠκούομεν κυμβάλων τε καὶ τυμπάνων πάταγον καὶ κραυγὴν μυρίαν.

Φόβος οὖν ἔλαβεν ἡμᾶς, καὶ οἱ μάντεις ἐκέλευον ἐκλείπειν…

Hanno the Navigator, Periplus

Conrad:

Perhaps on some quiet night the tremor of far-off drums, sinking, swelling, a tremor vast, faint; a sound weird, appealing, suggestive, and wild—and perhaps with as profound a meaning as the sound of bells in a Christian country…

We penetrated deeper and deeper into the heart of darkness. It was very quiet there. At night sometimes the roll of drums behind the curtain of trees would run up the river and remain sustained faintly, as if hovering in the air high over our heads, till the first break of day. Whether it meant war, peace, or prayer we could not tell…

The wild crowd of obedient worshippers, the gloom of the forests, the glitter of the reach between the murky bends, the beat of the drum, regular and muffled like the beating of a heart—the heart of a conquering darkness. It was a moment of triumph for the wilderness, an invading and vengeful rush… at my back the fires loomed between the trees, and the murmur of many voices issued from the forest

Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad (1899)

To my ear, the parallels are simply astonishing. That such similar experiences could be had by voyagers arriving by ship more than 2,000 years apart seems singularly remarkable. So many specific details match: the description of the fires in the forest; the setting during the night-time; and the references to far-off voices and drums.

Is the sheer extent of the resemblance is perhaps further confirmation of the validity of Hanno’s text? Or is it the case that Conrad’s text is somehow informed by Hanno’s? Could Hanno’s imagery have seeped through literary culture for 2,000 years or could Conrad himself have read the text (or at least some analysis of it)?

Personally, given the fact that the Carthaginian text is so recondite and under-studied, I think it is singularly unlikely that Conrad ever encountered Hanno’s periplus.

The Seat of the Gods

Hanno’s expedition had now begun to approach the equatorial region of the African continent. Here, Hanno bore witness to unfamiliar geological activity:

We passed along a fiery coast full of incense. Large torrents of fire emptied into the sea, and the land was inaccessible because of the heat.

Quickly and in fear, we sailed away from that place. Sailing on for four days, we saw the coast by night full of flames. In the middle was a big flame, taller than the others and apparently rising to the stars. By day, this turned out to be a very high mountain, which was called Chariot of the Gods.

Sailing thence along the torrents of fire, we arrived after three days at a bay called Horn of the South.

παρημειβόμεθα χώραν διάπυρον θυμιαμάτων μεστ[ήν· μέγιστ]οι δ᾽ ἀπ᾽ αὐτῆς πυρώδεις ῥύακες ἐνέβαλλον εἰς τὴν θάλατταν. Ἡ γῆ δ᾽ ὑπὸ θέρμης ἄβατος ἦν.

Ταχὺ οὖν κἀκεῖθεν φοβηθέντες ἀπεπλεύσαμεν. Τέτταρας δ᾽ ἡμέρας φερόμενοι νυκτὸς τὴν γῆν ἀφεωρῶμεν φλογὸς μεστήν· ἐν μέσῳ δ᾽ ἦν ἠλίβατόν τι πῦρ, τῶν ἄλλων μεῖζον, ἁπτόμενον ὡς ἐδόκει τῶν ἄστρων. Τοῦτο δ᾽ ἡμέρας ὄρος ἐφαίνετο μέγιστον, Θεῶν ὄχημα καλούμενον.

Τριταῖοι δ᾽ ἐκεῖθεν πυρώδεις ῥύακας παραπλεύσαντες ἀφικόμεθα εἰς κόλπον Νότου Κέρας λεγόμενον.

Hanno the Navigator, Periplus

Evidently, Hanno and his crew were witnessing volcanic activity. But where was this volcanic mountain known to Hanno’s interpreters as the ‘Chariot of the Gods’ (Θεῶν ὄχημα)?

Some scholars have connected this volcano with Kakulima mountain in Guinea, an identification that would considerably shorten Hanno's voyage. That volcano, however, does not appear to have been active since a very long time before Hanno’s lifetime.

A much more compelling identification for this mountain would be with Mount Cameroon. We know that in 1922, for instance, the lava of Mount Cameroon poured into the sea. Moreover, in Bakweri, the local Bantu language of the coastal Cameroonian Kwe peoples, the name for the mountain happens to be Mongo-mo-Ndemi ‘Seat of the Gods’ (the highest point of the volcanic peak is known as Monga-ma-Loba, ‘Seat of Thunder’). In Greek, the word for seat or throne would be οἴκημα. With our knowledge of the trials and tribulations of textual transmission, we can appreciate that it is no great leap for a scribe copying the text to accidentally corrupt the word οἴκημα ‘seat’ to ὄχημα ‘chariot’.

Out of interest, compare this passage of Conrad:

Flames glided in the river, small green flames, red flames, white flames, pursuing, overtaking, joining, crossing each other—then separating slowly or hastily.

Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad (1899)

Finally… Gorillas

Having survived their encounter with the volcano, Hanno and his fleet now reached the final stages of their voyage.

In this closing chapter of his tale, Hanno tells one final anecdote that suitably caps off the whole remarkable journey:

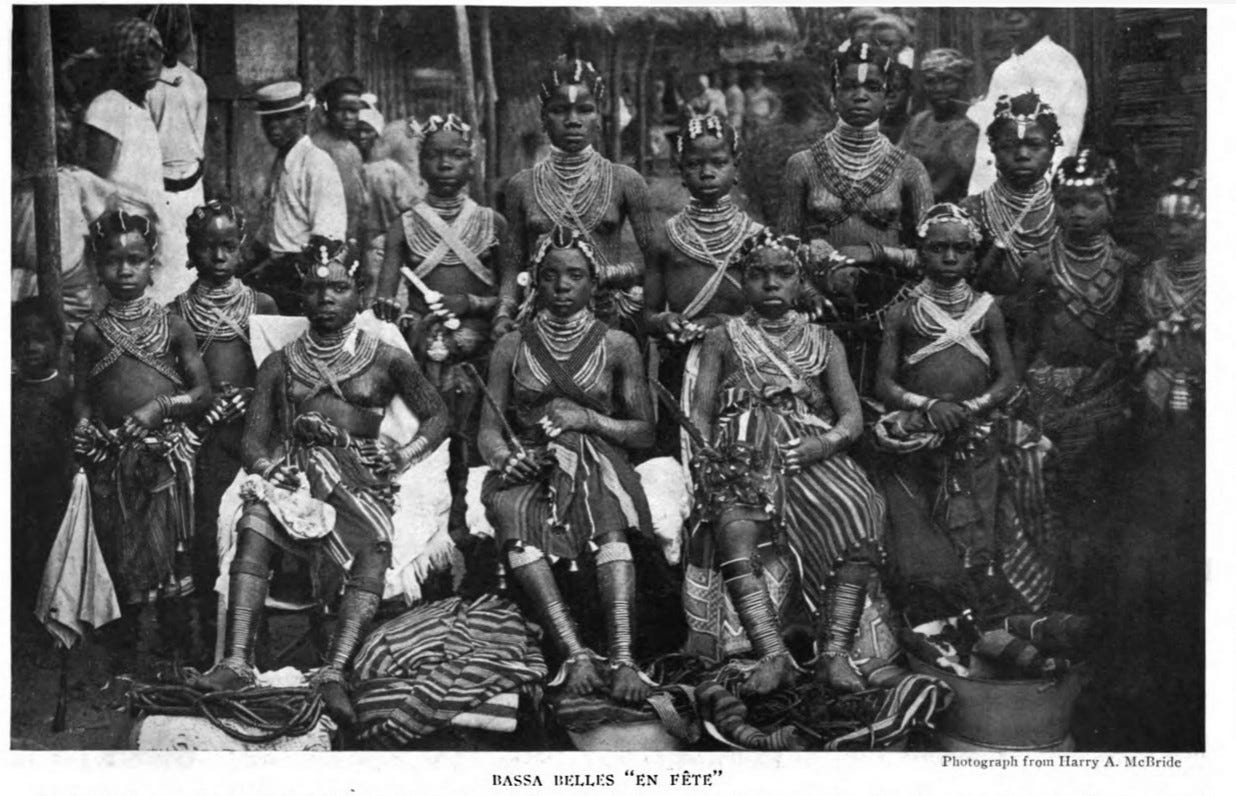

In this gulf was an island, resembling the first, with a lagoon, within which was another island, full of hostile people.

Most of them were women with hairy bodies, whom our interpreters called ‘gorillas’ (Γοριλλαι).

Although we chased them, we could not catch any males: they all escaped, being good climbers who defended themselves with stones. However, we caught three women, who refused to follow those who carried them off, biting and clawing them.

So we killed and flayed them and brought their skins back to Carthage.

Ἐν δὲ τῷ μυχῷ νῆσος ἦν, ἐοικυῖα τῇ πρώτῃ, λίμνην ἔχουσα· καὶ ἐν ταύτῃ νῆσος ἦν ἑτέρα, μεστὴ ἀνθρώπων ἀγρίων.

Πολὺ δὲ πλείους ἦσαν γυναῖκες, δασεῖαι τοῖς σώμασιν· ἃς οἱ ἑρμηνέες ἐκάλουν Γορίλλας.

Διώκοντες δὲ ἄνδρας μὲν συλλαβεῖν οὐκ ἠδυνήθημεν, ἀλλὰ πάντες (μὲν) ἐξέφυγον, κρημνοβάται ὄντες καὶ τοῖς πέτροις ἀμυνόμενοι, γυναῖκας δὲ τρεῖς, αἳ δάκνουσαί τε καὶ σπαράττουσαι τοὺς ἄγοντας οὐκ ἤθελον ἕπεσθαι.

Ἀποκτείναντες μέντοι αὐτὰς ἐξεδείραμεν καὶ τὰς δορὰς ἐκομίσαμεν εἰς Καρχηδόνα.

Hanno the Navigator, Periplus

Two immediate responses spring to my mind in reading this final passage.

First, Hanno’s mission report up to this point has been largely peaceful and mercantile in nature. As a result, this abrupt and brutal end is somewhat unexpected, standing in stark contrast to the rest of the account. An ancient reader, more accustomed to everyday brutality, would most likely be less perturbed by the account. But even so, the flaying of victims is a particularly horrifying practice, although in this case presumably employed for the purpose of collecting specimens rather than for torture.

For me, this is a reminder that, at its worst, humanity can inflict cruelty and brutality. There are manifold similarities between our own time and Hanno’s time. Gorillas are treated appallingly by people today and humans are still brutalised and mistreated by other humans too. This, of course, has held true all through our species’ history. Invariably, humans have at times suffered, whether at the hands of neighbours or outsiders. One can only hope that, as Stephen Pinker argues, The Better Angels of Our Nature will persevere and violence will continue to decline structurally across time and place (Pinker, 2011).

My second reaction to this passage is - blimey, did they really find gorillas!

Once again, one cannot be sure. Could they instead be some sort of indigenous people? Could they even be another species of the homo genus, now lost, equivalent to a homo neanderthalensis or homo floresiensis? Probably not. On balance, by far the most plausible explanation is that these were indeed gorillas or another species of Great Ape. The Roman author Pliny the Elder records that the furs of the ‘Gorillas’ were exhibited in the temple of the goddess Tanit until Carthage was destroyed by the Romans (Natural History 6.200).

I read in one commentary that in a Bantu language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, kiKongo, the words ngò dìida, which transliterates to ‘gorilla’, means ‘powerful animal that beats itself violently’, which would convey nicely the gorilla's characteristic drumming on the chest. Another commentary tells me that it means ‘hairy person’, again convincingly gorilla-sounding. Here, I must admit, my meagre knowledge of Bantu languages fails me.

The nature of the etymology eludes me too. I assume our word ‘gorilla’ comes from the kiKongo language directly rather than via the Greek of Hanno’s text, but again I have yet to see definitive evidence of this in my readings.

In any case, given that we still find the word gorilla in languages native to the region today, the use of the word in the text is very supportive of the case arguing that Hanno really did voyage as far as the River Congo and the equator (indeed, as far as Joseph Conrad journeyed many centuries later).

We did not sail any further, because our provisions were running short.

Οὐ γὰρ ἔτι ἐπλεύσαμεν προσωτέρω, τῶν σίτων ἡμᾶς ἐπιλιπόντων.

Hanno the Navigator, Periplus

With that, Hanno ends his extraordinary account of the expeditionary voyage. And with the dedication of the flayed gorilla skins in a temple, we find ourselves right back where we began, in Carthage.

Conclusion

Thank you so much for reading all the way to the end.

This one took longer than usual, hence the delayed publication, but I hope it was enjoyable and worth the wait.

If your interest is not sated, read on below to learn about the equally gripping history of the manuscript codex’s transmission and the appearances of Hanno in other ancient texts.

Above all else, I hope that you will agree that Hanno’s story is extraordinary and that his rollicking adventures offer us a unique glimpse into the world of the ancient Carthaginians and West Africa in the 5th-century BC.

Bibliography

Hanno's text was first edited for print publication by Sigismund Gelenius in Basel around 1533.

The text was first translated into English by Wilfred Schott and published as The Periplus of Hanno. A Voyage of Discovery Down the West African Coast by a Carthaginian Admiral of the Fifth Century B.C. (1912).

My key sources were:

Off the Beaten Track in the Classics, Carl Kaeppel (1936)

Commentary, G. Kluge (1829)

Commentary, Livius, Jona Lendering (2020)

Cave-Dwelling Peoples, Livius (2020)

Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad (1899)

The Edges of the World in Ancient Thought: Geography, Exploration, and Fiction, James Romm (1992)

Note to self - track down a copy of this next time at British Library:

Palmer, H. R. “The Lixitae of Hanno.” Journal of the Royal African Society, Vo. 27, No. 105 (Oct., 1927), pp. 7-15.

The Full Text

Reading the varied and complex notation employed by manuscript scribes can be troublesome. For the benefit of readers who wish to read directly from the codex, I share here a full transcription and translation of the manuscript, which can be difficult to obtain.

Appendix I: The Manuscript, Palatinus Graecus 398

This is an account of the remarkable history of the preservation of Palatinus 398, the single manuscript codex containing Hanno’s account to have survived the intervening centuries of hazardous textual transmission.

Here, in full, I reproduce the three leaves of manuscript from the codex that contain the text in its sole surviving copy:

This manuscript belongs to the University of Heidelberg and is known as the Codex Heidelbergensis Palatinus Graecus 398. This codex is truly mirabile visu - a marvel to behold. It consists of a number of unique texts, each meriting their own separate analysis and discussion. In total, codex contains 321 well-preserved parchment leaves.

Our knowledge of the manuscript’s history begins with Cardinal John Stojković of Ragusa. This chap was a papal theologian and legate of the General Council of the Roman Catholic Church that convened at Basel in 1431.

Following the papal council, Cardinal John was commissioned by Pope Eugenius IV and the Council to journey across the Mediterranean to Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, the seat of Greek Orthodoxy, and headquarters of the Eastern Catholic Churches.

In Constantinople, John was to make the case for the reunion of the Eastern and Western Churches in his capacity as the council’s legate by petitioning the Byzantine Emperor John VIII Paleologus and the Ecumenical Patriarch Joseph II of Constantinople.

Unfortunately, John’s trip was entirely unproductive politically speaking. But, being a diligent fellow, John made the most of his sojourn in Constantinople. At that time, the city was the centre of Greek learning par excellence. Even more strikingly, John’s visit took place just 17 years prior to the infamous destruction of the city by the Sultan Mehmed II’s Ottoman Turks in 1453.

Constantinople offered John an unparalleled opportunity to study the Greek language and to complete an etymological work about the Greek text of the Scripture. But perhaps most importantly, and entirely unbeknownst to him, his visit would prove one of the final times that valuable ancient manuscripts were able to leave the city. During his trip, John assembled a heterogeneous collection of Greek codices from the city’s vast markets, ancient libraries, and rich palaces. Somewhere in the city, John acquired the manuscript that came to be known as Palatinus Graecus 398, transporting it thereafter to Switzerland, presumably amongst his travel trunks.

Upon his return to Roman Catholic Europe, John bequeathed the entire collection to the Dominican convent in Basel. There our manuscript remained in the care of the monks until the 1550s when a printer, a certain Hieronymus Froben, obtained the manuscript. Froben had been commissioned to produce editions of its contents and, for reasons that I have not yet been able to discern, he never returned the manuscript to the convent. Instead, in 1553, Froben presented the folio to the Elector of the Palatinate, Ottheinrich, who had founded a library, known as the ‘Palatine Library’, in Heidelberg. There the codex was rehoused and listed under its present number, 398.

In 1623, after the capture of Heidelberg, the Palatine Library was offered to Pope Gregory XV by Maximilian I, Duke of Bavaria, as a gift in return for Pope’s financial assistance. The keeper of the Vatican Library, Leo Allatius, took possession of the collection and tore all the covers from the books. From there, Allatius carried them to Rome where they were rebound in the Vatican. Codex Palatinus Graecus 398 remained in the Vatican Library until 1797 when it was looted, alongside many other texts, and carried off to Paris on the orders of Napoleon.

In 1815, the King of Prussia Frederick William III of the House of Hohenzollern requested the restoration of the Palatinate Library to the University of Heidelberg. With the aid of Pope Pius VII, the return was coordinated and the codex Palatinus Graecus 398 was restored to Heidelberg in 1816, where we find it today.

Sources

Remarks on the marginal notes in codex Palatinus Graecus 398 (the stories of Parthenius and Antoninus Liberalis). University of Crete. Eva Astyrakaki (2017)

The Metamorphoses of Antoninus Liberalis. F. Celoria (1992)

The Tradition of the Minor Greek Geographers. American Philological Association. A. Diller (1952)

Appendix II: Hanno in the Ancient Sources

The oldest reference to Hanno outside that of the periplus is found in the work of the Greek historian Herodotus of Halicarnassus (ca.480-425 BCE), who states that:

The Carthaginians tell us that they trade with a race of men who live in a part of Libya beyond the Pillars of Herakles. On reaching this country, they unload their goods, arrange them tidily along the beach, and then, returning to their boats, raise a smoke. Seeing the smoke, the natives come down to the beach, place on the ground a certain quantity of gold in exchange for the goods, and go off again to a distance. The Carthaginians then come ashore and take a look at the gold; and if they think it presents a fair price for their wares, they collect it and go away; if, on the other hand, it seems too little, they go back aboard and wait, and the natives come and add to the gold until they are satisfied. There is perfect honesty on both sides; the Carthaginians never touch the gold until it equals in value what they have offered for sale, and the natives never touch the goods until the gold has been taken away

Herodotus, Histories, 4.196

It is very possible that Herodotus’ story is based upon Hanno's original report.

Later, the Greek author Arrian of Nicomedia (second century CE) writes of Hanno:

The Libyan Hanno left Carthage and sailed beyond the Pillars of Herakles on the Atlantic Ocean, keeping Libya on his left hand. He sailed eastwards for thirty five days. But when he turned to the south, he encountered many problems: lack of water, burning heat and rivers of fire flowing into the sea.

Arrian, Indike, 43.11-12

Finally, Hanno appears in the Roman encyclopaedia authored by Pliny the Elder. Pliny is not a credulous writer: he dismisses several stories which grew up around Hanno's journey as fabrications. This should encourage us to take the comments that Pliny does choose to share as relatively reliable:

Hanno, a general of the Carthaginians, penetrated as far as these regions, and brought back an account that the bodies of the women were covered with hair, but that the men, through their swiftness of foot, made their escape; in proof of which singularity in their skin, and as evidence of a fact so miraculous, he placed the skins of two of these females in the temple of Juno, which were to be seen there until the capture of Carthage.

When the power of Carthage flourished, Hanno sailed round from Cádiz to the extremity of Arabia, and published a memoir of his voyage, as did Himilco when he was despatched at the same date to explore the outer coasts of Europe.

Pliny, Natural History, 2.169, 5.8, 6.200

Syncretism. Compare, for instance, the arrival of the Magna Mater, Cybele, an Anatolian goddess, in Rome in 205 BCE.

David Richter; et al. (8 June 2017). "The age of the hominin fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, and the origins of the Middle Stone Age". Nature. pp. 293–296.

Werner, A. (January 1913). "The Languages of Africa". Journal of the Royal African Society. 12 (46): 120–135. JSTOR 715866.