Programming note: This is the first instalment in a series on London Sewage.

Dr John Snow: Mapping cholera

In 1854, English physician Dr John Snow was living on Sackville Street in London’s Piccadilly and working at the nearby Charing Cross Hospital.

Snow was a pioneer in the development and safe administration of anaesthetics. His success was such that, a year earlier in 1853, he had been selected to administer chloroform to Queen Victoria during the birth of her eighth child, Prince Leopold.

But as the late summer’s haze settled over London, Snow was consumed by an altogether different challenge which would, ultimately, transform epidemiological history.

Between 31st August and 1st September 1854, in Soho, a nearby part of town, Snow records how:

The most terrible outbreak of cholera which ever occurred in this kingdom… took place within 250 yards of the spot where Cambridge Street joins Broad Street, there were upwards of 500 fatal attacks of cholera in 10 days.

The mortality in this limited area probably equals any that was ever caused in this country, even by the plague.

Dr John Snow, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera (1855)

Cholera is a severe bacterial infection that typically presents with sudden onset of diarrhoea and vomiting, leading to rapid dehydration that can be fatal within hours if left untreated.

At the time, the predominant belief in the medical community was that cholera was transmitted by “miasmatic particles” that circulated in the air. Snow, by contrast, suspected that cholera infection was communicated through water systems with poor sanitary conditions via a faecal-oral route. He theorised this on the basis that symptoms appeared first in the stomach and bowel rather than the respiratory system.

Snow sought to test his hypothesis in relation to the new outbreak by examining nearby water sources. Quickly, he identified a water street-pump at the intersection of Broad Street and Cambridge Street as the most likely source of the outbreak:

As soon as I became acquainted with the situation and extent of this irruption of cholera, I suspected some contamination of the water of the much frequented street-pump in Broad Street, near the end of Cambridge Street; but on examining the water, on the evening of the 3rd September, I found so little impurity in it of an organic nature, that I hesitated to come to a conclusion.

Dr John Snow, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera (1855)

Although microscopic inspection did not yield further information, Snow was undeterred.

Changing tack, he paid a visit to the General Register Office to obtain a list of cholera deaths recorded that week in the Soho districts around Golden Square.

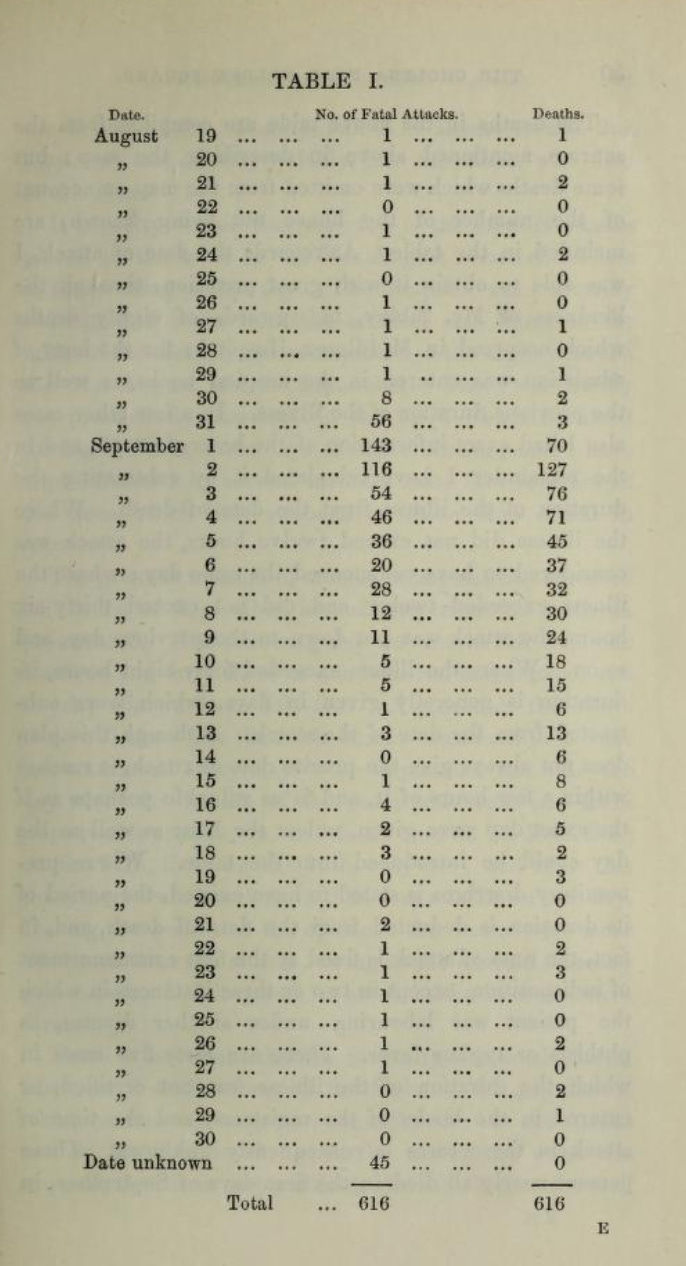

Snow identified the home addresses of 89 of the 616 fatal cases that he had tabulated. He then methodically interviewed relevant families and survivors to determine if the victims had consumed water from the pump. These interviews repeatedly confirmed that known victims of the outbreak had contracted cholera after drinking water from the pump, whether directly or through other means. Altogether, Snow documented that at least 69 of the fatalities had consumed water from the Broad Street pump.

Even apparent outliers, upon further investigation pointed back to the pump. For instance, there was a case of a 59-year-old woman who lived several miles away from the pump, in Hampstead. Upon interviewing her son, Snow discovered that the lady received a daily delivery of water from the Broad Street pump, as she preferred its taste. Snow wrote:

The water was taken on Thursday 31st August, and she drank of it in the evening, and also on Friday. She was seized with cholera on the evening of the latter day and died on Saturday.

Dr John Snow, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera (1855)

Another case study that further strengthened Snow’s evidence was the discovery that workers at a nearby brewery, who drank beer instead of water, and residents of a workhouse, who drank from their own water supply, remained largely unaffected

After compiling his evidence, Snow became convinced that the Broad Street pump was the true source of the outbreak and presented his findings to the local authorities investigating the matter — the Board of Guardians. The Guardians, although incredulous, nonetheless agreed to remove the handle from the pump.

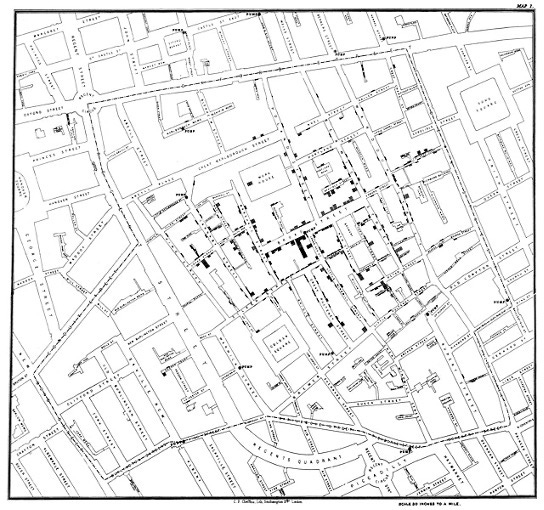

With a view to communicating his findings to a broader audience, Snow famously produced a cartographic illustration of the data that he gathered.

The decision to visualise the cases on a map to demonstrate the spatial distribution of cholera cases during that outbreak, with stacked black bars marking each death at the victim’s address, was a shrewd and novel communication strategy.

But despite this work, Snow’s theory faced broad rejection. The medical establishment remained sceptical, with The Lancet publishing editorials dismissing his conclusions. Similarly, the Medical Committee of the Board of Health, commissioned by the government to investigate the outbreak, rejected his theory outright.1 The Medical Committee’s President, Sir Benjamin Hall, stated that: “After careful inquiry we see no reason to adopt this belief.”

In producing his analysis, Snow had relied on statistics and data compiled by the General Register Office (GRO).2 Yet, key players at the GRO, such as the statistician William Farr, the Compiler of Abstracts, still adhered to the miasma theory. In his post, Farr delivered pioneering work in the field of vital statistics by systematically collecting and analysing mortality data and played a key role in compiling the data relating cholera outbreaks. During the 1848-49 epidemic, which killed over 53,000 people in England and Wales, Farr’s work was instrumental in mapping mortality patterns and he published a landmark report which provided the statistical evidence of cholera’s distribution across London and other regions. But, unlike Snow, Farr correlated cholera deaths with low elevation and proximity to the River Thames.

In his treatise, Snow also noted that some commentators had blamed the outbreak’s severity on recent sewer construction in the area, provoking a surge in the volume of miasmatic particles in circulation. The sewage project’s chief engineer, a certain “Mr Bazelgette” [sic.], was compelled to commission a report demonstrating that areas with repaired sewers had experienced notably lower mortality rates.

In the particular houses in this street where deaths have not taken place, it is satisfactory to be able to report that they are comparatively in an efficient state of drainage both into the new and old sewers, and without cesspools.

Edmund Cooper, Report to the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers on the house-drainage in St. James, Westminster during the recent cholera outbreak. 22 September 1854.

We shall return to Mr Bazalgette in a later instalment.

Reverend Henry Whitehead: Updating priors

How, then, did Snow’s theory come to be general consensus?

At the same time as the government-backed Medical Committee, the local Vestry of St James’ set up its own investigative committee.3

In Victorian London, the Vestry was a form of local government that played a significant role in administering parish affairs. The Vestry of St James, like other vestries in Victorian London, functioned as a form of local government that evolved from church administration to civic authority. Composed primarily of property-owning middle and upper-class residents, the St James Vestry oversaw a district of dramatic contrasts—from London's wealthiest streets to overcrowded tenements just a stone’s throw away.

In the case of this inquiry, the Vestry Committee comprised 16 members including Dr John Snow as well as a certain Reverend Henry Whitehead.

Reverend Henry Whitehead was a 29-year old clergyman serving his first curacy at the local church, St. Luke’s on Berwick Street. During the fiercest days of the 1854 cholera outbreak, the young curate worked incessantly to bring help and comfort to the afflicted and bereaved.

At the Vestry Committee, Snow and Whitehead met for the first time:

Snow had just completed his book On Cholera, which was published in January I855, and he presented a copy to Whitehead. But, having read it, the young curate remained unconvinced. He wrote to Snow setting out his reasons and stating that, in his opinion, an intensive inquiry would reveal the falsity of the argument attributing the spread of cholera to the Broad Street pump.

Sidney Chave (1958) Henry Whitehead and Cholera in Broad Street as well as Medical History 11(2), 92-109, 1958

Whitehead was also sceptical of Snow’s theory.

To his great credit, however, Whitehead did not dismiss the theory out of hand. Instead, Whitehead set about conducting his own inquiry with the aim either of confirming or refuting Snow’s hypothesis.

The ordinary course of my duties taking me almost daily into the street, I was under no necessity to be either hasty or intrusive, but asked my questions just when and where opportunity occurred, making a point of letting scarcely a day pass without acquiring some information and not caring how often I had to verify it in quarters where I could rely upon a willingness to converse upon the subject.

Reverend Henry Whitehead, Report on the Cholera Outbreak by the Cholera Inquiry Committee (1855)

In that way, Whitehead meticulously collected a set of “full statistical information [from] St Luke’s district.” In the course of his investigation, Whitehead personally contacted 497 of the 896 residents present during the outbreak. In summary, he found that:

Of 56 resident fatalities, only 2 had not consumed the pump water.

Of 28 non-resident fatalities, 24 worked in factories where the pump water was regularly used.

Of 50 residents who contracted cholera but survived, 35 had consumed pump water after 30 August.

Of unaffected residents, 279 had not drunk pump water between late August and early September, whilst 43 had.

From this data, Whitehead calculated that the mortality ratio for pump water drinkers was 80:57, compared to just 20:279 for non-drinkers.

In such a way, Whitehead prepared an analysis characterised by the rigorous objectivity of genuine scientific inquiry. What is more, in light of the statistical evidence, Whitehead began to conclude “slowly and, I may add, reluctantly… that the use of this water was connected with the commencement and continuance of the outburst”. Anecdotally, too, Whitehead’s investigation contributed examples:

From St. Luke's pulpit on September 8th, I congratulated the poor old women who formed a considerable proportion of the congregation upon their remarkable immunity from the pestilence.

The escape of these women, many of whom, living alone, had no-one to send to the well, was one of those “eccentricities” which found their best explanation in the pump theory.

Reverend Henry Whitehead, Report on the Cholera Outbreak by the Cholera Inquiry Committee (1855)

As a result, Whitehead determined to submit his findings in a report to the Vestry Committee.

Finally, Whitehead uncovered a pivotal piece of evidence:

One day last week, I happened to be studying the Registrar's Returns (of deaths) for a purpose unconnected with this matter, when my eye fell upon the following entry:

“At 40, Broad Street, 2nd September, a daughter, aged five months, exhaustion after an attack of Diarrhoea four days previous to death.”

Reverend Henry Whitehead, Report on the Cholera Outbreak by the Cholera Inquiry Committee (1855)

Why did this note capture Whitehead's attention?

It held dual significance: not only did the infant's case occur in the house nearest the Broad Street pump, but it also predated the major outbreak by roughly 48 hours.

About to submit his report to the Vestry Committee, Whitehead instead hurried to interview the deceased child’s mother. He found the bereaved woman living in a ground-floor back room at 40 Broad Street, having lost both her infant and her husband, a policeman, to cholera. To Whitehead’s questions, she provided a description of her actions during her child’s illness. She had soaked the soiled nappies in water buckets, then emptied this contaminated water into the cesspool at the front of the property.

Whitehead promptly obtained the Vestry Committee’s permission to examine the pump-well due to its alarming proximity to the cesspool. The subsequent inspection by surveyor Jehosephat York conclusively proved that faecal matter had leaked through the cesspool’s damaged brickwork into the well, just 3 feet away.4

In such a way, Snow and Whitehead each made thorough independent investigations of the outbreak. Whitehead’s work constituted a clear and independent confirmation of Snow’s hypothesis. As the Vestry Committee noted:

It was Dr. Snow who first endeavoured to trace out a relation [that] he supposed might exist between the use of this well-water and the cholera outbreak. The result of his laborious inquiry was in favour of that supposition.

Mr. Whitehead entertaining, at first, adverse views ended his special investigation of Broad Street by a remarkable confirmation of Dr. Snow's numerical results.

Report on the cholera outbreak in the Parish of St. James, Westminster, during the autumn of 1854. p.76 Source

As it happened, by the time that Snow has persuaded the Guardians to remove the pump handle, the cholera epidemic had already begun subsiding naturally. Fatal attacks had decreased from 142 on 1st September to just 14 by 8th September when the pump was closed

However, as Whitehead now observed, without the intervention of removing the handle, a second outbreak would almost certainly have occurred:

I must not omit to mention that if the removal of the pump-handle had nothing to do with checking the outbreak which had already run its course, it had probably everything to do with preventing a new outbreak, for the father of the infant, who slept in the same kitchen, was attacked with cholera on the very day (September 8th) on which the pump-handle was removed.

Whitehead concluded that:

There can be no doubt that [the husband’s] discharges found their way into the cesspool and thence to the well. But, thanks to Dr. Snow, the handle was then gone

Reverend Henry Whitehead, Remarks on the Cholera Outbreak in Broad Street, Golden Square, London, in 1854, Transactions of the Epidemiological Society of London, pp. 99-105 (1867)

It is worth reflecting on Whitehead's intellectual journey.

Whitehead, entered into Snow’s scientific controversy almost by chance and had no reason to doubt the truth of the prevailing doctrine. Indeed, at the outset, Snow’s indictment of the Broad Street pump seemed unsatisfactory to him just as it did to the medical inspectors of the Board of Health.

But, when the opportunity presented itself, Whitehead did not rest with theoretical objections. Rather, he sought out empirical evidence and his meticulous research ultimately confirmed the very hypothesis he had expected to disprove. Despite his lack of formal medical training, Whitehead conducted an investigation that demonstrated the essential qualities of scientific inquiry—unbiased measurement, rigorous data collection, and the ability to evaluate evidence objectively.

Moreover, Whitehead’s discovery of the specific mechanism by which the well became contaminated provided the final evidence that substantiated Snow’s theory. Without Whitehead’s statistical documentation and evidence of contamination, Snow’s explanation of the Soho epidemic would have remained an unproven conjecture.

Despite initial scepticism rooted in prevailing miasma theory and his own religious framework, Whitehead allowed the empirical evidence to transform his understanding of the problem.

John Netten Radcliffe: The East London cholera (1866)

After John Snow passed away prematurely in 1858, his hypothesis that cholera was water-borne and transmitted by polluted water remained unconventional and broadly disregarded by the mainstream.

Whitehead, meanwhile, continued at St. Luke's for two years post-epidemic before serving in various London parishes. Beyond his clerical duties, he took practical interest in social issues, particularly juvenile delinquency.

Then, in 1865, cholera once again threatened London, with several small cases foreboding a greater outbreak. In July 1866, a full-blown cholera epidemic did indeed break out in the crowded slums of East London. The Bishop of London sought volunteers with cholera experience and Whitehead responded immediately.

In East London, as the crisis unfolded, Whitehead came into contact with a man called John Netten Radcliffe, an epidemiological expert who had been dispatched as a medical inspector by the Privy Council’s Medical Department.5

Netten Radcliffe began conducting meticulous fieldwork informed by Whitehead’s prior experience and working with Whitehead’s support, both figuratively and literally (Netten Radcliffe was limping while recovering from the effects of a rheumatic fever, so would take Whitehead’s arm as support during fieldwork). Through their work in the community, the pair traced the cholera cases to the East London Waterworks Company’s supply, identifying the Old Ford Reservoir as the point of contamination.

A further investigation revealed that the company had failed to properly filter water from the River Lea, which had been polluted with sewage following heavy rainfall and flooding. The contaminated water had then been supplied untreated by the East London Waterworks Company into thousands of homes in the localities around the docks.

Thus, Radcliffe’s report to the Privy Council, published in 1867 as part of the Report on the Cholera Outbreak in the East End of London, provided conclusive evidence linking the unfiltered water to the outbreak.

Radcliffe also acknowledged Snow and Whitehead’s roles in his reporting:

This doctrine now fully accepted in medicine, was originally advanced by the late Dr. Snow; but to Mr. Whitehead unquestionably belongs the honour of having first shown with anything approaching conclusiveness the high degree of probability attaching to it. Only now perhaps can the great public importance of the doctrine be clearly appreciated, and the value of Mr. Whitehead's inquiry properly estimated

Privy Council, Ninth Report of the Medical Officer, for 1866. Appendix No. 7. Report by Mr. J. Netten Radcliffe on Cholera in London and especially the Eastern Districts, 1867 p. 288

At the same time, William Farr at the GRO was once again working on the cholera outbreak, meticulously analysing mortality statistics and distribution patterns to deliver a comprehensive statistical report on the cholera epidemic.

As early as 1856, after reviewing the evidence, Farr had begun to doubt his miasmatic conjecture, as reflected in his writings, although he did not make public this intellectual shift. In 1868, however, when Farr published his statistical analysis, he reported that the outbreak did not appear to correlate with elevation, but rather with areas supplied by a particular water company; the East London Waterworks Company.

Finally, Snow’s theory was firmly validated with the further evidence of this second water-borne epidemic, both by Netten Radcliffe’s fieldwork and by Farr’s statistical approach, which explicitly linked the outbreak to contaminated water.

The Poetry and Prose of Public Health

The methodological contrast between William Farr’s statistical approach and Reverend Henry Whiteheads community-based investigation illuminates complementary approaches to public health which remain relevant today.

Farr, from his position at the General Register Office, pioneered epidemiological statistics, viewing populations increasingly as biological “human units” whose differences could be measured and quantified in aggregate—establishing the scientific “prose” of public health.

Whitehead, by contrast, approached the same crisis through immersion in community life, knowing his parishioners as individuals with stories rather than merely as statistical subjects. His thorough investigation coexisted with genuine pastoral care; he conducted meticulous research whilst maintaining the “poetry” of human connection.

Although Snow successfully conjectured the source of cholera, it ultimately required both Farr’s rigorous data and Whitehead’s human insight to prove definitively that Snow’s water-borne theory was correct.

This episode is perhaps instructive for us today, not least given the absence of such collaborative success in relation to identifying the source of the most notable recent pandemic.

Bibliography

Contemporary Victorian source material:

William Farr (1852), Report on the mortality of cholera in England, 1848-49. Source

John Snow (1855) On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, (2nd edition, London: John Churchill). Source

Reverend Henry Whitehead (1855), Report on the cholera outbreak in the Parish of St. James, Westminster, during the autumn of 1854 / presented to the vestry by the Cholera Inquiry Committee. Source

Reverend Henry Whitehead, 'Remarks on the Cholera Outbreak in Broad Street, Golden Square, London, in 1854', Trans. Epid. Soc. of London, m, 99-105 (1867)

John Netten Radcliffe (1877), On the Diffusion of Cholera in Europe during the ten years 1865–74. Source

Secondary academic analyses:

Chave, Sidney (1958) “Henry Whitehead and Cholera in Broad Street as well as Medical History.” 11(2), 92-109. Source

Hilts, Victor L. (1970) “William Farr (1807-1883) and the ‘Human Unit.’” Victorian Studies 14, no. 2: 143–50. Source

Eyler, J. M. (1973) “William Farr on the cholera: the sanitarian's disease theory and the statistician's method.” J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1973 Apr;28(2):79-100. Source

Halliday, S. (2001) “Death and miasma in Victorian London: an obstinate belief.” BMJ. Dec 22-29;323(7327):1469-71. Source

P. Bingham, N.Q. Verlander, M.J. Cheal (2004) “John Snow, William Farr and the 1849 outbreak of cholera that affected London: a reworking of the data highlights the importance of the water supply.”Public Health, Volume 118, Issue 6, 2004, Pages 387-394. Source

Koch, Tom & Denike, Kenneth. (2009). Crediting his critics' concerns: Remaking John Snow's map of Broad Street cholera, 1854. Social science & medicine (1982). 69. 1246-51. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.046.

Appendix: Vestry Report table of individuals killed in 1855 cholera outbreak by occupation and gender

Medical Committee of the Board of Health. In Victorian England, the Board of Health was a central government body established through the Public Health Act of 1848, largely in response to increasing concerns about sanitation and disease in rapidly growing urban areas. It was created following Edwin Chadwick's influential 1842 report on the sanitary conditions of the working classes, which highlighted the connection between poor sanitation and disease outbreaks. The Board had the power to establish local boards of health in areas with high mortality rates and could require towns to implement sanitation improvements, including proper sewerage systems, clean water supplies, and waste removal.

The Medical Committee was a specialised division formed specifically to address cholera epidemics, which devastated Britain several times during the Victorian era (most notably in 1831-32, 1848-49, 1853-54, and 1866). This committee was tasked with investigating cholera outbreaks, tracking the disease's spread, and recommending preventative measures. It played a crucial role during the particularly severe 1848-49 epidemic, when the General Board of Health established a central authority to coordinate responses across the country. The committee gathered epidemiological data, issued guidelines on prevention and treatment, and worked to implement emergency measures in affected areas.

The General Register Office. In Victorian England, the General Register Office (GRO) was a central government institution established by the Births and Deaths Registration Act of 1836. It created England and Wales’ first systematic national framework for recording births, deaths and marriages, with the country divided into registration districts managed by superintendent registrars. Under the leadership of the Registrar General and with William Farr serving as its influential first statistical superintendent, the GRO transformed vital statistics into a powerful tool for public health reform. Its meticulous collection of mortality data proved particularly valuable during cholera epidemics, enabling officials to track disease patterns and identify problematic areas, ultimately contributing significantly to Victorian sanitation improvements and epidemiological understanding.

Committee of the Vestry of St James. In Victorian London, the Vestry was a form of local government that played a significant role in administering parish affairs. The Vestry of St James, like other vestries in Victorian London, functioned as a form of local government that evolved from church administration to civic authority. Composed primarily of property-owning middle and upper-class residents, the St James Vestry oversaw a district of dramatic contrasts—from London's wealthiest streets to overcrowded tenements just streets away. As the administrative body for both the affluent St James's parish in Westminster and the impoverished district of Soho, it wielded considerable influence over local affairs, managing everything from poor relief and public health to street maintenance and tax collection. It continued to exercise substantial local control until 1899, when the London Government Act abolished the vestry system in favour of metropolitan boroughs, marking the end of this distinctive form of Victorian local governance.

Report on the cholera outbreak in the Parish of St. James, Westminster, during the autumn of 1854 / presented to the vestry by the Cholera Inquiry Committee. Source, Mr. York's Report, pp. 170-4

The Privy Council is an ancient advisory body to the British sovereign that evolved from a powerful executive council into a largely ceremonial institution by the Victorian era, though it retained administrative functions particularly in emergency public health matters through Orders in Council.

The Medical Department of the Privy Council, established in 1858 under Sir John Simon, was an early centralised public health agency that investigated disease outbreaks, collected statistics, and produced influential reports on sanitation, playing a crucial role during the 1866 cholera epidemic through its field investigations and scientific recommendations. The Medical Department of the Privy Council no longer exists in its original form, as it was absorbed into the newly formed Local Government Board in 1871, marking an important transition in how public health was administered in Britain.

![Yours truly Henry Whitehead [signature] - NYPL Digital Collections Yours truly Henry Whitehead [signature] - NYPL Digital Collections](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6YrK!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9cf1b1b1-7516-47bc-9a61-f39227aed5d1_523x760.jpeg)