This is one to read when you are in the mood for some tougher conceptual thinking. This week I would like to reflect on the mechanics of money. I want to explore the following questions:

What is money?

How is money created and destroyed?

How much money there is?

Besides being a worthwhile topic in and of itself, I am interested in exploring the nature of money creation because it lays the groundwork for a discussion of quantitative easing, which will the subject of my next post. By examining the processes of money creation and destruction, we will be better prepared to grasp the mechanics of quantitative easing and its effects.

Let’s begin!

The origins of money

Money, money, money, must be funny, in a pre-historical world…

As I reflected on in an earlier piece, money may have arisen alongside or prior to debt at some time in pre-history.

It is entertaining to imagine the ways in which humans may have first experimented with systems of money. But, as with anything that happened in human pre-history (history prior to the invention of writing), we cannot know for certain how money really came into existence.

To tell the story of how money first arose, we have to rely on conjecture or logical inferences from an examination of the material cultures. That said, there is one particular study that I have come across that offers a unique perspective for theorising the origins of monetary systems.

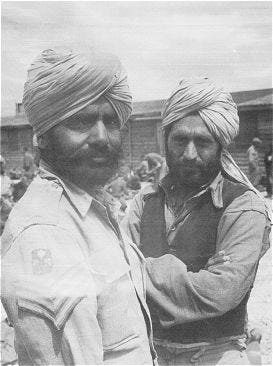

‘The Economic Organisation of a P.O.W. Camp’ was written in summer 1945 by Richard Radford, a British infantry officer who had been captured during the North Africa Campaign in Libya in 1942. Radford spent the remainder of the Second World War as a prisoner at a Nazi German prisoner-of-war camp in southern Bavaria known as Stalag-VII A.

Radford’s account of the camp is a remarkable piece of writing and well worth a full read. In the piece, Radford describes how market structures, trading, and money spontaneously appeared in the prisoner-of-war camp.

[Stalag VII-A] consisted of between 1,200 and 2,500 people, housed in a number of separate but intercommunicating bungalows, one company of 200 or so to a building.

Between individuals there was active trading in all consumer goods and in some services.

Most trading was for food against cigarettes or other foodstuffs, but cigarettes rose from the status of a normal commodity to that of currency.

Our supplies consisted of rations provided by the detaining power and the contents of Red Cross food parcels - tinned milk, jam, butter, biscuits, bully, chocolate, sugar, etc., and cigarettes. So far the supplies to each person were equal and regular. All these articles were the subject of trade and exchange.

Richard Radford, p.2

Resources within the confines of the POW camp were very limited, consisting almost exclusively of rations and Red Cross parcels. As a result, Radford recounts, cigarettes became the camp’s prevailing currency. Brilliantly, Radford goes on to describe how idiosyncratic market structures and, in particular, arbitrage opportunities arose based on individual’s different needs, abilities, and preferences:

Trading [of rations] quickly developed, because while prisoners had equal means they did not have identical preferences – the Sikhs sold their beef rations, the French were desperate for coffee. So middlemen who could speak Urdu or bribe a guard to let them visit the French quarters had the chance to make “small fortunes” in biscuits or cigarettes.

Richard Radford, p.2

After the liberation of the POW camp, Radford returned to Cambridge to complete his undergraduate economics which he had suspended to enlist at the outbreak of war. He later emigrated to Washington D.C. where he worked at the International Monetary Fund and taught at Johns Hopkins University.

Uses of money

What purposes does money serve in society? In short, money has three fundamental and complementary roles.

First, as we have already established, the holders of money believe that they will be able to exchange it for goods and services in the future. Formally, this use is known as being a medium of exchange. Anything can be used as a unit of exchange. In our society in daily life, that typically means coins, banknotes, or electronic cash, but in other human communities, like a prison, that might mean cigarettes.

Second, money can be used as a store of value. In others words, it can be saved up and, excepting inflation or deflation, can retain purchasing power into the future.

Third, money serves as a unit of account. In this use, money offers a standardised metric that provides an objective, measurable value for different goods and services. makes it easy to complete economic transactions, such as buying and selling

Returning for a moment to Radford, he illustrates this point with the cigarette currency:

Although cigarettes as currency exhibited certain peculiarities, they performed all the functions of a metallic currency as a unit of account, as a measure of value and as a store of value, and shared most of its characteristics. They were homogeneous, reasonably durable, and of convenient size for the smallest or, in packets, for the largest transactions.

A brief history of trust in money

Money relies on trust. Through history, money has often been a fragile social construct. Whether it is supplied through private means, in a competitive manner, or by a sovereign, money has always only been as good as the assets that back it.

As recently as this year, we have seen how a loss of trust and confidence can, under certain extreme scenarios, cause financial institutions to vanish overnight. Credit Suisse, First Republic Bank, Silicon Valley Bank, and Signature Bank are only the latest additions to a long list of other financial institutions through history that failed when trust in them dissipated and depositors fled.

The same holds true for trust in money. Even government-backed arrangements, where assuring trust in the instrument is a centralised task, regularly fail. Most famously, there was hyperinflation in Weimar Germany in the 1930s. More recently, Venezuela and Zimbabwe.

Through time, many different iterations of structures for trust have been tried in the world of finance. In the modern period, an early step was the establishment of chartered public banks in European city-states during the period 1400-1600 CE. These emerged to improve trading by providing a high-quality, efficient means of payment and centralising a number of clearing and settlement operations. Such banks, set up in trading hubs such as Amsterdam, Barcelona, Genoa, Hamburg and Venice, were instrumental in stimulating international trade and economic activity more generally. Through the centuries, however, all those original merchant banking houses have invariably collapsed or disappeared quietly.

So far, the best result from many millenia spent searching for a solid institutional underpinning for trust in money is central banks.

In the United Kingdom, for instance, the central bank is the Bank of England which guarantees sterling, which is the standardised money (or ‘currency’) in use and circulation in the UK. The Bank of England oversees the currency and manages the physical issuance of sterling.1 If ever the Bank of England is no longer considered a trusted guarantor of the currency, then we might expect the sterling currency to disappear too.

Sterling’s main unit is, of course, the pound, known also as the British pound or a quid. As far as I can tell, sterling takes two physical forms (coins and banknotes) and two digital forms (central bank reserves and commercial bank deposits).

Physical money

For most of recorded human history, the term ‘money’ has denoted physical objects.2 Originally, these physical objects encompassed a wide range of commodities from the productive - livestock to grain - to the merely attractive - shells, precious stones and metals, objects that were exchanged either through barter or bilateral IOUs.

Still today, we live in a world with physical money - both coins (also referred to as ‘commodity money’) and banknotes (also known as ‘representative money’) are in common usage globally as forms of currency.

Coins first became widespread in China, India, and Lydia in Asia Minor at very similar times in the archaeological record between 600-500 BCE.3 The first known banknote is from 7th-century China, used by merchants as a receipt of deposit during the Tang dynasty.4

In and of themselves, coins and banknotes as physical objects are of minimal use. In the context of our human societies, however, they can take those uses outlined above - as a unit of account, as a measure of value and as a store of value. This means that the monetary value of a coin or banknote can be far in excess of the value of the material itself since holders believe that they will be able to exchange this money for goods and services in the future.

Digital money

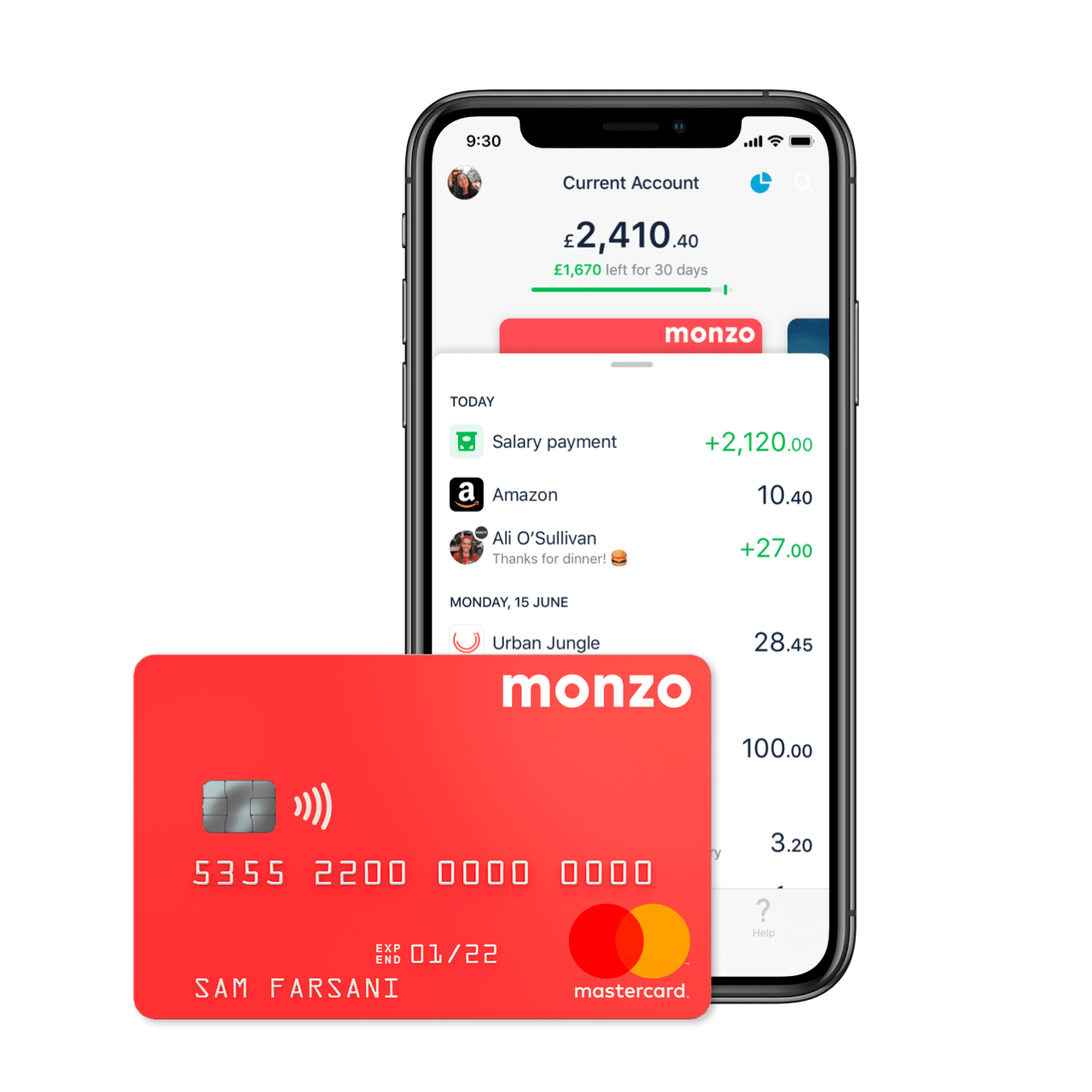

Since the dawn of the digital age, ‘money’ has also referred to digital money in the form of bank deposits (termed ‘commercial bank money’) or the reserves held by commercial banks at the central bank (‘central bank reserve money’).

When I talk about commercial bank money or bank deposits, I am referring to any bank account held by an entity at a financial institution. That entity could be an individual like you or me with a digital current account at a ‘high-street’ bank, or a business, like your local newsagent or a major listed company with a business deposit account at a bank.

To my knowledge, the first public interface with digital money was an automated teller machine (ATM) that was installed by Barclays Bank in its Enfield Town branch in North London on 27 June 1967.

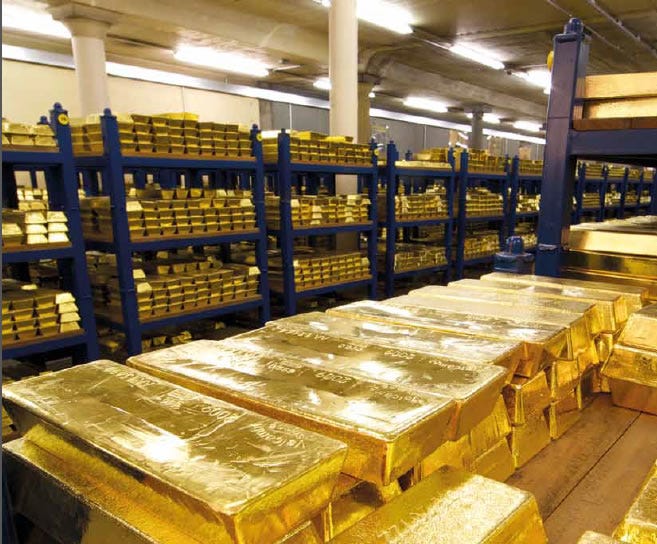

When I refer to central bank reserves, you might reasonably assume that I mean gold bars stored by commercial banks (like Lloyd’s or HSBC) at a central bank (the Bank of England). And indeed, at least in the past (when central banks used a ‘gold standard’) this was what was meant by ‘reserves’. As it happens, even today there are about 300 tonnes worth of gold bars still sitting in the Bank of England’s vaults beneath the City of London, despite the fact that the gold standard was abandoned in 1931 (these bars are the survivors of the events of 1999 when Gordon Brown sold off about 400 tonnes of UK gold at a price that transpired to be a 50-year low).

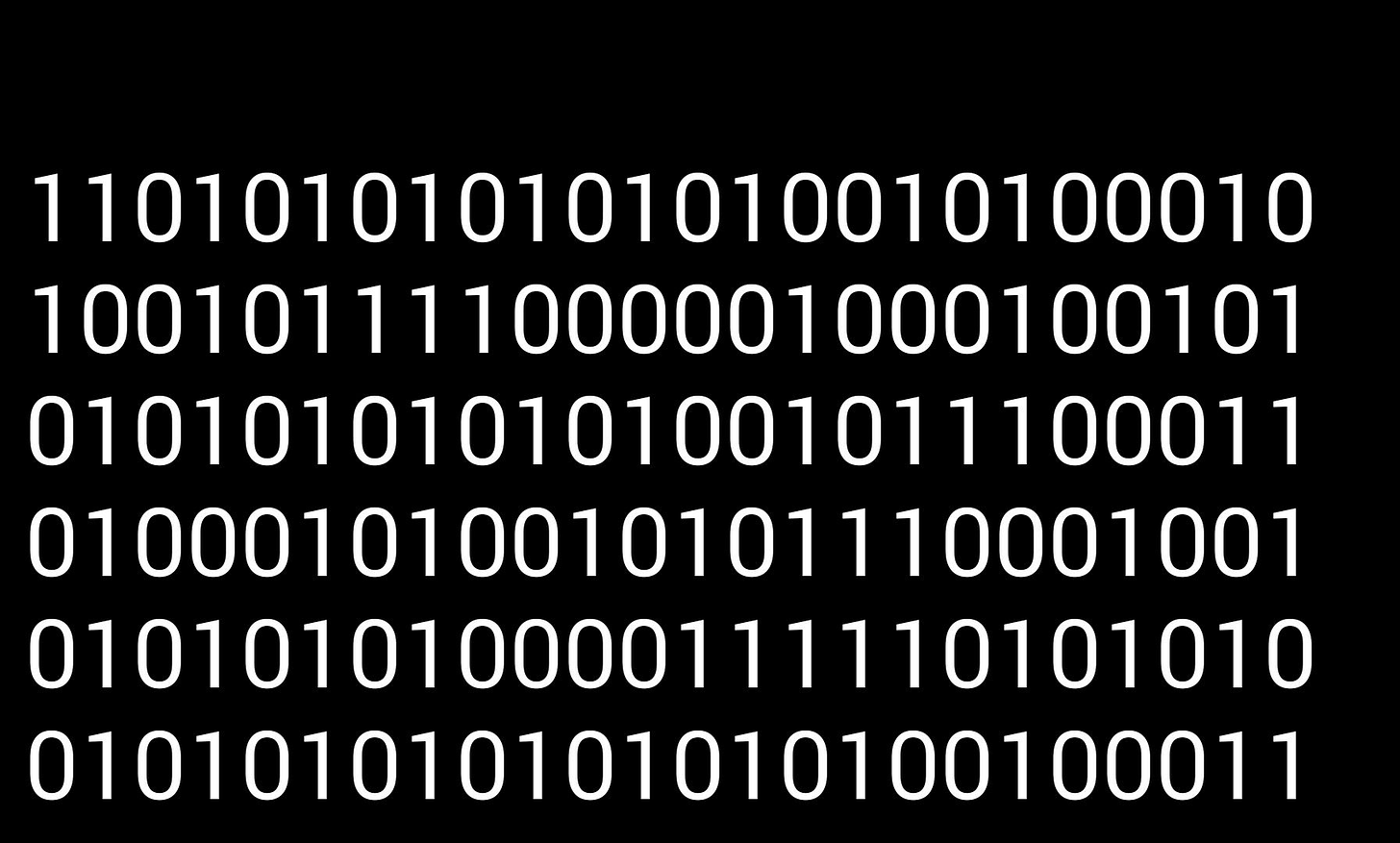

Today, almost all central bank reserves are a form of electronic money. They are electronic numbers, ultimately binary code, ones and zeroes, recorded in digital bank accounts. This is what I mean when I talk about reserves, electronic money again.

These particular reserve bank accounts held at the central bank are different to a bank account that you or I might use. The difference is that only a select type of qualified entity can hold them. Qualifying entities are financial institutions, typically large banks.

In the UK, just 3% of all money is made up of the physical stuff - coins and banknotes.

The vast majority of money, the remaining 97% in the UK, is held electronically as digital money. Of this, 18% is held by commercial banks as digital reserves at the central bank, while the remaining 79% consists of bank deposits held by private individuals and entities at commercial banks.

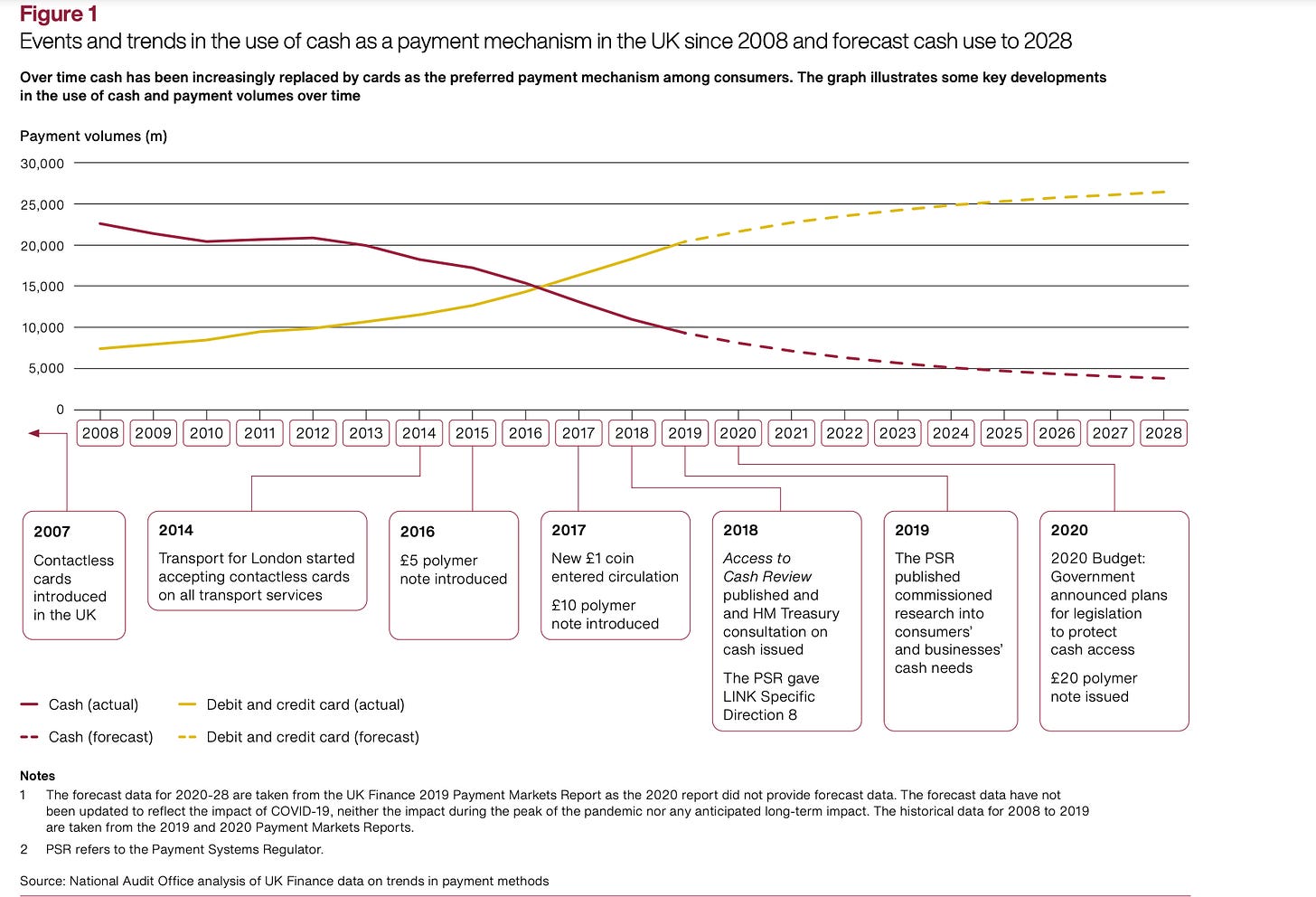

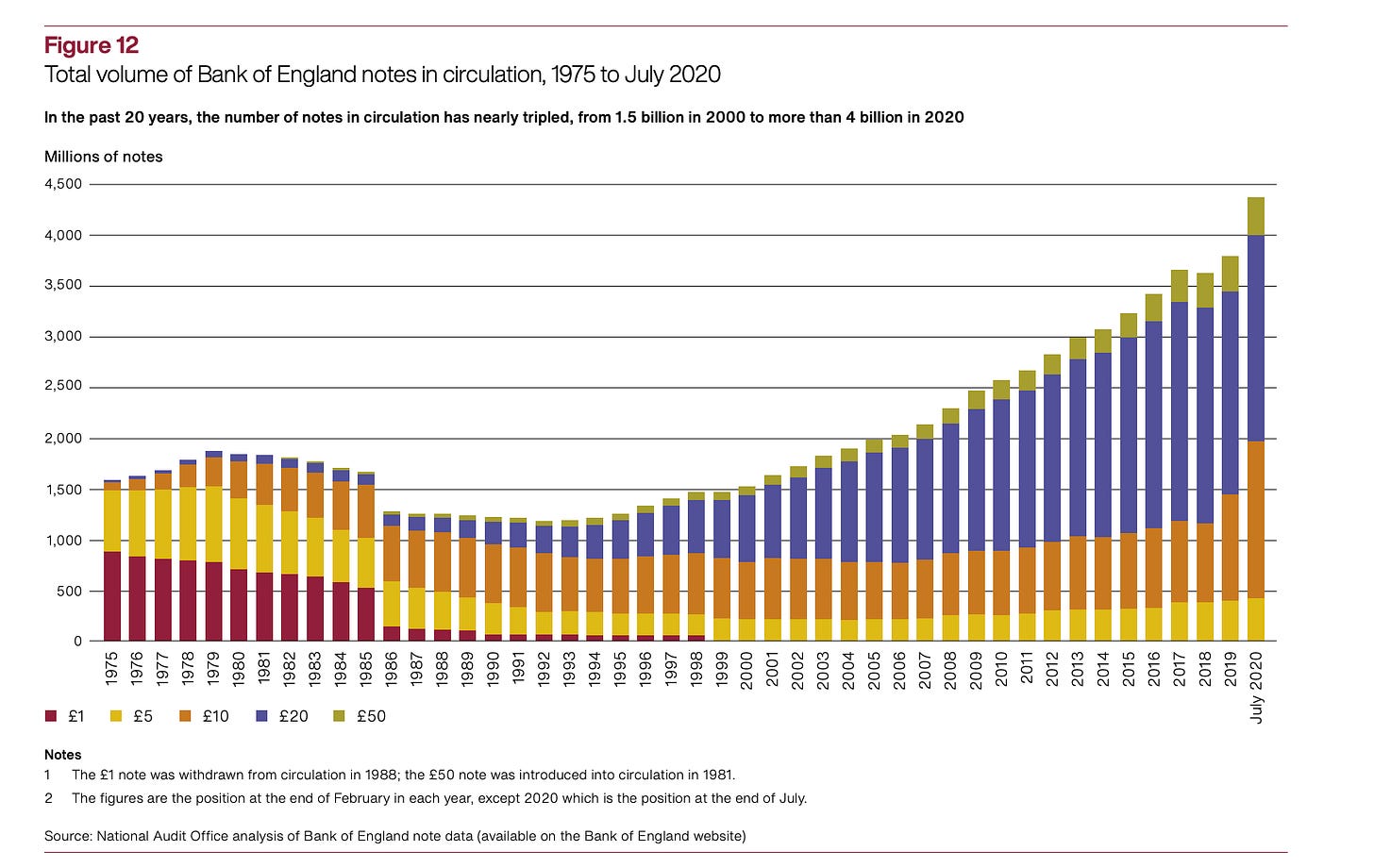

As the chart below from the National Audit Office demonstrates, electronic payments have increasingly become the primary source of money for a majority of individuals.

As an aside, these days when you say ‘digital currency’ or ‘electronic money’, most people’s minds leap to cryptocurrencies. This is emphatically not what I am talking about.

In particular, the feverish excitement around central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) seems odd to me. We already have a digital currency issued by a central bank? Namely, the electronic money that is being used literally 97% of us all of the time. The main merit of crypto is supposedly that it is decentralised - if its being issued by a central bank, that is about as central as it gets.

I expect to hear from crypto-evangelists. With some merit, they may explain how digitisation is not the point, rather it is the operational method of recording ownership by using a token-based distributed ledger system rather than account-based that matters. And I look forward to telling them that I simply do not care.

Perhaps that is unfair - might a blockchain somehow make it easier to keep track of who owns what? Again, I refer them to the fact that I do not care. I have never really understood why keeping track of asset ownership on a blockchain was better than keeping track of it in a centralised database run by a trusted intermediary, but people have sure talked about it a lot. Personally, I have already expended far too much of my life on this periphery, operational topic to care about it anymore.

Money creation

How is physical money created?

The creation of physical money, being a tangible process, is relatively easy to visualise.

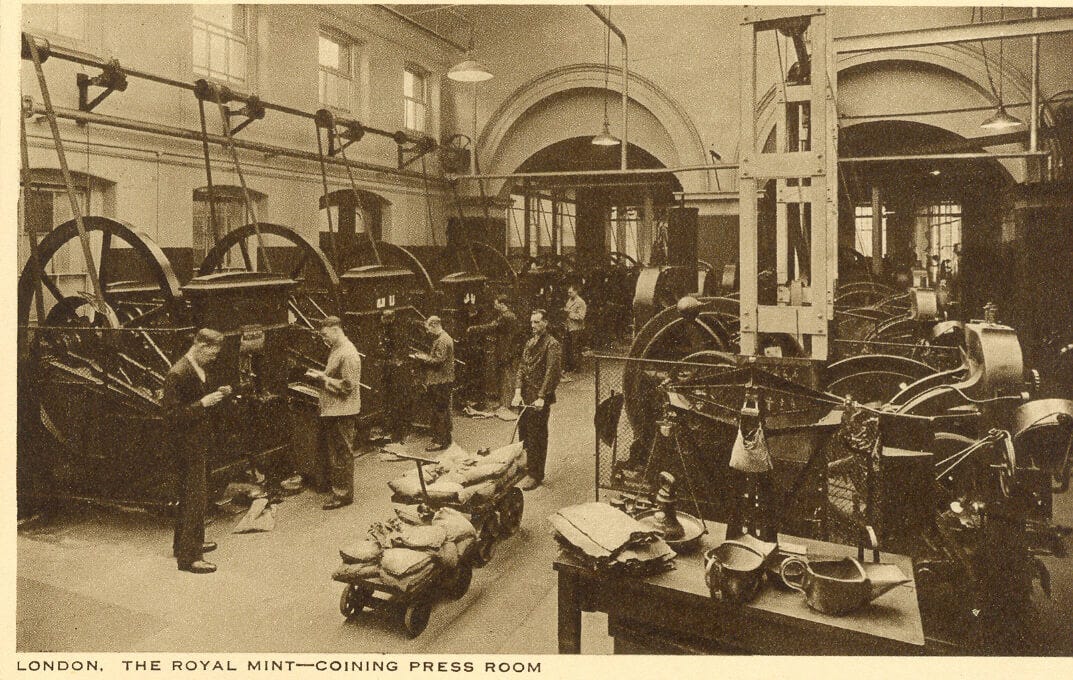

Coins and banknotes are literally minted and printed. In the United Kingdom, this is done by The Royal Mint, currently based in Llantrisant in Glamorgan, Wales (formerly of Tower Hill, City of London).

Here are archival images of money creation by the Royal Mint in the early 20th century, from silver melting, to coin pressing, to weighing:

The creation of digital money is less intuitive to imagine.5

The creation of digital central bank reserves is the more straightforward of the two. It happens when a central banker inputs numbers into the accounts of commercial banks at the central reserve. Literally, digital numbers typed or coded to change the number that appears in the bank account of the commercial bank at the central reserve.

So that covers coins, banknotes, and central reserve digital money. But that still only accounts for about 21% of the total money supply in the UK economy.

What about the other 79% of electronic money that is in circulation in the economy? The bank deposits and commercial bank money.

How is digital money created?

The best way perhaps to understand how electronic bank money is created is to think about how banking works.

Fractional reserve banking

In my experience, the way banking is taught in economics textbooks is as follows (this theory of banking is called fractional reserve banking):

Banks receive deposits from savers (say £100 of deposits), they keep a percentage of those deposits on hand as cash (say 10%, £10 of cash reserves) and then lend out the remaining deposits as loans to borrowers (say £90 of loans). In this description, the loans given out by the banks to borrowers are effectively the same money given to the bank by savers. The fraction of the savers’ money kept as reserves on hold at the bank is ready for when any of the savers requests the money from an ATM or uses their debit card.

Similarly, in this model of banking, a bank that simply took in deposits and kept them all safely there, lending out none of them would be a full reserve bank.

Unfortunately, fractional reserve banking is an imaginary, or at least a very inaccurate, way of describing how modern banking actually works, although it is adjacent to the truth.

The reserve requirement for banks was eliminated altogether in 2020 (though liquidity regulation has some related effects). Likewise, at least to my knowledge, no full reserve bank exists (feel free to correct me on this one).

Credit creation (actual banking)

So how does banking actually work? In reality, banks do not lend out the money deposited with them. Rather, they take deposits and then create new money out of thin air to lend out.6

Here is a description of what actually happens when a bank grants a borrower a loan is (let’s call this theory actual banking or credit creation):

Banks receive deposits from savers (say £100 of deposits). This is good for the running of the bank’s business, but largely irrelevant to the business of lending. The bank may use this cash however it sees fit (within reason as determined by banking regulatory rules). The bank loans money to borrowers (say £1000 of loans), the money that it loans is created the moment that the loan is agreed and the numbers are typed into the borrower’s account. Savers, meanwhile, can access the money deposited whenever they desire through an ATM, or debit card transaction, unless, for some reason, they all demand their money back simultaneously, in which case it will not be there (usually, it is being used to shore up the bank balance sheet, perhaps in the form of short-term money market instruments, or perhaps in long duration bonds, or in the form of funding for lending activities). This unfortunate scenario is also known as a ‘bank run’. If these pesky depositors really are insistent on having their money back, the bank will not be able to meet these demands and collapse into bankruptcy. See the aforementioned Credit Suisse, Silicon Valley Bank et al.

To put this another way, electronic money is effectively created when a banker is willing to extend credit to a borrower. When a commercial bank (or other deposit-taking financial institution) approves a businesswoman for $1 million loan, the commercial bank electronically creates those deposits through a few keystrokes out of thin air. The newly created $1 million deposit liability appears on the bank’s balance sheet and a newly created $1 million loan asset appears on the other side of the balance sheet, balancing it.

In short, electronic money in circulation in the economy is the product of credit creation.

Who creates money?

Bank lending appetites & credit crunches

At a micro-level, credit creation is determined by, for example a high-street banker who loans out money to entities, whether that be mortgages for residential properties, or credit allowances for credit cards, or business loans for capital expenditures.

At a broader level, the extent of money creation in the wider economy is determined by banks’ executive committees and management teams who decide what a given bank’s top-down risk appetite for lending will be.

Ultimately, the amount of money sloshing around our modern economy is determined by the lending appetite of commercial banks. When a recession hits or a bank fails (often related), banks in general tighten their lending standards. This reduces the amount of money being created for that period of time. This tightening of lending standards is also known as a ‘credit crunch’.

The condition of lending conditions can be estimated by proxy indices that compile different loan officer, lending standard and other sentiment indicators to establish the prevailing lending conditions (like the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices or SLOOS).

Central bank interest rates

This bank lending appetite is heavily influenced by the central bank’s interest rate.

The prevailing lending rate (‘interest rate’) at the central bank is set by a committee of senior central bankers at regular meetings and is pretty much the only tool available to them for steering the economy. Central bankers use the interest rate first and foremost to try to maintain the rate of price changes (inflation) or rate of unemployment.

The rate that the committee of central bankers agree to set at each meeting is the rate of interest that the central bank will pay on money held in accounts at the central bank reserve by qualified institutions (banks etc). In the UK, the rate is agreed by the Bank of England’s (BOE) Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) and known as the Prime Base Rate. In Europe, it is set by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) Governing Council (GC) and is known as the Main Refinancing Rate. In the United States, it is established by the Federal Reserve System’s (Fed) Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and is known as the Federal Funds Effective Overnight Rate.

When the rate set by the central bank moves higher, then commercial banks will in turn raise their depositors’ interest rates (the amount they pay their depositors) as well as their lending interest rate (the amount their debtors pay them for loans, credit cards, mortgages etc.). As the rates go higher, banks typically become more cautious about who they are willing to lend money, since higher rates are much more difficult for borrowers to meet and lead to more delinquencies, defaults, and bankruptcies.

Quantitative easing

To wrap up money creation, we have covered (i) creating physical coins and banknotes and (ii) creating digital electronic money through credit creation or central bank reserves.

Besides these, there is one other way to create money of which I am aware which is closely related to creating central bank reserves; namely, quantitative easing. I will return to QE in a future instalment and describe its mechanics in detail there. In brief, a central bank does a type of money creation when it purchases assets through QE.

Money destruction

How is money destroyed?

Money can be destroyed in a number of ways.

With physical money, it is again easier to imagine. It can be lost (apparently, in 2007, £65m had been lost in 1p coins alone). It can be taken out of circulation by the central bank. Or, money can be intentionally destroyed. See, for example, the stunt below when the British band K Foundation burnt one million quid in August 1994 in the back of a disused boathouse on the Ardfin Estate on the Scottish island of Jura.

As an aside, the European Central Bank ceased production of 500 notes in 2019 in an effort to combat illicit activities, since the banknote could facilitate large cash payments. At the same time, a new series of €100 and €200 bills will be introduced on May 28, 2019.

Paying off debt

Most importantly, the inverse of credit creation can also happen - credit destruction, otherwise known as paying off your debt.

The way to think about this is that each time a borrower pays back the principal on a loan, whether in instalments or all at once, money is destroyed. The bank collects the interest along the way, but when the actual debt is paid back, the liability on their balance sheet reduces and so does the asset.

Inflation

This one is not money destruction per se, but rather the destruction of the value of money, it’s purchasing power.

Inflation is an extraordinary phenomenon that is difficult to really pin down. In academic terms, the rate of inflation describes the increase in prices over time - it measures how quickly prices of goods and services are rising.

For the first time in decades, we are experiencing a period of high inflation again. In the UK, in particular, just yesterday we saw another monthly recording of inflation at 8.7% year-on-year. Inflation becomes more dangerous the longer is lasts, as it is all about expectations. The more people get used to price rises, the more price rises they anticipate in the future, potentially creating a vicious spiral towards hyperinflation.

Radford is helpful here again in illustrating inflation using the setting of the POW camp:

Our economy was repeatedly subject to deflation and to periods of currency inflation and deflation.

While the Red Cross issue of 50 or 25 cigarettes per man per week came in regularly and while there were fair stocks held, the cigarette currency suited its purpose admirably. But when the issue was interrupted, stocks soon ran out, prices fell, trading declined in volume and became increasingly a matter of barter.

This deflationary tendency was periodically offset by the sudden injection of new currency. Private cigarette parcels arrived in a trickle throughout the year, but the big numbers came in quarterly when the Red Cross received its allocation of transport. Several hundred thousand cigarettes might arrive in the space of a fortnight. Prices soared, and then began to fall, slowly at first but with increasing rapidity as stocks ran out, until the next big delivery.

Most of our economic troubles could be attributed to this fundamental instability.

This discussion of inflation and deflation in the cigarette currency economy of the prisoner-of-war camp is worth bearing in mind when we cover quantitative easing next time.

If I have forgotten any other ways in which money can be created or destroyed, please do get in touch. I look forward to being told about any particularly arcane methods that I have missed.

Measures of money supply

How much money there is?

A short final series of thoughts on this question.

Quite frankly, you have done superbly well if you have waded through my incoherent prose and made it this far. For that reason, to reward yourselves, I would suggest that you may prefer to watch the video below rather than reading my words for this final question.

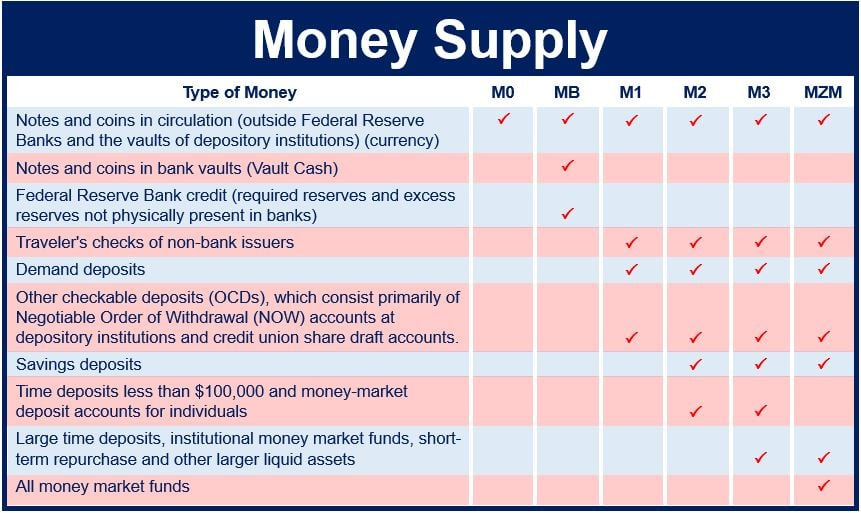

If you prefer words then, in short, there are well-established quantitative methods for measuring the money supply. Money supply data is recorded and published at national levels, usually by a government agency or the central bank of the country in question.

A popular way of categorising money is as follows, in order of liquidity and fungibility:

Here for instance, are the ECB’ estimates for money supply in the Euro Area

And here is the Federal Reserve’s estimates of US M4 money supply:

One more:

Naturally, how much money there is simply depends on what forms of money you decide to include in your definition. Typically, the answer is that there is rather a lot of it out there.

That’s all for today, I hope that was interesting and or insightful. More soon on quantitative easing.

Bibliography

For Richard Radford:

The Economic Organisation of a P.O.W. Camp, November 1945

Rules of trading in a POW camp, Tim Harford, May 2012

Matt Levine, both for his content and his style:

Silicon Valley Bank Ran Out of Money, 23 March 2023

Banking Gets a Bit Narrower, 20 April 2023

It’s Never Too Late for Banks to Hedge, 9 May 2023

Joe Weisenthal:

Ban all the Banks: Here's The Wild Idea That People Are Starting To Take Seriously, 27 April 2014

Bank of England:

Money creation in the modern economy, Michael McLeay, Amar Radia and Ryland Thomas of the Bank’s Monetary Analysis Directorate, Q1 2014

Bank for International Settlements:

Annual Economic Report, 2018: Cryptocurrencies: looking beyond the hype pp. 91-114

European Central Bank:

Federal Reserve of St Louis:

HM Treasury

Cash and digital payments in the new economy: summary of responses, HM Treasury, May 2019

The production and distribution of cash, The Auditor and Comptroller, HM Treasury, Bank of England, The Royal Mint, Financial Conduct Authority, Payment Systems Regulator, September 2020

Positive Money:

How is money really made by banks? - Banking 101 (Part 3 of 6), December 2012, Transcript, Full Series

Other:

25 years of £2 coin, M&G Bond Vigilantes, June 2023

This stackexchange discussion

The first record of coins being minted in Britain is attributed the Cantii, a Kentish tribe, c. 80–60 BCE. After the Roman conquest Britain in AD 43, official mints were established and coinage became more widespread. The first notes were issued by private banks and, until the middle of the 19th century, privately owned banks in Great Britain and Ireland were free to issue their own banknotes. Issuing powers of the banks were gradually restricted until the Bank Charter Act 1844 gave exclusive note-issuing powers to the central Bank of England. Under the Act, no new banks could start issuing notes; and note-issuing banks gradually vanished through mergers and closures. The last private English banknotes were issued in 1921 by Fox, Fowler and Company, a Somerset bank. Until 1931, the banknotes issued by the Bank of England could be exchanged, on demand, for the equivalent amount of gold. But the link between banknotes and gold, known as the Gold Standard, ended in 1931. Since then, banknotes have been a form of 'fiat money': money that is not convertible to gold or any other asset.

A note on terminology: I use the word ‘cash’ interchangeably with the word ‘money’. ‘Currency’ also loosely correlates to ‘money’. In my lexicon, ‘physical money’ is equivalent to ‘physical cash’; ‘digital money’ to ‘digital cash’. Likewise, ‘digital’ and ‘electronic’ are synonymous in my usage.

Here, I show an image of the oldest known coinage. Neiburger and Spohn, writing in Central States Archaeological Journal (October 2007) posit that fragments of hammered copper of irregular shape (which they refer to as ingots), dating from approximately 7,500 BC and found around Michigan and Wisconsin, which are often assumed to be 'scrap or damaged pieces not fit for implement manufacture', were in fact used as primitive coins. Their claim is based on the size and shape of the ingots accurately corresponding to that of the majority of other coinage used throughout history, but their evidence is speculative, and their claims have not been widely accepted by other researchers. Neiburger, E.J.; Spohn, Don (2007). "Prehistoric money". Central States Archaeological Journal. 54 (4): 188–194

The cash system is large and complex. Coins are produced for the whole of the UK by The Royal Mint (the Mint) under a contract with HM Treasury. The Bank of England (the Bank) produces notes for use throughout the UK. Designated commercial banks also produce notes in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Cash is distributed across the country by major commercial wholesale operators, comprising the major banks and Post Office Ltd. There is also a large network of commercial companies operating local cash centres to store cash, transport cash and operate the network of free-to-use and pay-to-use cash machines. Running the United Kingdom cash system incurs costs for both taxpayers and businesses. The production costs of notes and coins are offset by income resulting from their sale to the market at face value. In 2019-20, the Bank incurred note production and distribution expenses of £119 million and HM Treasury incurred UK coin production expenses of £23.6 million. Research commissioned by the finance sector has estimated that the UK’s entire cash infrastructure (including cash processing and distribution for private businesses) costs around £5 billion a year. National Audit Office

Matt Levine’s descriptions of banking are the most articulate and concise that I have encountered. Here are my top three excerpts:

There are two ways to think of the primary function of banks. One is a financial model: Banks borrow short-term to lend long-term, they provide credit intermediation, they pool risk-averse savings to finance risky investments, etc.; stuff we have talked about a lot around here.

Money Stuff, Tuesday 25th July 2023

The point of a banking system is to transform risky loans (a bank's assets) into safe bank deposits (a bank's liabilities). The bank takes risk (with your money) to make loans to businesses and home buyers, but you don't take risk by depositing your money in the bank. Your money is safe, it's "money in the bank."

There is some sleight of hand here; that transformation is magical. Some of it is accomplished by diversification and prudent lending and regulation and ample bank capital; some of it is accomplished by deposit insurance and lender-of-last-resort support for banks; some of it is just, like, residual magic. Some of it is just belief; the banking system works because people believe that their deposits are safe.

Money Stuff, Tuesday 27th June 2023

My basic model of banking is that it is a socially beneficial trick. People deposit money in the bank, thinking that it is perfectly safe. The bank uses that money to make loans, which are risky. It is good for society, and for economic growth, if people can get money to take risks, but the people who have the money often do not want to take risks with it. The bank is a magic trick that allows risk-averse savers to fund risky projects. Like any magic trick, it requires a certain suspension of disbelief: You can’t just tell people “the way it works is that we take risks with your money, but we tell you it’s safe.” There are some genuine tools (capital, diversification, deposit insurance) to transform the risky loans into safe deposits, but there is also some residue of pure belief, and if people lose that belief then it stops working.

Money Stuff, Thursday 6th July 2023