This week’s topic is drawn from a vintage that may not appeal to some readers’ palates.

Today, I would like to consider the form of monetary policy called ‘quantitative easing’.

Known to friends as ‘QE’, it also goes by the sobriquets ‘loose’ and ‘unconventional’. It is best conceptualised as ‘asset purchase programmes’, but can be considered a form of money creation, perhaps ‘printing digital money’. Its inverse is ‘quantitative tightening’ (QT).

I will do my utmost to make this a pleasant experience, but it is inevitable that a piece of this nature will not be everyone’s cup of tea. Rest assured, literature, art, and music will return soon…

Disclaimer: Given the topic, I will highlight that the usual disclaimers apply. All posts are solely my own opinion. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed reflect the views of my employer.

Quantitative easing is a highly consequential, but very poorly understood, phenomenon. As with any arcane subject, QE is scrutinised by very few of us. Most reasonable people have far better uses of their time and resources than to concern themselves with the academic details of monetary policy. Even those that do study and practise these details have not reached a consensus.

Yet you, dear reader, should you choose to read along with my drivel over the next few instalments, will join me in attempting to decipher QE.

In today’s instalment, the first of several, I’ll describe the key tools of monetary policy and the origins of quantitative easing. Then, I’ll narrow our focus to consider specifically the quantitative easing programmes conducted by the Bank of England.

In subsequent instalments, over the coming weeks, I will explore the consequences of unconventional monetary policy. In particular, I will consider QE’s relationship with:

Inflation;

Inequality;

Carbon emissions;

Public debt costs; and,

Monetary policy independence.

In other words: in this first piece, I’ll state the objective facts, the timelines, and the market mechanics; and in the subsequent pieces, I’ll offer some more subjective commentary...

In short - this week’s instalment is pretty dry. That said, it does lay the groundwork for the following series of increasing revelatory discussions about the consequences of QE. So, if you are keen to learn about QE’s history and operational details, please do read on. If not, you may prefer to return next time for a more animating and disquieting read.

This subject ties together themes from several previous posts. These prior instalments may be worth perusing if you’d like to get more familiar with any of the following concepts:

The price of time and uncertainty. Discussing interest rates, the cost of capital, and the importance of time preference.

Visualising yield curves. Discussing bond securities, bond returns, and yield curves.

The mechanics of money. Discussing how money is created and destroyed, digital bank reserves, and electronic bank deposits.

So, pour yourself a long draught of the strongest drink you have to hand. Hopefully, we are now armed and ready…

Let’s begin.

Monetary Policy Tools

Monetary policy describes the decisions taken by a central bank to influence monetary and financial stability.

The Bank of England (BoE) is the United Kingdom’s central bank. The Parliament of the United Kingdom has given the BoE statutory authority to pursue its mission, defined as promoting the good of the people of the UK by maintaining:

Monetary stability, which means keeping the prices of good and services stable and upholding confidence in the currency. (The Bank assesses the stability of prices using a measure of inflation and aims to keep that inflation measure at 2% per annum).1

Financial stability, which means ensuring that the UK’s financial system is resilient to any risks and shocks, such as, wars, asset price bubble collapses, pandemics, or banking crises. (The Bank’s target here is simply to avoid instability).2

What is the key tool in the monetary policy toolkit?

The Bank of England states that:

QE is one of two tools we can use to change interest rates. The other is the Bank Rate, which historically has been our most important tool.

Bank of England, Quantitative Easing

Without a doubt, the key tool that a central bank has at its disposal for implementing monetary policy is the ‘Bank Rate’, a type of interest rate.

Before we start a discussion about quantitative easing, we need to be comfortable and familiar with this interest rate.

So, what is an ‘interest rate’?

There are a vast variety of interest rates out there. What they all have in common is that they measure the price of time and uncertainty. An interest rate can be agreed between all manner of different entities, but to cite an example, think of a credit card user and their high-street bank.

For the purposes of this discussion, however, we are concerned with a very specific type of interest rate - the interest rate set by a central bank.

In the United Kingdom, this central bank interest rate is agreed at a monthly meeting held by a committee of senior policymakers at the Bank of England known as the ‘Monetary Policy Committee’ (MPC). It is the aforementioned Bank Rate, alternatively termed the ‘Prime Base Rate’ or ‘Official Rate’. I’ll also refer to it as the ‘central bank interest rate’.

By decreasing or increasing the central bank interest rate, general consensus is that the central bank can stimulate or constrict economy activity. The basic idea is that, by changing the interest rate, one can affect economic activity by altering the supply of money (how much credit creation bankers are willing to do in the economy) and the cost of capital (how much it costs people and businesses to finance new projects). I am brushing over enormous detail and nuance here, but we needn’t get bogged down with that too early.

But, what actually is this central bank interest rate, how does it work?

Mechanically speaking, the central bank interest rate is the prevailing lending rate that the central bank pays on cash deposits that qualified institutions (like commercial banks) hold in their accounts at the central bank.

That’s quite wordy, so maybe think of it like this: if you are a big bank and need to store all your spare cash somewhere overnight, you do so in your account at the central bank. The rate you are paid on that money overnight is the central bank interest rate. It is usually quoted as an annualised figure.

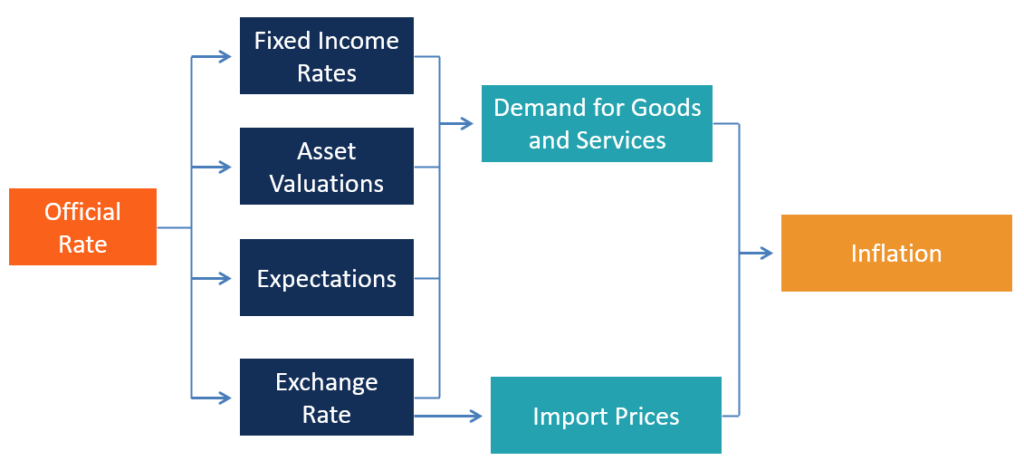

In turn, this central bank interest rate affects the rates charged and paid across the wider economy, since those financial institutions with accounts at the central bank react to changes in the base rate. In diffuse ways, these changes seep across the economy and influence the rates on fixed income assets, exchange rates, expectations of price changes, and the broad-based cost of capital. This process by which a change in the interest rate spreads out across the economy is known as the interest rate transmission mechanism.

To bring this to life, think of how you yourself could play a part in the transmission mechanism. Say that interest rates are going up and you find that your savings account no longer offers a competitive interest rate relative to other savings accounts advertised by comparable banks. Seeing this, you choose to move your savings to a bank with a higher interest rate savings account. In doing so, you are furthering the effect of the central bank interest rate. (Note: as always, this is not investment, financial, or any other form of advice).

How long does it take for a change in the interest rate to take full effect?

As you can probably already sense, the interest rate is an extremely blunt and indirect tool. Its effects are lagged, uncertain, and time-varying.

This is not at all ideal, however, the interest rate is also the only available tool that has a track record of impacting an economy. Interest rate transmission lags, the time it takes between the interest rate changing and its full effect being felt, are currently a topic of fierce debate amongst financial market participants.

Some of the impact of an interest rate change will be felt immediately by the real economy. A proportion of loans, mortgages, and other forms of debt are linked to the central bank interest rate, ‘floating’ at a rate above it, and will change in lock-step with the Bank Rate.

But many of the impacts of an interest rate hike are more lagged. Popular wisdom says that interest rate hikes take roughly 18-24 months to have its full impact the economy. No-one knows for sure how long it will take this time round (the current hiking cycle began in March 2022 in the US and December 2021 in the UK). As mentioned before, these interest rate changes are not only lagged, but also uncertain and time-varying…

Jerome Powell: Older academic literature says [interest rates take] a year or two to impact activity and another a year for inflation, new literature says its much faster… I do not think we know at this stage which it will be.

Chair of the Federal Reserve of the United States, ECB’s Central Banking Forum, Sintra, Portugal, June 2023

On this theme, current Bank of Japan Governor, Kazuo Ueda, recently cracked a seriously top-drawer central banker joke:

Moderator: Governor Ueda, do you worry about the lagged impacts of [other central banks’] policies on your economy?

Kazuo Ueda: Oh yes, but in Japan, we have not had any serious monetary tightening in three decades. I was a board member of the BoJ in 1998, at that time the policy rate was about 0.2-0.3%, today it is -0.1%. So in terms of that, the lag in the effects of monetary policy could be at least 25 years…

Governor of the Bank of Japan, ECB’s Central Banking Forum, Sintra, Portugal, June 2023. You can enjoy it in video form here (timestamp 6:21:00 to 6:21:40).3

So, that’s the central bank interest rate.

More monetary policy tools

To re-purpose that Churchill quote about democracy, interest rates are the worst monetary policy tool, except for all the others that have been tried.

On the theme of other tools that have been tried, here are several monetary tools that central banks have been known to use to influence monetary policy:

Mandating bank reserve requirements. Central banks can mandate that commercial banks maintain a certain percentage of their deposits as reserves. By adjusting these requirements, central banks can influence the amount of money banks lend out, thereby affecting the money supply and liquidity in the economy.

Purchasing assets. Central banks can buy or sell government securities, such as treasury bonds, in the open market to influence the money supply and interest rates. In the simplest possible terms, buying securities injects money and adds liquidity into the system, while selling them withdraws money (and still adds liquidity). When this is done at a small scale, it is known as open market operations (OMO). When asset purchasing is done at a large scale, it is called quantitative easing (QE).

And there it is - QE!

The Invention of Quantitative Easing

In my view, the best way to understand QE is to establish how it came into being. So I’ll begin by describing the origins of quantitative easing.

Until very recently, central bank interest rates had experienced a multi-decade decline from above 10% down to less than 1%. From the 1980s onwards, central bankers consistently reduced base interest rates in order to pursue their monetary policy objectives.

Illustrative example here, the United States central bank interest rate (plotted from the 1950s to 2021):

Compare the United Kingdom base rate (note the much longer time series, from 1700s to 2021):

What may not be immediately apparent is the following: as interest rates fall towards 0%, they appear to become incrementally less effective (as a tool for influencing economic activity and money supply).

Not only is this very unsporting of interest rates, but its also a serious issue for policymakers. Interest rates are, after all, the only monetary policy tool with a track record.

The same sort of tailing off seems to happen on the way up too - when interest rates go significantly higher than a certain range, their effects appear to become less pronounced.

Another way of putting this is to say that the effects of the interest rate as a tool of monetary policy are non-linear. One explanation for this is that interest rates have a natural level, sometimes referred to by economists as the neutral interest rate, or R*, and their efficacy diminishes when they too greatly exceed or lag the natural rate.

So, as interest rates sunk towards zero in the early 2000s, central bankers went hunting for new, unconventional tools to deploy in addition to, or instead of, interest rates…

Monetary experimentation in Japan

The first central bank to go on the hunt was the Bank of Japan.

Japan is something of a canary in the coal mine for developed economies. Most likely as a result of its ageing population, the Japanese economy has increasingly experienced stagnating growth and structurally low inflation (bordering at times on deflation).

Due to these macroeconomic dynamics, the Japanese central bank has kept interest rates near the zero bound since the late 1990s in order to stimulate the economy. In doing so, it discovered relatively early on that extremely low interest rates had a diminishing incremental effect towards the zero bound.

The search was further accelerated by the Japanese asset price bubble burst in 1991.

Japanese central bank interest rate (since 1950s, showing over two decades of extremely low rates):

Japanese economic activity (in GDP, suggesting stagnating productivity):

Japanese inflation (using consumer index - too low for comfort):

Japanese population pyramid (very top-heavy, reflecting a high ‘dependency ratio’):

Following an influential paper published in 1995 by economist Richard Werner, the Bank of Japan landed on a novel policy — quantitative easing:

Richard Werner: I first proposed the policy of QE in 1995 when I was the Chief Economist at a bank in Tokyo… QE was a tool designed to get out of banking crises quickly…

QE Infinity, Richard Werner Interview, 2021, Renegade

It is instructive to dig further into to Werner’s original paper to understand why he originally proposed QE as a policy for Japan.

Writing in 1995, Werner noted:

Since 1991 some 60,000 companies have gone bankrupt, to the tune of 32 billion yen. The banks have been landed with bad debts that I estimate at about 20% of annual GDP… Banks have become much more risk-averse, raising the standards that loan applicants must meet in order to obtain a loan. As a result, small and medium-sized enterprises have no longer been receiving sufficient funding.

In such a situation the single most vital policy is for the government to act and focus on increasing total purchasing power in the economy. Put simply, the central bank can print money and purchase assets in the markets from participants beyond the banking system.

In these ways, the central bank can inject new purchasing power in the economy. If this were done, then the overall amount of purchasing power in the economy would increase and commercial transactions throughout business would be revived.

In short, this policy aims to quantitatively increase credit creation in the economy for GDP transactions.

Keiki kaifuku, ryōteki kinyū kanwa kara, (How to Create a Recovery through ‘Quantitative Monetary Easing’), 1995, Richard Werner (translated John Cooke) & QE Infinity

And there we have, from Werner himself, in the very first description of QE, a rather tidy definition: printing money to purchase assets with the aim of injecting new purchasing power into the economy.

I’ll return to this shortly.

Though unconventional, QE was not an entirely alien concept to the BoJ. Central bankers had previously been known to purchase assets in order to support banks that were short of cash during times of financial instability, the aforementioned ‘open market operations’ (OMO).4 QE was different only in its scale - it was an asset purchase programme of a size never before seen.

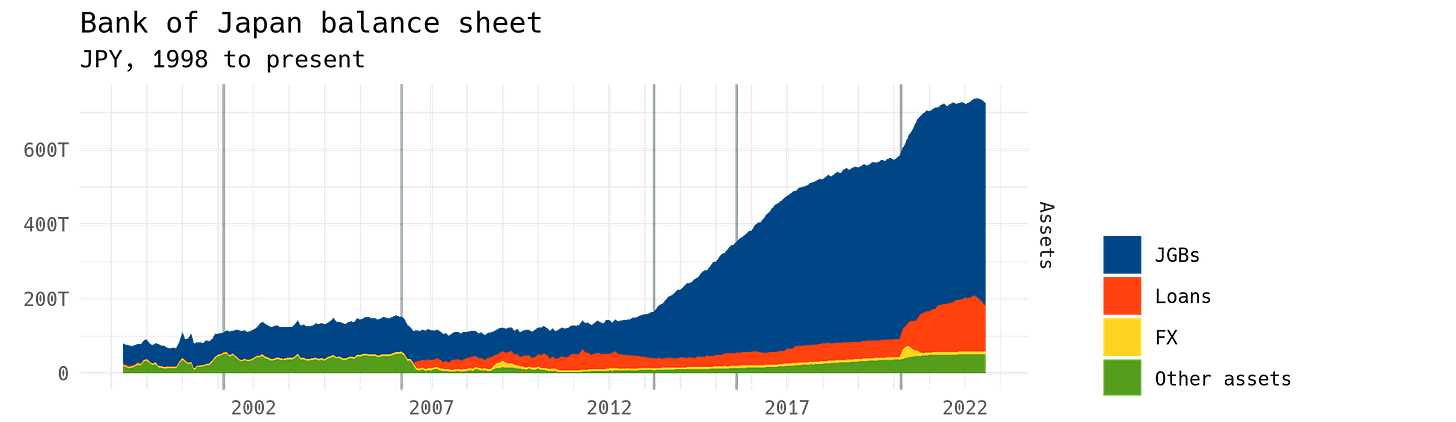

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) first introduced QE in March 2001 and this initial programme of QE lasted until March 2006. It was later renewed and continues to this day.

Illustrated below is the BoJ’s balance sheet assets (from 1998 to 2022) - reflecting quantitative easing asset purchases, consistently growing and expanding into assets beyond simply government bonds:

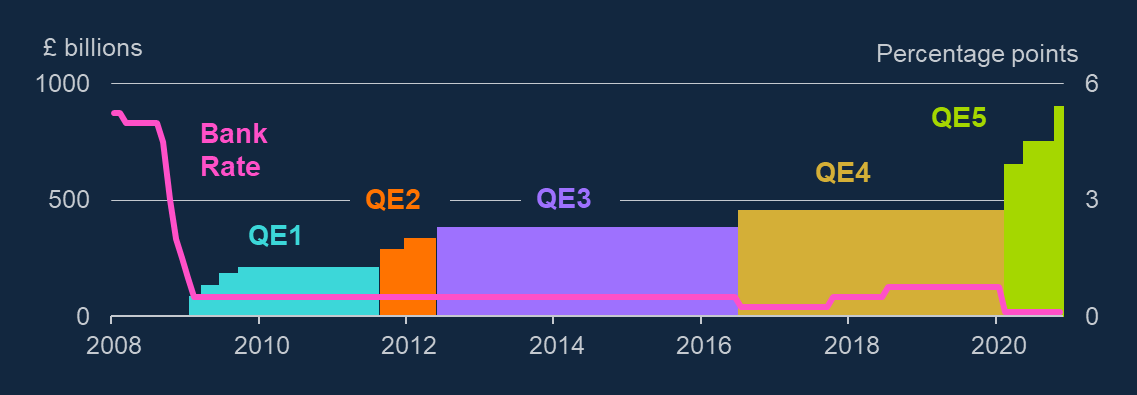

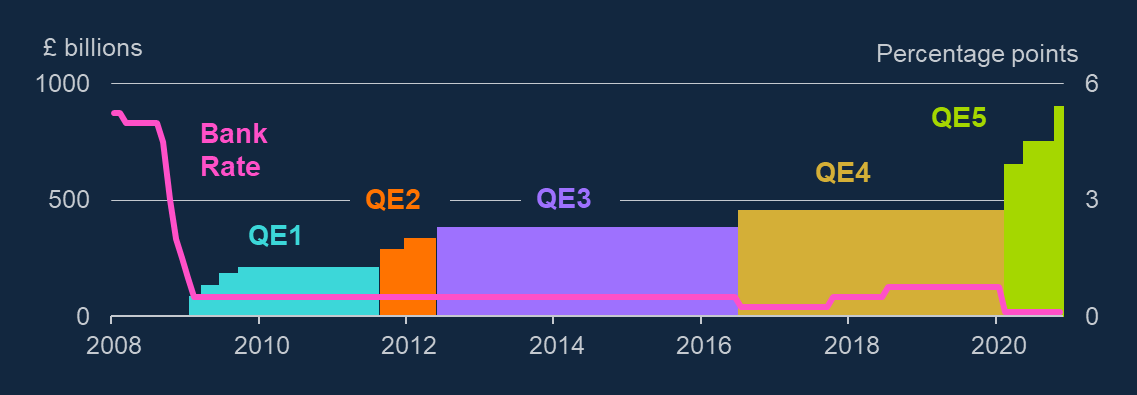

For most central banks, including the Bank of England, it was only in the face of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis that interest rates began to lose their effect:

We [the Bank of England] first began using QE in March 2009 in response to the Global Financial Crisis.

At that time Bank Rate was already very low. In fact, it couldn’t be lowered any further at that point. So we needed another way to lower interest rates, encourage spending in the economy, and meet our inflation target.

Bank of England, Quantitative Easing

And so, in 2009, the BoE embarked on its own programme of unconventional monetary policy in the form of large-scale asset purchases.

The phases of the Bank of England’s QE are illustrated here (hat-tip to the BoE for the neat graphic design):

Defining quantitative easing

We have, so far, established that QE involves printing money to purchase assets with the aim of injecting new purchasing power into the economy.

But what does that actually mean? In terms of market mechanics, what actually *is* quantitative easing?

Literally what QE involves is a central bank purchasing assets in the market:

QE typically involves purchasing longer-dated gilts from financial market participants in the secondary market in return for newly created central bank reserves.

At a high level, similarly to a Bank Rate cut, these asset purchases should lower longer-term gilt yields and other interest rates, thereby reducing borrowing costs for households and corporates and stimulating spending and investment.

Bank of England, Quarterly Bulletin 2022 Q1

In effect, by purchasing assets off market participants, the central bank aims to encourage those participants to buy other risk assets, thereby stimulating the economy and lowering the cost of capital for companies.

The specific mechanics of this process are more convoluted than the somewhat simplistic description that I offered above would suggest.

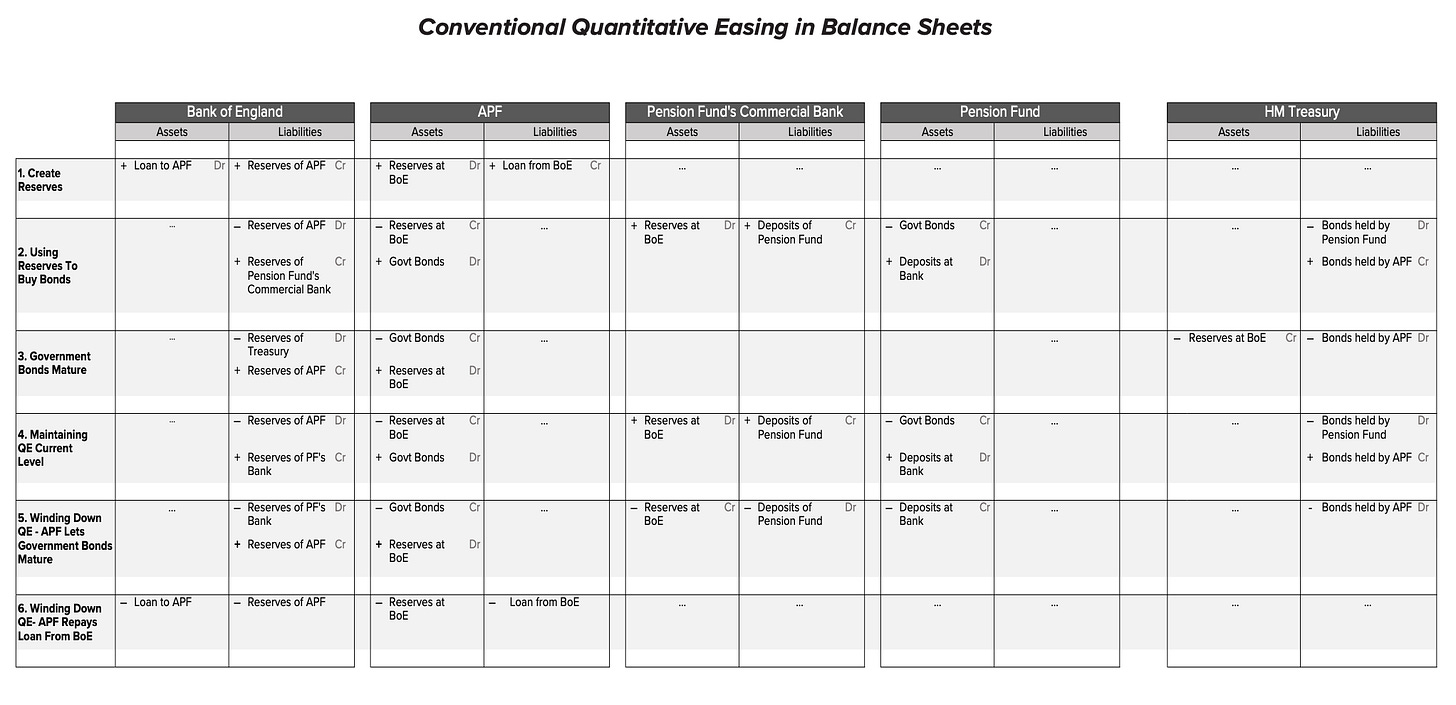

To expand further on the details, here is my most succinct, while still complete, summary of the mechanics of QE in the UK (for the morbidly curious, in Appendix 1, I present a full in-depth description of how QE is performed in the United Kingdom):

The mechanics of QE

The Bank of England creates new central bank reserves.

The BoE lends those new reserves to a special purpose entity called the Asset Purchase Facility (APF).

The APF performs QE by entering the market and using the reserves to buy bonds from other market participants via brokers known as GEMMs (gilt-edged market makers).

The market participants receive cash in return for their bonds which they are free to use (e.g. to buy more riskier assets), meanwhile, the APF now owns their bonds.

Once the APF has acquired a large portfolio of bonds through QE, it has three further options:

When the bonds begin to mature, they can buy more bonds to replace them (maintaining QE);

Allow the bonds to mature (unwinding QE); or

Sell the bonds back to market (quantitative tightening QT).

Those ‘three further options’ are particularly crucial and will be a focus for us when we consider the consequences of QE.

To offer a concrete example of an instance of QE, consider the following:

Say we buy £1 million of government bonds from an asset manager. In place of those bonds, the asset manager now has £1 million in cash. Rather than hold on to that cash, it might invest it in other financial assets, such as shares.

In turn, that tends to push up on the value of shares, making households and businesses and other financial institutions that own those shares wealthier. That makes them likely to spend more, boosting economic activity. Higher prices for corporate bonds and shares also lowers the cost of funding for companies and this ought to increase investment in the economy.

Bank of England, Quantitative Easing

That is a nice, tangible way to think about how QE might lower the cost of capital for businesses and stimulate economic activity.

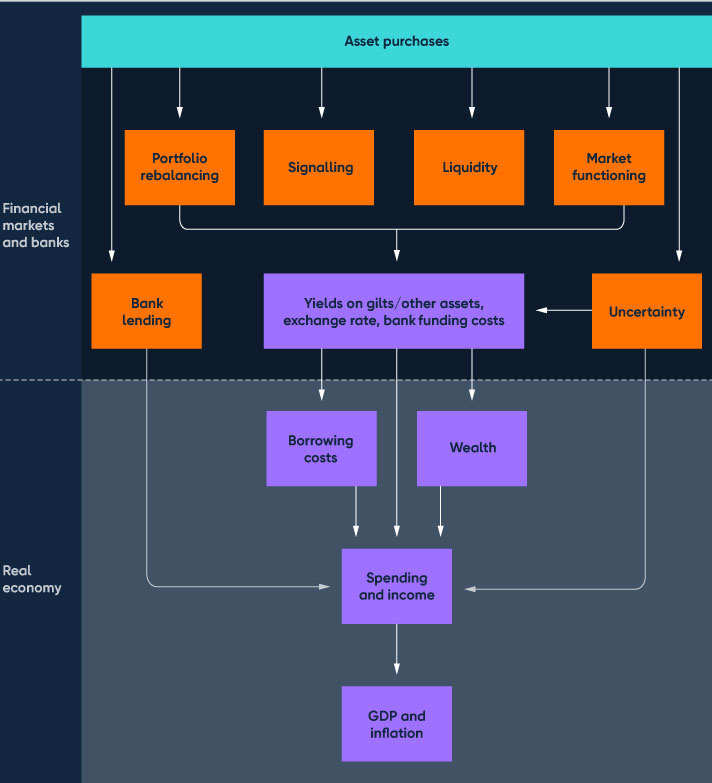

But, much like the interest rate mechanism, QE appears to influence economic activity via a complex series of channels that can be thought of as a transmission mechanism.

QE transmission mechanism

To abstract away from our concrete example, consider the following schematic framework, an interpretation of how QE affects the economy from a report published by the Bank of England:

Perhaps this appears impenetrable? The mechanism it claims to represent is certainly not straightforward.

I’ll attempt to digest it in a moment below, but you should know that this chart is a significant improvement on prior attempts to visualise QE transmission. See, for example, this monstrosity:

In the BoE schematic, the top of the chart shows asset purchases, which travel down the chart via multiple routes, flowing through financial markets and banks before reaching the real economy, where they ultimately impact GDP and inflation.

In their descriptions of quantitative easing’s effects on the economy, the BoE foregrounds the left-hand side of this schematic, i.e. the channels by which QE acts as a tool for monetary stability:

Quantitative easing is a tool central banks can use to meet an inflation target. The aim of quantitative easing is to inject money into the economy in order to revive nominal spending.

Bank of England, Quantitative Easing & Benford et al. (2009)

These channels of monetary stability are identified as follows:

QE can lower the expectations component by conveying information about the future path for the policy rate (signalling channel). QE can also lower term premia via several channels. By shrinking the supply of longer-term bonds, QE can push some investors to rebalance their portfolios towards other bonds and thereby lower their yields, as well as increasing the price of other assets (portfolio balance channel)… And under some conditions QE can stimulate credit supply by increasing banks’ holdings of reserves (bank lending channel).

Bank of England, Quarterly Bulletin 2022 Q1

However, as Bailey et al also illustrate on the right-hand side of the above schematic, QE can also serve as a tool of financial stability:

QE can also reduce any liquidity premia on purchased assets (liquidity channel). In stressed circumstances, QE can improve market liquidity more broadly by lowering risks to dealers who are intermediating trades (market functioning channel). In addition, QE can mitigate uncertainty in financial markets and the real economy (uncertainty channel), which may also reduce term premia, as well as having wider effects.

Indeed, when QE was first implemented by the BoE, it was partly in response to a lack of liquidity in markets in 2009. When market participants are less willing to trade, liquidity dies up. In those conditions, a central bank that enters the market with QE and provides additional liquidity is acting as a ‘lender of last resort’ of sorts by taking the other side of transactions.

And that, more or less, is QE.

Closing thoughts

This topic is undeniably dense and it is quite possible that my written description is insufficient and imprecise. For that reason, if you would like to clarify anything that I have written about here, or are simply interested in digging deeper into any of the technicalities raised by this topic, please do not hesitate to get in touch. As you can probably already tell, I will be delighted to talk with you at any length on this theme.

Here, for instance, are two examples of questions that you may wish to clarify:

Is it only government bonds that central banks purchase during QE?

Generally yes, QE programmes purchase government bonds. For the Bank of England, that means UK long-term government bonds.

That said, from 2016 onwards, the Bank of England did begin to buy increasingly risky assets. Primarily, this was investment-grade corporate debt (to be specific, sterling-denominated, non-financial, investment-grade corporate bonds).

As of 6th June 2023, the Bank of England’s Asset Purchase Facility has completed the sale of corporate debt. In other words, it has completed its quantitative tightening of the corporate bond portfolio. The quantitative tightening of the government bond portfolio is ongoing. Even more so than QE before it, QT has almost entirely escaped any scrutiny from either the media or the political class. This is genuinely surprising given the vast consequences it has on our public finances. More on this next time.

In total, we bought £895 billion worth of bonds. Most of those (£875 billion) were UK government bonds. The remaining £20 billion were UK corporate bonds.

Bank of England, Quantitative Easing

This sale was intended to completed earlier, but was delayed by the LDI crisis that followed the Liz Truss Conservative government’s so-called ‘Mini Budget’. For a complete timeline of the Bank of England’s quantitative easing operations, please refer to Appendix 2.

On the subject of types of asset purchased, I would also note that the Bank of Japan has frequently bought corporate debt, extending its purchases to even loans and equity securities - so far, the most unorthodox asset purchase of the Bank of Japan’s unorthodox monetary policy has been its purchases of Japanese equity ETFs totalling JPY37tn ($260bn, as at the end of July 2023).

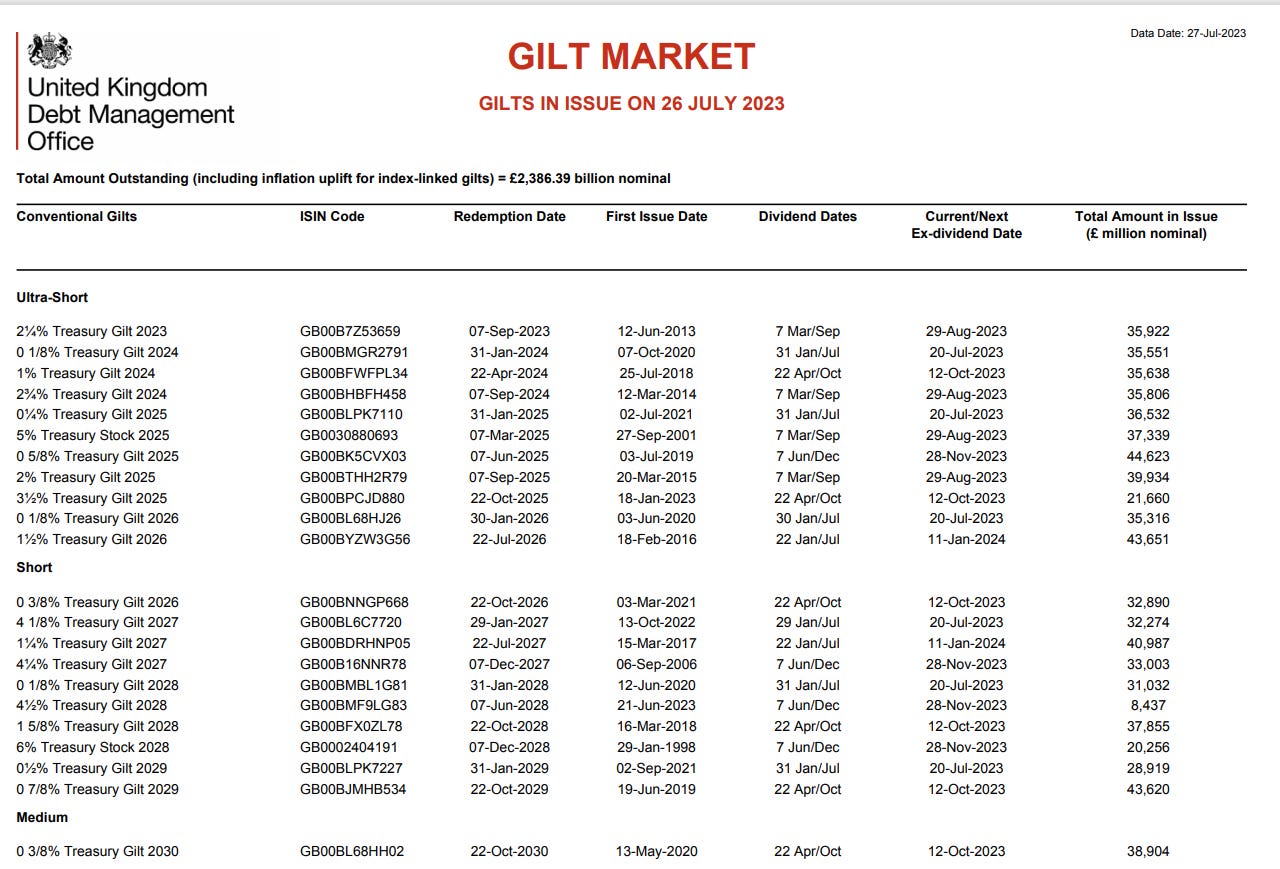

How does the APF conduct asset purchases?

The APF buys and sells assets through brokers known as gilt-edged market makers (GEMMs) in the secondary market.

The Debt Management Office (DMO), which is the government body that organises the sale of the UK’s public debt in the primary market (where it is first announced and sold), provides a full list of qualified GEMMs here. In Appendix 3, I include a snapshot of all the UK government bonds currently in issue as listed by the DMO.

One point to note here is that, when asset purchases are conducted, those GEMMs make some degree of profit through the additional trading that the QE generates.

For anyone interested in further specific operational details of asset purchases and sales, there is a detailed Q&A available here that describes, for instance, the discriminatory price auction and bidding process by which the APF’s gilt sales are conducted as part of quantitative tightening,

Next time…

So, there you have it. Those are the cold hard facts of quantitative easing; what it is, and how it works.

Next time, we can start to dig into the really fascinating and emotive parts of the conversation around quantitative easing - its consequences, intended, or otherwise.

There, you can expect to find some far more opinionated prose. For, having taken the time to examine the topic, it is only right that we bring to light the consequential and, far too often, deeply inequitable impacts of unconventional monetary policies.

As always, thank you for reading.

Bibliography

Office for Budget Responsibility

The Office for Budget Responsibility was created in 2010 to provide independent and authoritative analysis of the UK’s public finances. The OBR produces detailed five-year forecasts for the economy and public finances twice a year. The forecasts accompany the Budget Statement (usually in late November) and the Spring Statement (usually in March). They incorporate the impact of any tax and spending measures announced in those statements by the Chancellor. The following pieces were instrumental to my understanding of this subject:

The fiscal impact of quantitative easing and quantitative tightening, March 2023

The fiscal impact of the Asset Purchase Facility, July 2021

Debt maturity, quantitative easing and interest rate sensitivity, March 2021

The direct fiscal consequences of unconventional monetary policies, March 2019

Bank of England

Despite its many flaws, the Bank of England should be lauded for its ability to create excellent analysis and criticism of its own policies. These pieces are invariably of the highest quality, objective, and are occasionally even concise:

Quarterly Bulletin 2022 Q1 - Quantitative easing at the Bank of England: a perspective on its functioning and effectiveness, May 2022

Quantitative Easing, June 2023

Market Operations Guide: Our tools, May 2023

Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme: Eligibility and sectors, September 2016

Market Notice: Asset Purchase Facility (APF) corporate bond purchase scheme reinvestment programme, November 2021

Benford, J., Berry, S., Nikolov, K., Young, C., and Robson, M. ‘Quantitative easing’. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, Volume 49, 2009

Philip Bunn, Alice Pugh and Chris Yeates. ‘The distributional impact of monetary policy easing in the UK between 2008 and 2014.’ Staff Working Paper No. 720, March 2018

Minutes of Bank of England call with GEMMs on its provisional approach to APF gilt sales, August 2022

Monetary Policy Committee

Andrew Bailey. Speech at Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium. The central bank balance sheet as a policy tool: past, present and future, August 2020

Silvana Tenreyro. Speech at the SES Annual Conference Glasgow. Quantitative easing and quantitative tightening, April 2023

The House of Lords, Economic Affairs Committee

This House of Lords committee has produced a valuable body of analysis on the topic of quantitative easing. I came to read their final report relatively late on into my own independent research process and was struck, concerned even, to discover that it had reached an almost identical set conclusions to me:

Quantitative easing: a dangerous addiction? 1st Report of Session 2021–22

Written evidence submitted by Professor Richard A. Werner

In Focus: Quantitative Easing, Chris Smith, November 2021

Richard Werner

How to Create a Recovery through ‘Quantitative Monetary Easing’, in Keizai Kyōshitsu, 2 September 1995. English translation by John Cooke (November 2011)

Interview with Renegade. Transcript & Video, August 2021

Richard Werner’s Website, All Publications

Debt Management Office

Gilts in Issue

M&G Vigilantes

How will the reversal of loose monetary policy affect UK housing? Robert Burrows, July 2023

Cancel Culture – A New Monetary Phenomena. Richard Woolnough, May 2023

Return of QE? Editorial, September 2022

On the mechanics of QE:

Positive Money, How Quantitative Easing Works

Frank van Lerven, A Guide to Public Money Creation: Outlining the Alternatives to Quantitative Easing, May 2016

Joseph Wang, The Mechanics of Quantitative Easing & M2, August 2020

Brooks MacDonald, Quantitative Easing & Quantitative Tightening, 2021

Center for Financial Stability, A Story of Money, Inflation, and the CFS Lawrence Goodman June 2023

Other readings:

Matt Levine, Markets are down for a reason, March 2020

CFA Institute, Stressed and Distressed Credit: Risk and Reward, June 2023

National Bureau of Economic Research, Time Consistency And The Duration Of Government Debt: A Signalling Theory Of Quantitative Easing, Saroj Bhattarai, Gauti B. Eggertsson, Bulat Gafarov, July 2015

Centre for Central Banking Studies, Understanding the central bank balance sheet.

Bloomberg’s Philip Aldrick. Tumbling Money Supply Alarms Economists Who Foresaw Inflation. April 2023

Deutsche Bank, Konzept, Can markets withstand the removal of QE? October 2017. October 2017

Chris Marsh, How big are Bank of England QE losses? July 2023

Financial Times reporting (£ paywall):

Measuring the Bank of England’s global-local dilemma. Costas Milas, July 2023. Delphine Strauss, July 2023

UK government faces £150bn bill to cover Bank of England’s QE losses

UK to run up highest debt interest bill in developed world. Mary McDougall, July 2023

The pros and cons of QE — part ∞. Robin Wigglesworth, February 2023

Does it matter that central banks are losing squillions? Aziz Sunderji, February 2023

How quantitative tightening *really* works. Tim Young, January 2023

RBC: The UK’s double indemnity danger. Louis Ashworth, October 2022

Rishi Sunak blamed for losing £11bn in servicing UK government debt. Chris Giles, June 2022

The case for continuing quantitative easing is hard to fathom. John Plender, August 2021

Payback time for QE looms — and it will be expensive. Merryn Somerset Webb, April 2018

Guest post: Central Bank Quantitative Easing as an Emerging Political Liability. Victor Xing FTAV, September 2017

Central banks hold a fifth of their governments’ debt. Kate Allen and Keith Fray, August 2017

The end of ‘QE infinity’? Gavyn Davies, October 2016

BoE corporate bond buying takes it deeper into the monetary mire. Neil Collins, September 2016

Record-breaking Bank of England. Robin Wigglesworth, August 2016

We are the QE generation — and it is quite a burden. David Oakley, January 2016

Bank of England’s QE through the looking glass, Neil Collins, September 2015

Merits of Bank of England’s QE still spark debate five years on. Chris Giles, March 2014

Osborne launches raid on QE surplus. Chris Giles, November 2012

Appendix 1: The Mechanics of the Bank of England’s Quantitative Easing Operations

I came across a full description of this process in the following report. I found this description pretty satisfactory as an explanation of the step-by-step mechanics. I summarise it in the Appendix below. (The source is: pp.38-39 )

Phase 1: Create reserves, the BoE creates digital reserves and loans them to the Asset Purchase Facility (APF).

BoE creates new digital reserves .

BoE loans these newly-created reserves to a separate entity, the Asset Purchase Facility (APF), a subsidiary of the BoE.

In this process, the BoE gains an asset (in the form of the loan to the APF), whilst simultaneously incurring a liability (in the form of the reserves owed to the APF).

Phase 2: Purchase assets, the APF purchases assets (usually bonds) in the market from the private sector.

The APF enters the market and uses the reserves to purchase bonds held by the private sector through market makers (GEMMs).

Via an intermediary broker, the APF swaps its assets (reserves) for the bonds held by private sector entities (such as pension funds and asset managers).

At the same time, the private sector sells assets to APF and receives cash

When the APF buys the asset, the reserves are transferred to the seller (e.g. the pension fund). The asset now sits on the APF’s balance sheet, while the pension fund now has more cash (the digital reserves which have now become commercial bank money, probably sat with a custodian in a bank deposit). Consequently, the digital reservces created by the BoE have now made their way into the economy in the form of digital bank deposits. Note also, the market maker takes a fee for the transaction.

Across this whole process, the balance sheets of the BoE, Asset Purchase Facility, and commercial banks have expanded by the amount of the asset purchase. The Pension Fund meanwhile has simply swapped a bond for deposits at a commercial bank. Interestingly, the Treasury’s liabilities remain unchanged except for the important fact that bonds that were held by the private sector are now held by the APF (and therefore by the BoE). Important not least because the interest now paid on this debt is given straight back to Treasury!

The previous arrangement was for these cash flows to accumulate on the APF's balance sheet. Because the APF is indemnified by the Government, any gains or losses it makes arc ultimately due to the Exchequer. So the gilt coupons received by the APF amount to payments from one part of the public sector to another. As the scale and likely duration of the APF has increased significantly since its inception, I agree that it now makes sense to normalise the cash management arrangements for the APF.

Phase 3: Continue to ease, unwind easing, or tighten

Once quantitative easing is up-and-running, it is necessary to manage the portfolio of assets that have been acquired. This is because, periodically, a certain amount of government bonds will mature. In other words, the issuer of the bond will be required to repay the principal amount.

Since most of the bonds are government bonds, the issuer that has to repay the principal is HM Treasury. This ends up in a situation where one part of the public sector, the Treasury, is paying another part of the public sector, the Bank of England’s APF, boatloads of money. Bonds also typically have coupons (the ‘interest’ on the bond), so throughout the time that the APF owns government bonds, the Treasury is paying bucketloads of money to the APF in the form of coupons.

To get back to the main theme, at some point, the BoE has to decide what to do as the bonds in the APF portfolio begin to mature. There are three options either (i) maintaining quantitative easing, (ii) unwinding quantitative easing, or (iii) quantitative tightening.

Maintaining Quantitative Easing, BOE (MPC) Orders APF to Reinvest Maturing Debt Held through APF into More Government Debt Held by Private Sector:

If the Monetary Policy Committee has chosen to ‘maintain QE at its current level’ (as opposed to reversing it) then the APF must rollover the government securities that it holds.

Following the above hypothetical example, the £20 billion of reserves that the BoE now holds is used to purchase more government bonds from the financial markets.

If the APF keeps buying bonds, then it is merely repeating the process highlighted in step 2 above.

The £20 billion of reserves are transferred back to the accounts of the banks, and the banks in turn create £20 billion of new deposits for the Pension Funds.

Since the Pension Funds would rather hold bonds than cash, they buy newly issued bonds from the Treasury and the £20 billion of reserves is transferred back to the Treasury’s account at the BoE.

Unwinding QE, the BoE orders the APF to cease from re-investing maturing debt:

If it were desirable to wind down QE, then the APF would simply stop repurchasing government bonds as and when they matured.

Accordingly, as the government bonds held by the APF matured, the Treasury would have to pay down its debt to the APF. The APF’s assets would change, gaining central bank reserves as the government bonds matured. The liabilities of the BoE would change; its liabilities (in the form of central bank reserves) to the Treasury would decrease but its liabilities to the APF would increase. The balance sheet of the Treasury contracts, its liabilities decrease as it has paid down its debt to the APF and its assets have decreased as it used central bank reserves to settle its debt.

‘Quantitative Tightening’, the APF sells back the assets and pays down the loan from BoE:

The APF would then pay back the BoE, reducing the balance of its central bank account (assets) and simultaneously reducing the amount outstanding on its loan (liabilities).

The corresponding assets and liabilities on the BoE’s balance sheet similarly reduce.

The simultaneous cancellation of the asset and the liability results in the destruction of central bank money.

Appendix 2: Timeline of Quantitative Easing in the United Kingdom

19 January 2009: Chancellor’s Statement announcing the intention to set up an asset purchase programme.

29 January 2009: Establishment of the APF Fund (Bank and HM Treasury).

9 November 2012 HM Treasury announces the transfer of gilt coupon payments to the Exchequer (Bank and HM Treasury).

4 August 2016 MPC agrees to expand the APF by launching a Term Funding Scheme (TFS) and a Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme (CBPS) (see exchange of letters between the Bank and HM Treasury).

19 March 2020 - In response to COVID-19 pandemic, MPC agrees to expand the APF with a £200 billion increase to the stock of UK gilts and sterling non-financial investment-grade corporate bonds to reach £645 billion. This was followed by the MPC deciding to expand the APF with a £100 billion increase in June 2020, and then a further £150 billion in November 2020, bringing the total stock of asset purchases to £895 billion.

3 February 2022 MPC votes to begin to reduce the stock of UK gilt purchases by ceasing to reinvest maturing assets, and the stock of sterling non-financial investment-grade corporate bond purchases by ceasing to reinvest maturing assets and by a programme of corporate bond sales.

21 September 2022 MPC votes to begin sales of the stock of gilts held in the APF.

6 June 2023 APF concludes sale of corporate bond book.

23 June 2023 APF is currently conducting sales of the gilt bond book.

Appendix 3: Gilts in Issue via UK Debt Management Office

The Monetary Policy Committee is the relevant body here, more on them shortly.

This effort is led by the Financial Policy Committee (FPC), supported by the independent regulatory body the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA).

The Central Banking Forum is extremely fun if you’re a monetary policy wonk - the main event is when all the world’s top central bankers get plonked on one panel and are asked tough macroeconomic questions by a wily journalist, hilarity naturally ensues…

Since then, the BoJ has branched out into other unconventional tools, most notably ‘yield curve control’ (YCC), one for another time.