Disclaimer: All my disclaimers apply here. All posts are solely my own opinion. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed reflect the views of my employer.

Doubtless readers of this Substack have not yet forgiven me for previously subjecting them to lengthy meditations on the cost of capital, the nature of money creation, the mechanics of quantitative easing and the UK public finances.

In the spirit of “a vigorous error vigorously pursued”, today, I will dare once again to return to the theme of debt capital markets.

Programming note: Pushing this out earlier than planned, ahead of the Spring Statement.

In this piece, I will examine whether there are any practical changes to the debt management strategy that the Bank of England and HM Treasury could implement via the Debt Management Office (DMO) to reduce government financing costs.

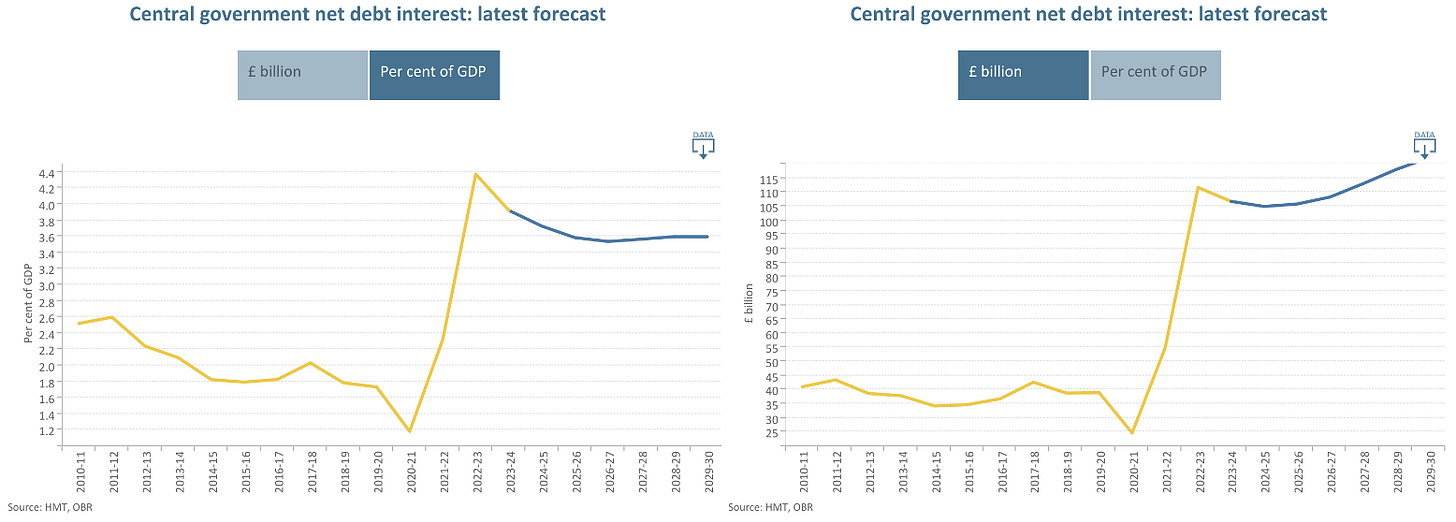

This subject is of particular relevance in the current environment because public debt interest servicing costs represent a significant and growing proportion of overall UK public expenditure (compare charts below).

Even marginal improvements in market efficiency could yield substantial fiscal benefits by further broadening the investor base and enhancing both primary and secondary gilt market functioning through strategic adjustments to issuance patterns and market structure.

Specifically, the debt management changes that I will consider are:

Issuance strategy:

Maturity profile;

Currency diversification;

Range of instruments

Green gilts & greenium

Sustainability-linked gilts.

Market architecture:

“Market maker of last resort” programme;

Strategic liquidity concentration.

In the course of this piece, I will also offer a commentary on particular characteristics of the gilt market and aspects of its historical development, including:

UK gilt market primer:

Primary issuance;

Physical secondary market;

Sterling interest rate derivatives;

Market participants and regulatory influences.

Yield curve dynamics:

Interest rate and inflation expectations;

Liquidity premium;

Term premium;

Credit default risk premium.

Gilt market structure primer:

Market structure (1688-1986);

Current market structure.

UK gilt market primer

Primary issuance

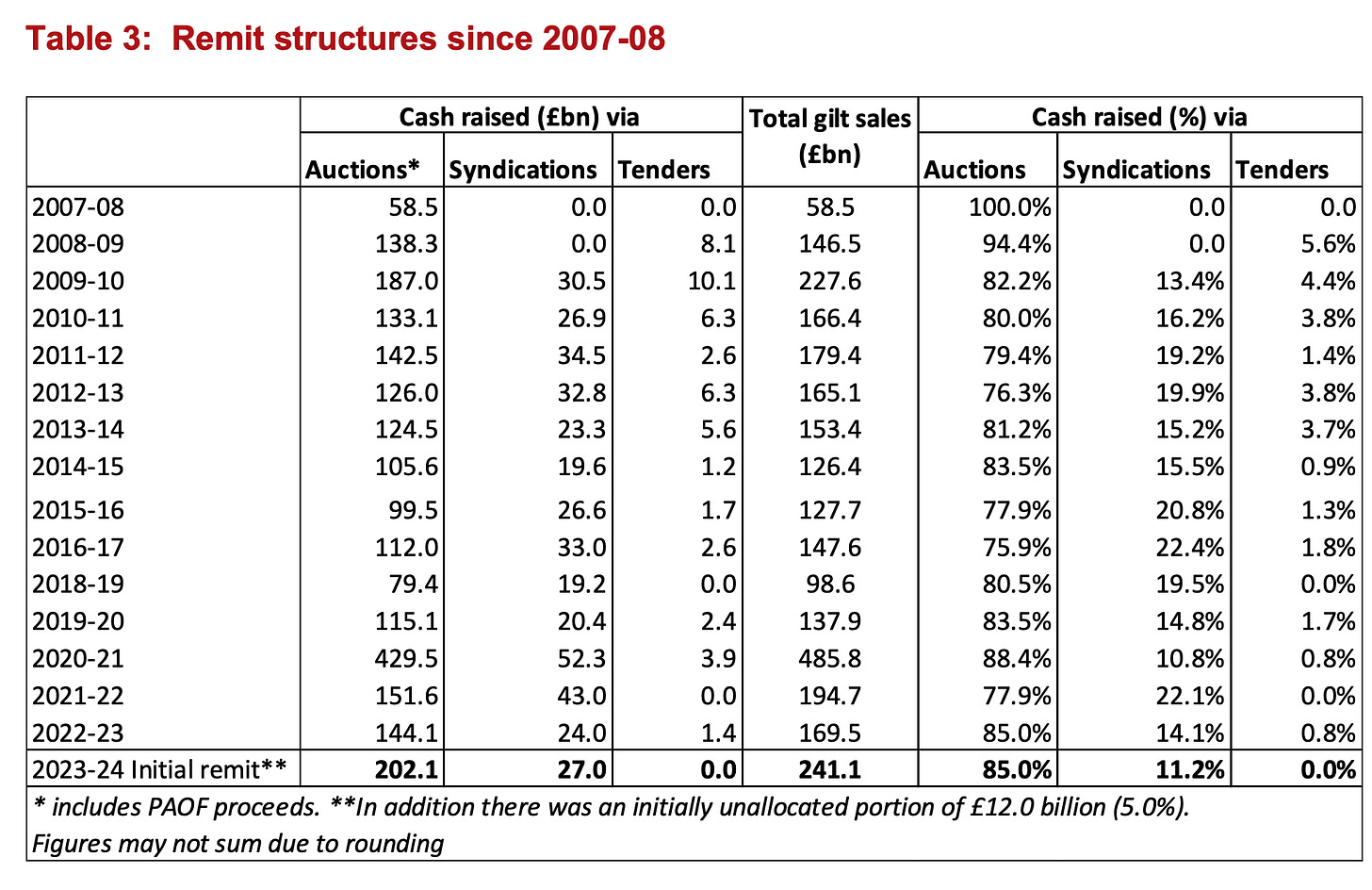

UK government bonds, known as gilt-edged securities, or gilts, are issued by the UK Debt Management Office (DMO) through a structured framework (auctions at predetermined times). HM Treasury establishes the annual financing remit alongside the Budget, determining gilt issuance volume and composition based on government borrowing requirements and debt management objectives.

Physical secondary market

The UK benefits from a deep and liquid physical sterling gilt market. That means that bond yields, while anchored by Bank of England policy rates, are continuously established by secondary market participants.

The markets for these gilts span the entire yield curve, from very short maturities (Treasury bills and short-dated conventional gilts) to ultra-long maturities (exceeding 50 years). This comprehensive coverage ensures efficient price discovery, reliable government funding access, and serves as a critical benchmark for sterling-denominated assets across the financial system. GEMMs maintain continuous two-way markets, though liquidity typically concentrates in benchmark issues at key tenors (2, 5, 10, 30, and 50 years), with off-the-run gilts sometimes trading less efficiently.

Sterling interest rate derivatives

Gilt derivatives are also highly liquid and complement the physical gilt market by offering superior capital efficiency, straightforward short positioning mechanisms, and precise risk management tools through a variety of instruments.1

These derivative instruments standardise interest rate exposure across the yield curve, reducing fragmentation while offering lower transaction costs and minimal price impact even for substantial positions. This efficiency attracts a broader set of market participants, including those unable to hold physical gilts due to regulatory constraints. This serves to enhance the overall functioning of the market to the extent that, during periods of stress, derivatives often become the primary venue for price discovery, providing debt managers and central bankers with essential signals about market expectations.

Market participants and regulatory influences:

The gilt market features a range of participants with distinct motivations.

Pension funds and insurance companies typically seek longer-dated gilts to match long-term liabilities, often operating within regulatory frameworks like Solvency II that encourage or mandate such matching. For example, a defined benefit pension fund might purchase 30-year gilts to align with future pension payments.

Asset managers approach the market tactically, adjusting duration and curve positioning to generate alpha. Hedge funds are similar and may also engage in relative value strategies like gilt-swap spreads or cross-market basis trades.

Overseas investors, notably, foreign central banks, hold gilts as reserve assets, typically in shorter maturities.

UK banks use gilts to maintain liquidity buffers to satisfy regulatory requirements like the Liquidity Coverage Ratio, using gilts as high-quality collateral for repo transactions, and supporting customer trading activity.t.

UK individuals access UK public debt through NS&I products and the DMO's with a focus on income generation from shorter-term issues.

The Bank of England itself holds a substantial gilt portfolio acquired through quantitative easing operations, peaking at £895 billion in 2021, which significantly influences market dynamics through both its accumulation and subsequent reduction phases.

Maturity profile

First, let’s consider the question:

Could the DMO reduce financing costs by changing the term structure (or the weighted average maturity) of the national debt?

To answer this satisfactorily, it is worth first considering the nature of the prevailing yield curve dynamics in the UK sovereign market.

Yield curve dynamics

In a purely theoretical world where government bond yields perfectly and exclusively describe the anticipated course of future central bank interest rate policy, a government’s funding strategy should be indifferent to where it issues across the yield curve.

In reality, however, bond yields are abstract and complex composite measures that incorporate not only investor expectations for future central bank interest rate actions, but also various other expectations such as inflation expectations. In the case of inflation expectations, the premium, known as the “break-even rate”, can be observed by comparing the nominal bond yield with the equivalent inflation-linked bond yield (the “real” yield).

Beyond rates and inflation, however, other components of yield typically remain impervious to direct observation. For instance:

Liquidity premium. Compensation for the difficulty or cost of quickly buying or selling a specific bond in the market. Relatedly, the supply and demand dynamics, how the volume of bond issuance and investor participation affect market pricing. Similarly, central bank intervention may also play a role, such as quantitative easing, quantitative tightening and other monetary policies interventions that distort bond yields.

Term premium. Compensation for duration risk, as in, the additional yield required for holding longer-maturity bonds, reflecting increased interest rate risk and uncertainty. Whereas interest rates and inflation can be observed after the fact, those other residual components of yields, such as term premium, remain unobservable even after the event and cannot be measured reliably, either independently or as a residual.

The credit default risk premium (the compensation demanded by investors for the risk that the issuer might not fully repay its debts) is another important component of yields. However, in the case of a sovereign issuer with monetary policy independence, such as the United Kingdom, are not typically material. Indeed, this premium, also termed the “credit spread”, is typically determined by comparing the yield of the issuer to the supposedly “risk-free” reference currency sovereign yield.

Compare, also, the hypothesised Moron Risk Premium.

Besides these, yields may be composed of a multiplicity of other factors that shape investor expectations.2

Why does the UK have a long-dated debt profile?

As a result of prevailing yield curve dynamics, sovereign issuers develop idiosyncratic maturity issuance profiles over time.

The UK, for instance, has maintained a pronounced long-dated bias in its debt maturity profile for several decades, influenced by various factors, including:

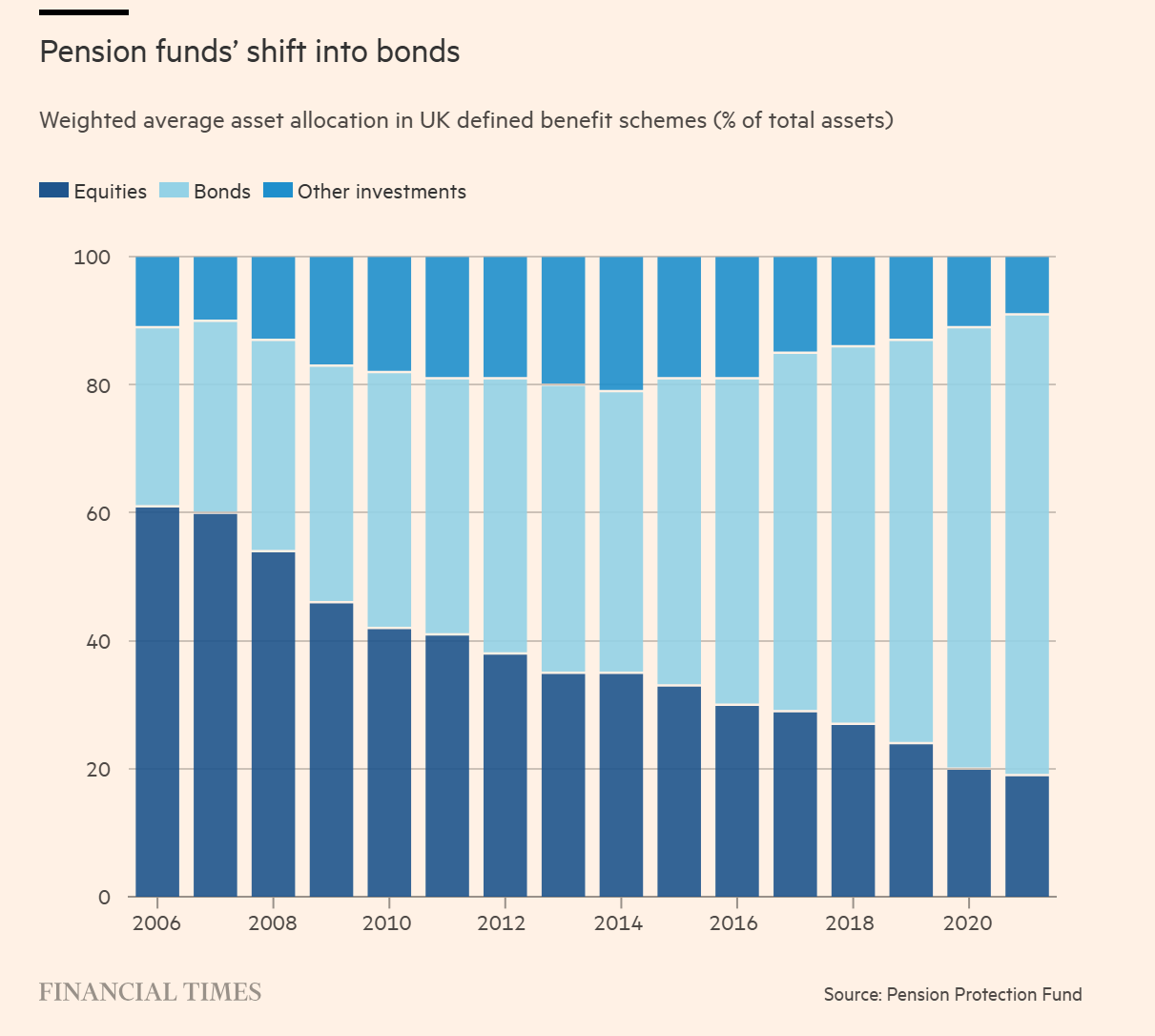

Pension demand: Prior to the global financial crisis, the UK yield curve exhibited an unusual inversion where 10-year gilts often yielded more than 30-year gilts—contradicting the conventional relationship between duration and yield. This anomaly reflected persistent structural demand from UK life insurers and pension funds implementing Liability-Driven Investment (LDI) strategies. HM Treasury rationally responded by shifting issuance towards longer maturities to meet this demand and capture favourable pricing for pensions seeking assets that match the duration of their liabilities.

“Refinancing risk”: The strategy of issuing long-dated debt is also motivated by a desire to avoid the uncertainty of refinancing short-term liabilities at potentially higher future rates, termed “refinancing” risk (see, for instance, DMO 2023/24 Review, Sections 2.18 & 2.19). By “locking in” known long-term borrowing costs, the Treasury seeks greater stability and predictability in debt servicing expenses.

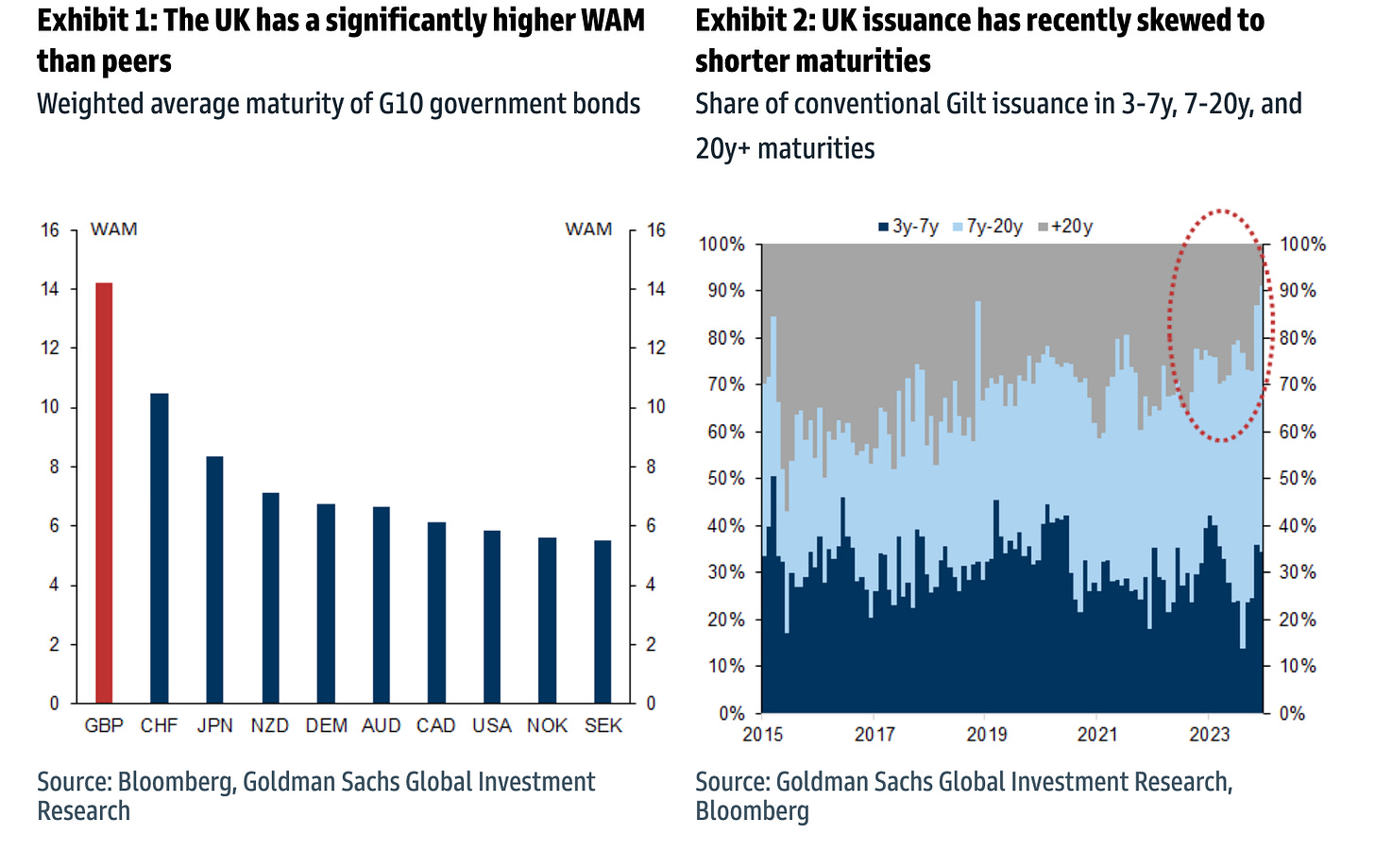

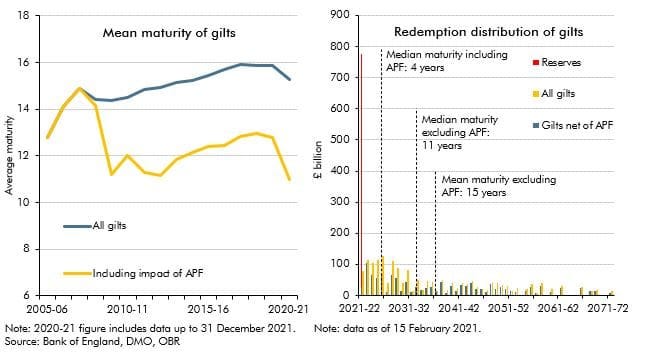

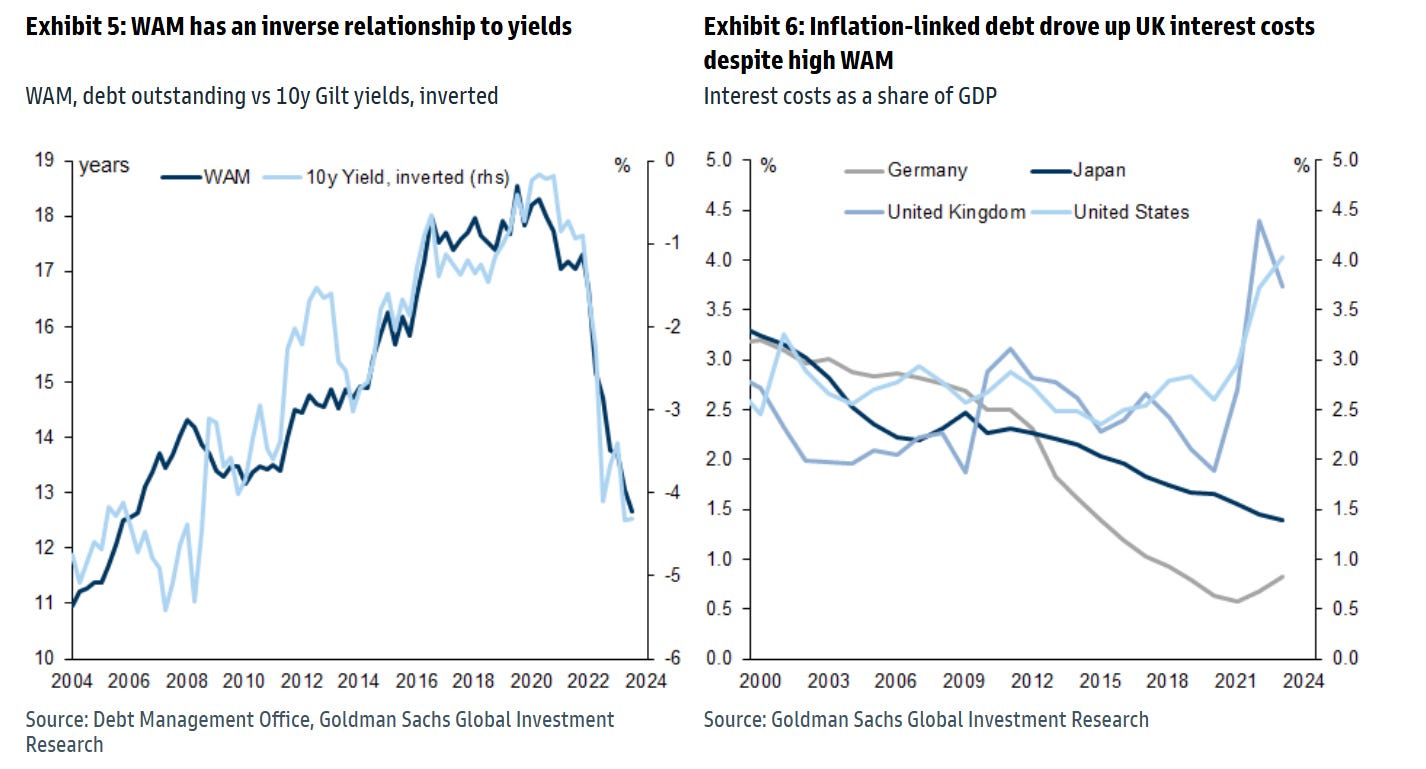

This approach has resulted in the UK maintaining the highest average maturity government bond market globally.

The costs of limiting refinancing risk

But refinancing risk is not one-sided.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can now determine that the UK’s long-dated issuance strategy has proved substantially more expensive than short-dated issuance would have been during the decades-long global bull market in bonds as well as in the current environment where the yield curve is steep.

In an era of declining yields, frequent refinancing could have enabled the Treasury to reduce its borrowing costs incrementally, as opposed to being committed to higher long-term rates.3

Arguably, the most neutral approach to mitigating refinancing risk would be to use exclusively short-term liabilities which, over the course of an economic cycle, would function as natural “fiscal stabilisers,” becoming more costly during economic expansions (when tax revenues are robust) and less costly during downturns (when fiscal support is most needed). This counter-cyclical effect mirrors the rationale often cited for issuing inflation-linked bonds.

In reality, market refinancing dynamics and the unknowable nature of the future makes the exclusive issuance of short-term liabilities likely to be an imprudent debt management policy.

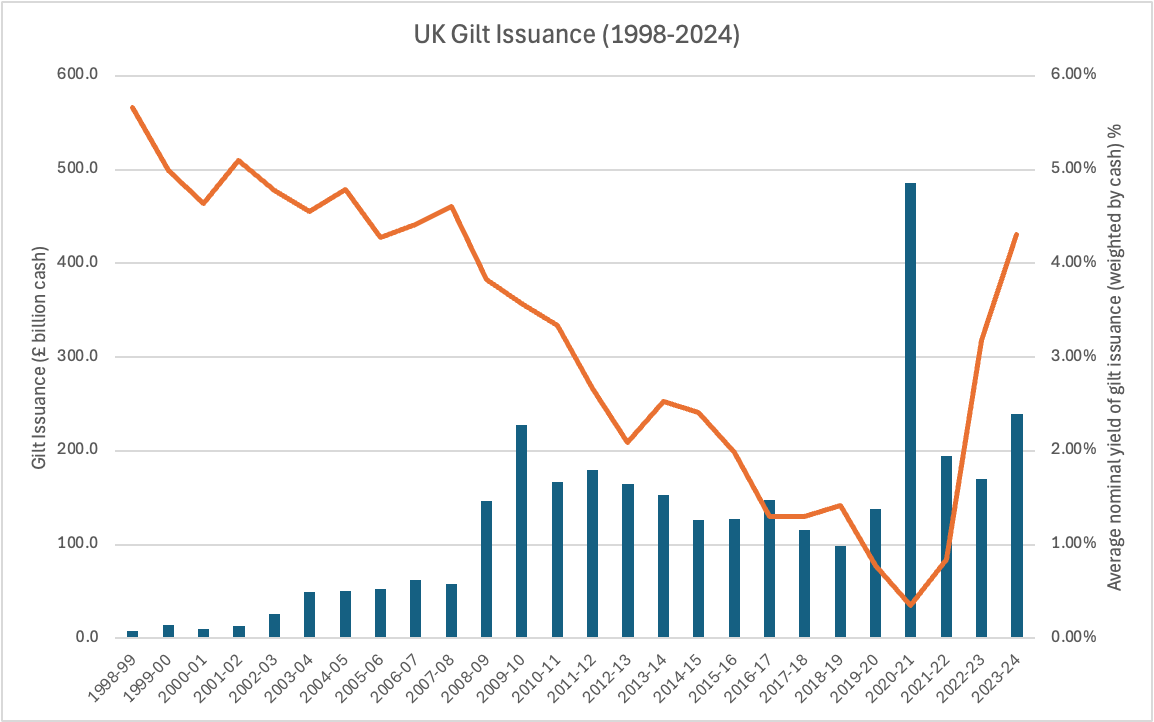

In an ideal world, the government would have issued as much long-term debt at the lowest possible rates. A glance at the below chart indicates that, in a broad sense, this is not dissimilar to what the DMO actually did (although, this was not necessarily by design, but rather driven by urgent pandemic-related current spending which coincided with historically low rates).

The diminishing pension bid for long-dated assets

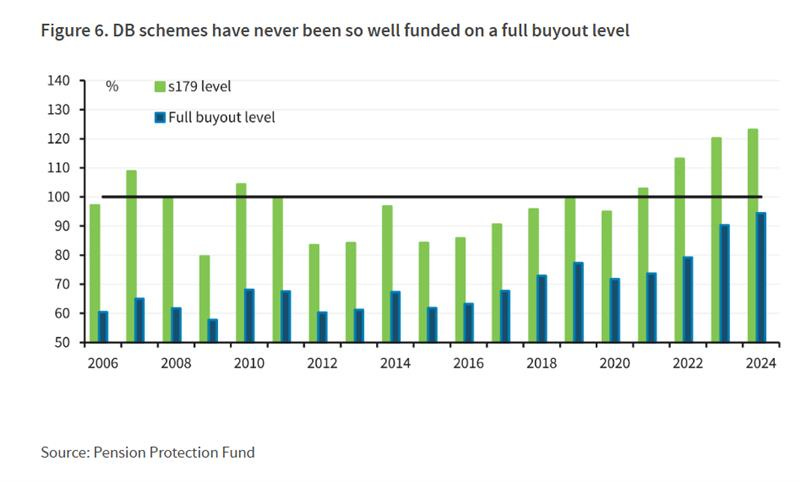

Today, it is also worth noting that there is reduced demand for long-dated gilts from pensions due to a confluence of factors.

Firstly, a substantial portion of pension funds have already transitioned their holdings from equities to bonds, leading to a plateau in fresh demand. Likewise, many defined benefit schemes are no longer open to new members and are experiencing a gradual decline in their membership as beneficiaries pass away.

There has also been a notable reduction in the present value of pension fund liabilities, largely due to a general uplift in yields across the market, which has resulted in improved funding positions for these pensions and lower investment requirement.

How QE distorts the national debt’s maturity profile

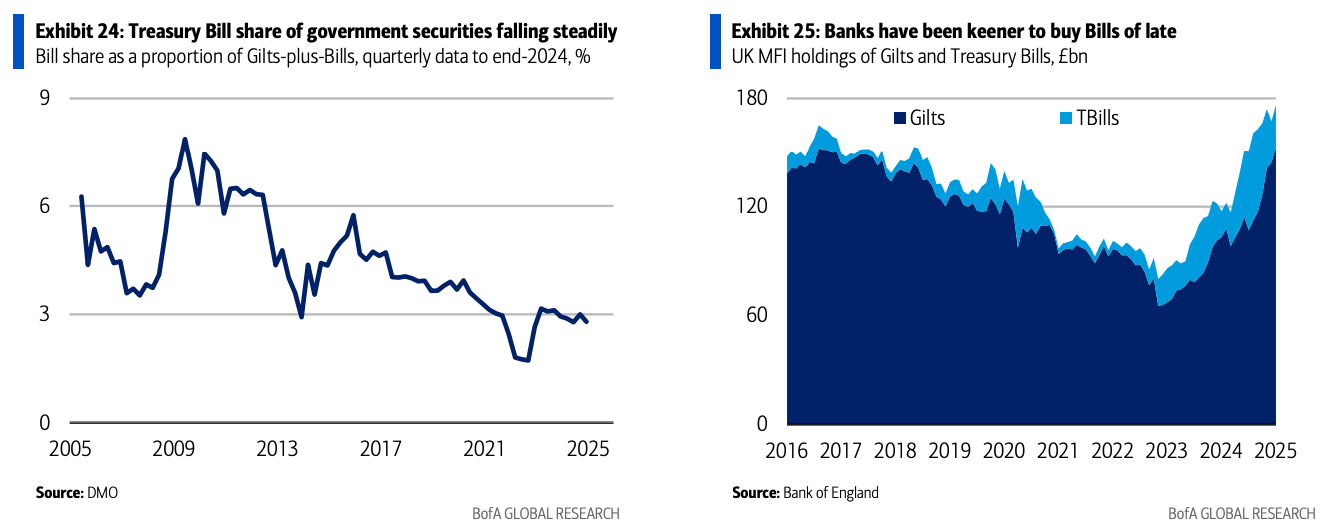

We have established that the UK still has the highest national debt WAM globally and that the favourable dynamics that drove that maturity profile are no longer as relevant.

Therefore, in response to those changes, is the DMO now reducing the WAM of the UK’s debt maturity profile?

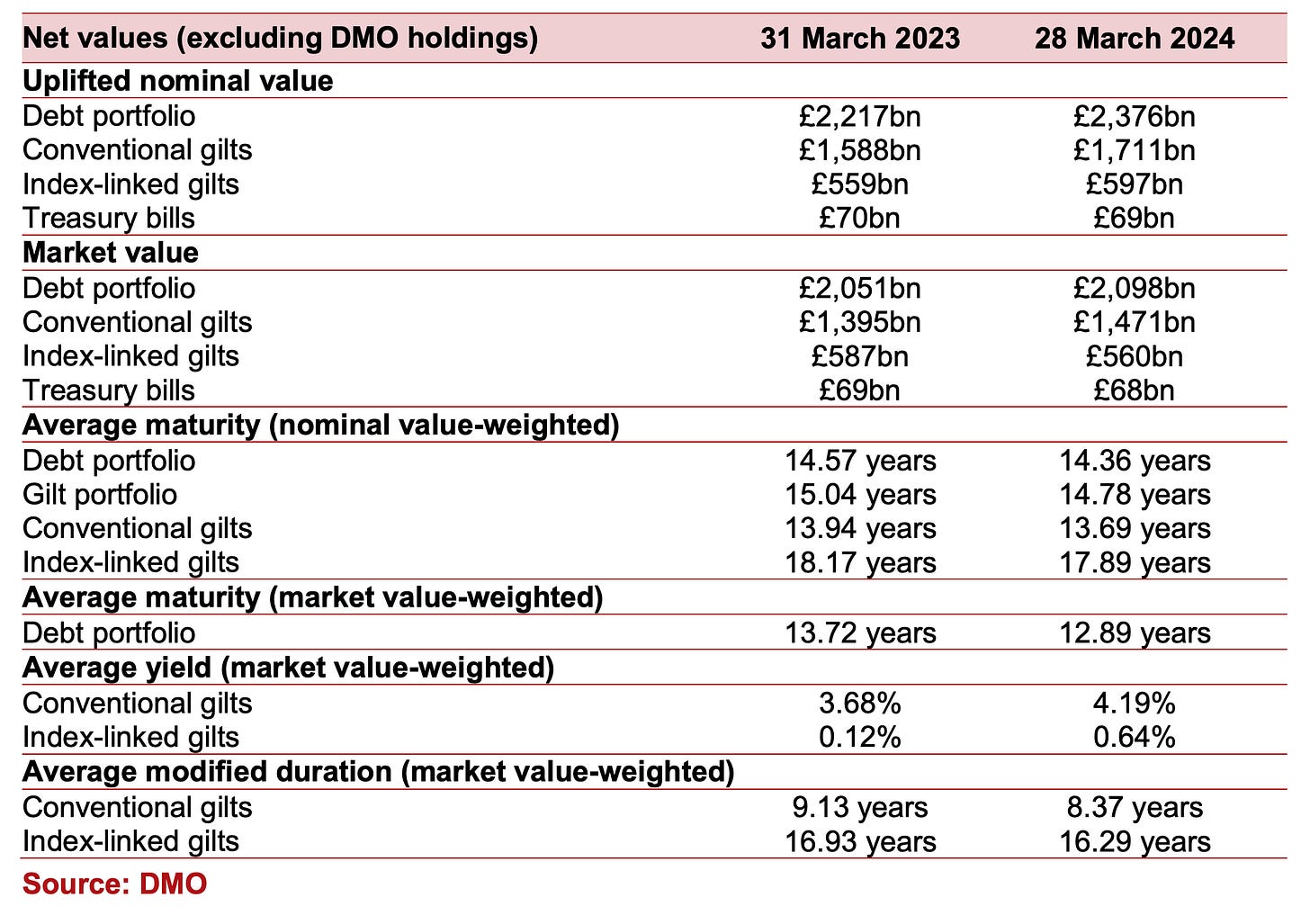

A cursory inspection of the DMO’s Annual review for 2023/24 would suggest that the UK’s weighted average maturity (WAM) is indeed falling. Specifically, the report suggests that the average maturity (market value-weighted) of the DMO debt portfolio has fallen from 13.72 years to 12.89 years.

However, the debt portfolio illustrated in the DMO Review does not reflect the total UK national debt.

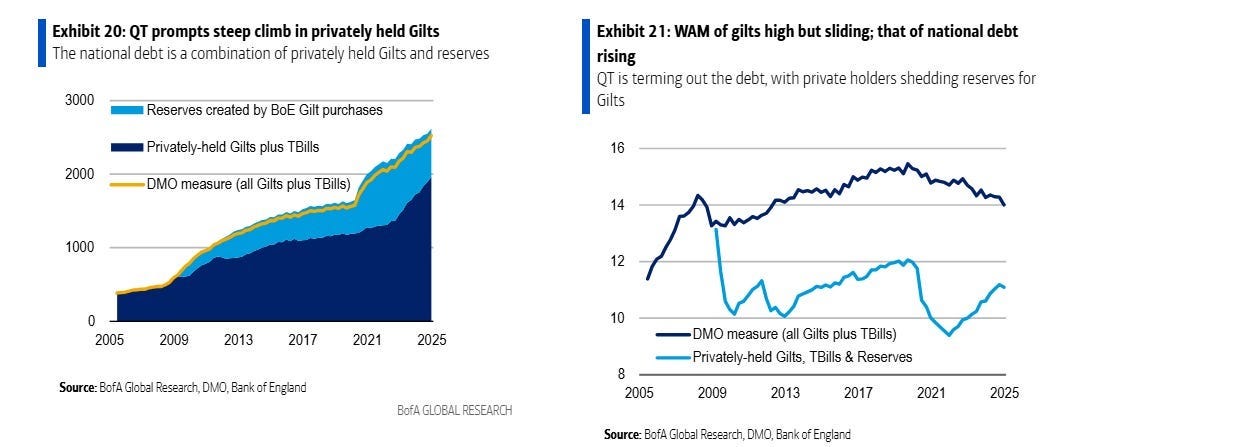

In actuality, the UK national debt comprises both the DMO debt portfolio (gilts and Treasury bills) and the reserves that were issued by the Bank of England to (private) banks as part of quantitative easing operations (in return for gilts and Treasury bills, now held on the APF’s balance sheet).

Although the shorter issuance tilt from the DMO is bringing about a gradual shortening of the WAM of the officially outstanding government securities (excluding APF), the WAM of the national debt (including APF) is increasing through quantitative tightening by the BoE. This is because central bank reserves (which have a WAM of 0 yrs) are being replaced by gilts or bills (with WAM >0 yrs).

Wisdom after the event is unhelpful (everyone has perfect hindsight), but we can now see that the the period of quantitative easing created a significant refinancing liability, not clearly acknowledged at time, nor in keeping with the UK Government, BoE and DMO’s broader debt management strategy. But this phenomenon was recognised by officials from the outset. See, for example, this OBR report from 2021.

In essence, substantial portions of the UK state's long-term obligations, specifically in the form of gilts, were effectively transformed into short-term liabilities, akin to overnight borrowings (reserves).

These short-term liabilities currently incur higher costs compared to the long-dated gilts that were retired. For them now to be replaced by new primary issuance of long-dated gilts would result in an even more punitive cost of borrowing.

How could the DMO reduce the WAM of the UK national debt portfolio?

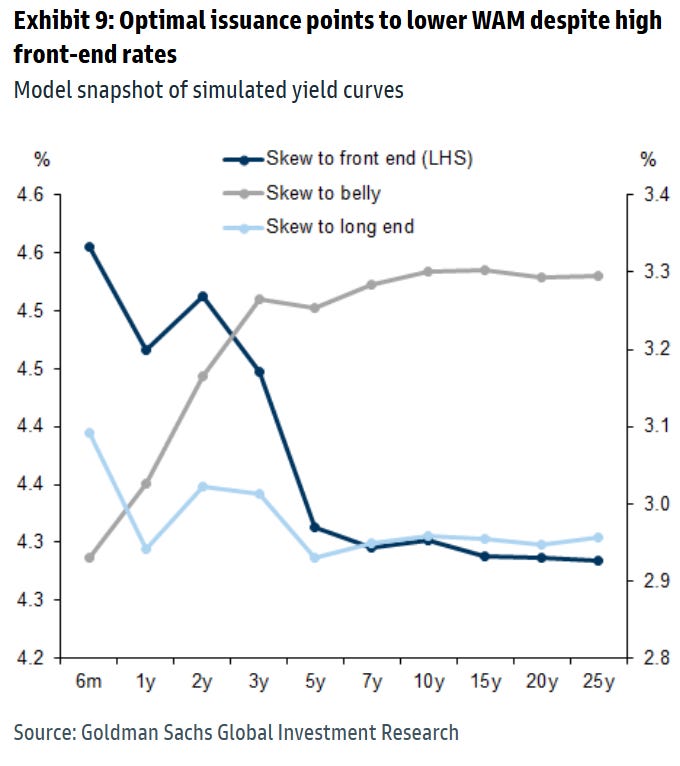

In light of the ongoing central bank programme of quantitative tightening and current market conditions, there is a case for the DMO reconsidering its approach to debt maturity structure.

To me, there seems to be one clear strategic adjustment that the DMO could implement as of today to reduce the weighted average maturity and lower UK borrowing costs; namely:

Increase short-dated Treasury bills primary issuance.

The DMO should increase the volume of issuance of short-dated UK Treasury bills and lower the proportion of long-dated bonds issued.

The UK Treasury bill market remains small by international standards. As quantitative tightening continues, reducing the quantity of Bank of England reserves, this will create natural demand for substitute assets that behave in the same manner.

This is timely as the current steep yield curve makes short-term issuance financially attractive. These instruments would also function counter-cyclically, reducing costs precisely when fiscal support is most needed.

Besides this proposal, if the DMO’s goal was purely to lower the WAM of the UK national debt, there are other strategic options available. For instance, the DMO could strategically tender specific long-dated issues. This would mean:

Targeted buy-backs of long-dated gilts trading at deep discounts would effectively capture “profits” on previously low-coupon issuance.

While governments traditionally view liabilities at book value (indifferent to mark-to-market changes) and prioritise servicing cost stability, the potential to reduce debt-to-GDP by up to 16% (according to BofA analysts) certainly merits consideration.

For example, UKT 4 10/22/63 and UKT 1 ⅛ 10/22/2073 are amongst the cheapest long-dated bonds.

Given, however, that current refinancing costs are higher than some of those historic coupons (0.5% on the 2061s!), it would not be in the interest of the UK to buy back those issues, although it would result in a reduction of the WAM, as it would raise the cost of borrowing (by rolling historic low coupons into much higher current coupons).

For historical precedents for this approach to shortening maturity profiles, see Appendix 1 “Are there historical precedents for shortening maturity profiles?”

Why might the DMO maintain the current approach to WAM?

There are also reasonable explanations for why the DMO might decide to maintain the current debt management strategy. Amongst these, the most compelling are perhaps:

Consistency with policy framework. The DMO's mandate emphasises long-term fiscal sustainability over short-term cost optimisation—a principle that has fostered market stability and investor confidence. Tactical reactions to current yield conditions could undermine this established approach, with historical evidence suggesting limited lasting benefits from financial engineering in sovereign debt management.

Preserving market liquidity. Altering the existing issuance pattern risks fragmenting established benchmark liquidity—a valuable feature developed over decades. The efficiency of the UK's gilt market depends on concentration at key points rather than dispersion across multiple tenors, with fragmentation potentially increasing the liquidity premium across the curve.

Impacts on the repo market. The gilt repo market serves as essential financial plumbing that enables price discovery, supports market-making, and facilitates collateral flows throughout the system. Changes to the UK's maturity profile would inevitably alter collateral availability across different tenors, potentially creating repo market dislocations that could offset intended financing benefits.

Currency diversification

The DMO issues almost exclusively sterling-denominated debt. So, here is a second question:

Could the DMO improve financing costs by issuing bonds and notes denominated in currencies other than sterling (USD/EUR)?

Arguments in favour of issuing non-sterling gilts would be based on the premise that you could lower the cost of capital by expanding the UK's investor base.

By appealing to international investors who prefer holding debt in their native currencies, under certain market conditions, the DMO might secure more favourable borrowing rates in foreign currencies, which could be swapped back to sterling through derivatives markets. Also, there is a case that establishing liquid benchmarks in major foreign currencies would create useful reference points that could benefit UK corporations that issue debt in foreign markets.

As it happens, there are already certain limited instances in which the UK issues short-term debt denominated in foreign currencies (specifically, US dollars and euros).4

But there are also compelling reasons why the UK government issues gilts almost exclusively in sterling. In summary, there are:

Exchange rate risk and monetary sovereignty. These are fundamentally intertwined concerns that militate against issuing foreign currency denominated debt. When issuing debt in foreign currencies, the government not only becomes vulnerable to currency fluctuations but also relinquishes a crucial aspect of its economic independence. If the UK were to issue USD-denominated gilts and the dollar strengthened, the cost of servicing this debt would increase substantially while simultaneously reducing the government's ability to influence these obligations through domestic monetary policy tools. Unlike foreign currency debt, sterling obligations remain under the influence of the UK’s monetary authority. In extreme circumstances, the Bank of England possesses the currency issuance power to meet these obligations – a fundamental safety net unavailable for foreign currency debts. This creates an important distinction between liquidity risk and solvency risk. With sterling debt, the UK faces only potential inflation consequences rather than technical default, preserving its policy autonomy and fiscal flexibility.

Negative financial spirals. Globally, many sovereign issuers do rely on foreign-denominated debt, and their vulnerability to foreign currency obligations can trigger dangerous negative financial spirals during times of economic stress. When investors doubt a nation’s ability to service foreign currency debt, they may sell both the debt and the domestic currency, further increasing debt service costs and worsening the initial problem – a pattern that has repeatedly caused crises in emerging economies reliant on external currency financing, where currency mismatches led to balance sheet crises.

Operational complexity. While currency swaps can mitigate risks, they introduce new complexities and counterparty exposures. The operational infrastructure required to manage a multi-currency debt portfolio is significantly more sophisticated and costly. Given the UK's strong position and robust demand for sterling gilts, the marginal benefits may be limited. Markets might interpret foreign currency borrowing as indicating weakness in domestic funding conditions. Historical episodes of UK foreign currency borrowing, particularly during economic difficulties in the 1970s, have created an association between non-sterling issuance and periods of financial vulnerability.

Moreover, historical episodes of UK foreign currency borrowing have often been associated with economic difficulties, such as in the 1970s. This has left a lasting association between non-sterling issuance and periods of financial vulnerability.5

There are strategies that might mitigate the most problematic exchange rate risks, such as issuing some form of cross-currency swap-linked gilts (instruments with embedded currency hedges to appeal to international investors currently avoiding sterling exposure but which retains UK obligations in sterling). Again, however, these instruments would introduce additional issuer costs through structuring complexity as well as fragmenting the market, potentially reducing liquidity.

Currency diversification benefits do not outweigh the downsides

Given the UK's already strong position in global markets and robust demand for sterling gilts from both domestic and international investors, the marginal benefits of foreign currency issuance are clearly limited.

Likewise, foreign currency debt removes an important policy lever during crises, as it cannot be influenced by domestic monetary policy or affected by inflation in the same way as sterling debt. There's also the perception risk—markets might interpret foreign currency borrowing as indicating weakness in domestic funding conditions.

Range of instruments

Next, lets’s consider the question:

Could the DMO improve financing costs by introducing novel gilt instruments?

The UK gilt market currently consists of:

Conventional gilts (fixed interest)

Index-linked gilts, “linkers” (interest linked to inflation, introduced in 1981)

“Green” gilts (funds committed to “green” projects, introduced in 2021)

The recent introduction of “green” gilts raises the interesting prospect that the DMO could introduce additional novel instruments into its issuance pattern.

It is worth noting how green gilts work. Importantly, green gilts do not work through the hypothecation of the money into certain investments, but rather through commitment structures. The UK government legally pledges to direct gilt proceeds exclusively to environmental projects, publishes detailed allocation reports, and submits to independent verification. This creates accountability and transparency, allowing investors to trace impact without requiring the actual funds raised to be physically segregated or ring-fenced.

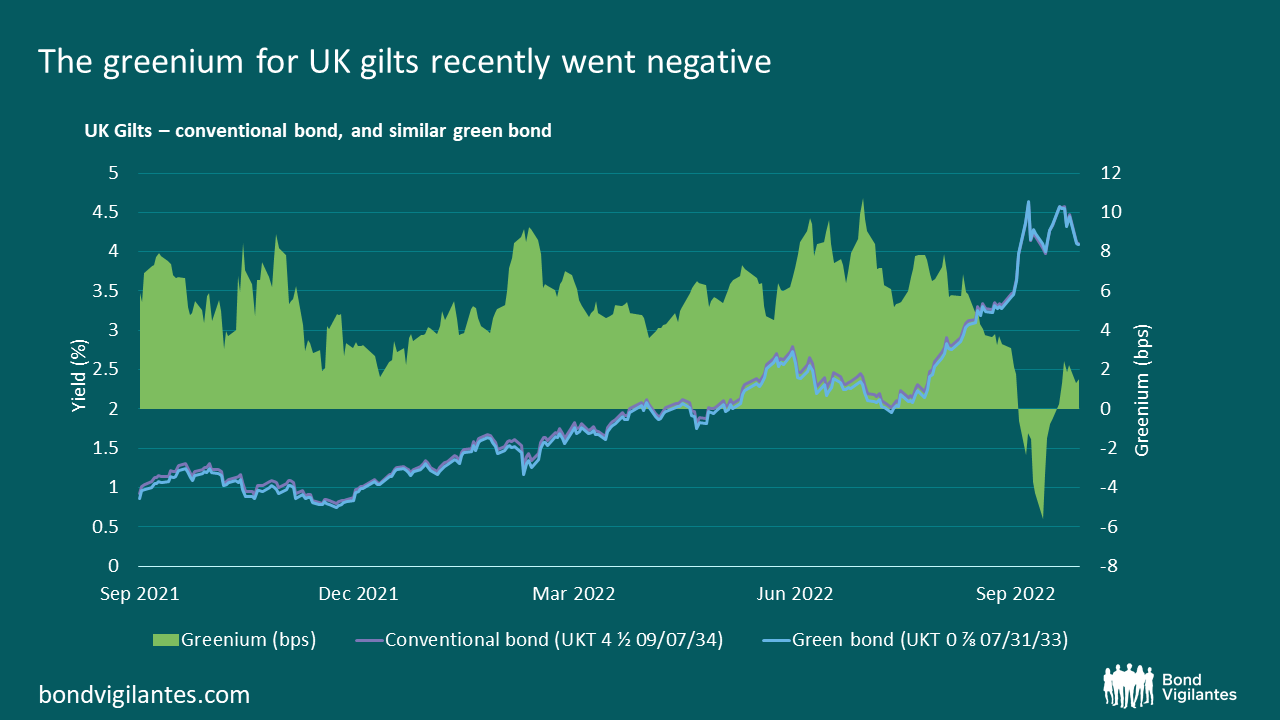

One of the incentives for introducing these green gilts was likely the existence of a so-called “greenium.” Greenium is a portmanteau of “green” and “premium” in reference to the differentiated risk premium that investors are willing to pay for bonds whose funded are committed to green projects compared to equivalent conventional assets.

In theory, the greenium benefits issuers by potentially lowering their borrowing costs due to increased investor demand for sustainable assets, while simultaneously reflecting the price premium those investors are willing to pay for green bonds. However, as with other risk premia discussed above, observing the size of the greenium present in the market is not a simple exercise. A perfect comparison requires there to be two “twin” bonds, one green and one conventional, where the green bond is identical in terms of cash flows and other characteristics to the conventional bond such that there are no pricing distortions caused by differences in capital rank, currency, coupon type, and duration, or the amount outstanding.

Typically, finding matching bond pairs however is not easy, as issuers do not usually issue “twin” bonds. The German Finance agency, however, is an exception and has issued several “twin” pairs of green/conventional bonds (maturing in 2025, 2030, 2031 and 2050). Comparing the yield of these green bonds to the conventional twin therefore enables the greenium to be directly observed. The UK, more typically, does not issue twin bonds. Therefore, the best comparator available to assess the UK sovereign greenium is the UKT 4.5 09/07/2034. Admittedly, this is a bond with slightly lower duration (given the higher coupon structure) and larger amount outstanding, but all things considered it remains a decent proxy.

In reality, like term premium, greenium does not always benefit the issuer. Indeed, at times over the last few years, greenium turned negative. Does this mean that the green-earmarked financing structure in fact increased the cost of borrowing for the UK? Not necessarily. This was more likely the result of a liquidity premium or other technical factors.6

Given the relative success of green gilts, the DMO could consider introducing additional such instruments aimed at broadening the investor base and attracting “ESG”-motivated investors at potentially lower yields.

Consider, for instance, sustainability-linked gilts. SLBs are already commonplace within corporate debt markets and several EM sovereigns have also issued such instruments (Chile and Uruguay). An SLB ties the interest rate of the instrument to a given sustainability target which can ratchet up or down based on meeting specific targets at certain observation dates.

The case against such issuance, besides any reservations around the merits and demerits of such sustainability targets, primarily concern the complexity challenges involved in the operational implementation of such instruments. Significant changes to issuance patterns introduce operational complexities and transition costs that could disrupt market functioning, particularly during periods of stress when predictability in government debt issuance becomes especially valuable.7

Market architecture

Finally, let’s consider a further question:

Could the DMO lower borrowing costs by altering the structure of the gilt market?

Any architectural changes would require gradual implementation to minimise market disruption, leveraging the DMO's established strength in market consultation and transparent communication.

But first, perhaps some historical context is warranted.

Gilt market structure primer

Market structure (1688-1986)

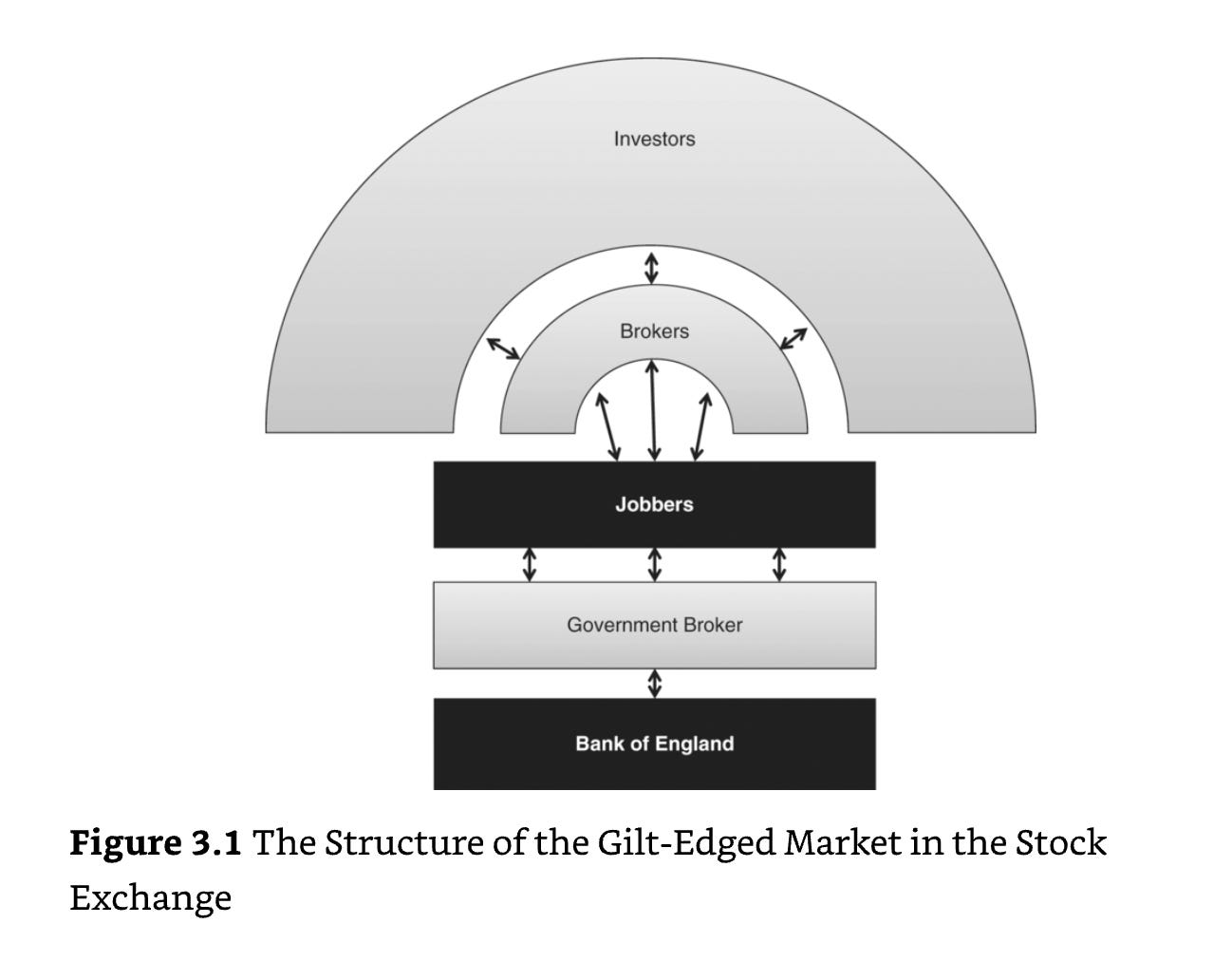

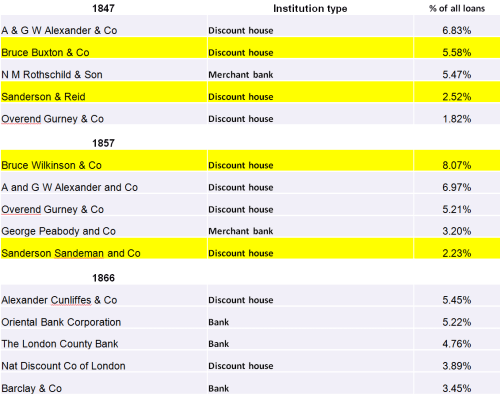

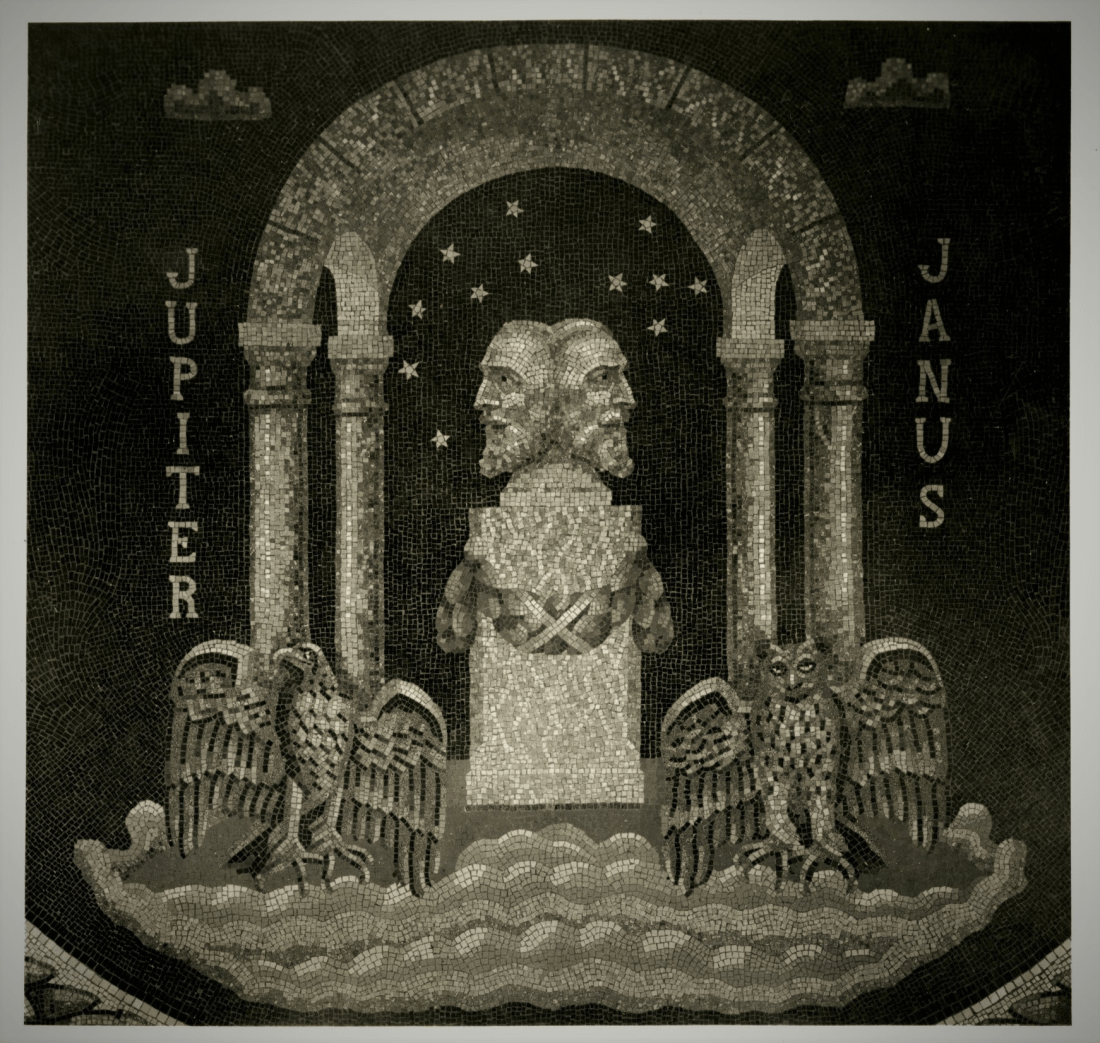

UK government securities have been traded on the London Stock Exchange since the establishment of Britain's permanent national debt following the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

While initially managed as a matter of administrative convenience, government debt management underwent a profound transformation during the 20th century. The extraordinary expansion of the United Kingdom's national debt during the World Wars elevated debt management from a routine Treasury function to an issue of critical macroeconomic significance, fundamentally reshaping both fiscal policy considerations and financial market development.

For primary issuance, from 1909 until Big Bang in 1986, the Bank of England dealt nearly exclusively on the London Stock Exchange, and, not being a member, was obliged to deal through a broker. Its broker, the Government Broker, was the senior partner of Mullens and Co, a stockbroking firm.

During Big Bang, in April 1986, Mullens & Co. was bought out by SG Warburg and ceased to operate. As a result, the brokerage of government securities was broadened, allowing banks and securities houses to register with the Bank of England as brokers, now renamed as gilt-edged market makers (GEMMs).

Current market structure

The architecture of the gilt market has evolved substantially since the Glorious Revolution (and even since Big Bang), adapting to changing market conditions and technological innovations. These transformations have enhanced liquidity, broadened participation, and reduced government financing costs.

Today, in the gilt market, for primary issuance there are three issuance methods that are typically used:

Auctions represent the most common issuance method, following a multiple-price format where successful Gilt-Edged Market Makers (GEMMs) pay their bid price. The DMO maintains transparency by pre-announcing an auction calendar on a quarterly basis, allowing market participants to plan accordingly.

Syndications are used for large, often long-dated or index-linked issues. The DMO appoints a group of GEMMs to form a syndicate that markets the gilt to investors, building an order book. This method allows for larger issuance volumes and targets specific investor bases.

Taps are smaller offerings of existing bonds addressing specific market demand or liquidity concerns, enabling the DMO to respond flexibly to market conditions.

Here are two additional areas where further architectural changes might yield benefits.

“Market maker of last resort” programme

In his canonical text on financial markets and central banking, Walter Bagehot outlined the following principles for crisis management:

In time of panic [the central bank] must advance freely and vigorously to the public out of the reserve… for this purpose there are two rules:

First. That these loans should only be made at a very high rate of interest. This will operate as a heavy fine on unreasonable timidity, and will prevent the greatest number of applications by persons who do not require it.

Secondly. That at this rate these advances should be made on all good banking securities, and as largely as the public ask for them. The reason is plain. The object is to stay alarm, and nothing therefore should be done to cause alarm. But the way to cause alarm is to refuse some one who has good security to offer.

Walter Bagehot, Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market, Chapter VII.II (1873)

Throughout its history (even prior to the publication of Bagehot’s text), the Bank of England acted as a lender of last resort role at times of financial market crisis. This happened on several occasions across the 19th and 20th centuries, as it has again in the 21st century, most recently during the 2008 financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and 2022 LDI crisis.

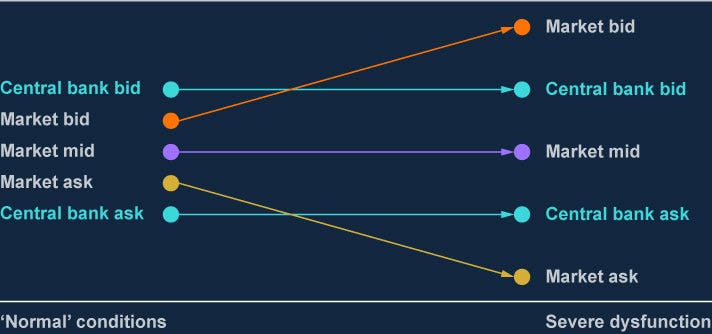

Today, one of the most significant architectural innovations that the Bank could implement would be to establish a formal “Market Maker of Last Resort” (MMLR) framework to preserve financial stability during periods of severe market dislocation.

This could take the form of a formal commitment to intervene in gilt markets during periods of exceptional stress, not as an emergency measure but as a structured market function with predefined activation thresholds, operational protocols, and exit strategies.

This could be achieved by means of a two-way stabilisation mechanism, as outlined in a recent Bank of England bulletin. The central bank would establish bid-ask prices outside competitive market rates during normal conditions, discouraging usage of its facilities. When markets become severely dysfunctional, these unchanged central bank prices would automatically become attractive, activating the Market Maker of Last Resort function precisely when needed.

This mechanism honours Bagehot’s principle of lending at penalty rates whilst providing essential liquidity during crises—all through a transparent framework that minimises moral hazard and preserves financial stability.

Crucially, the MMLR function would differ from quantitative easing in both scope and intention—focusing specifically on preserving market functioning rather than pursuing broader monetary policy objectives. Unlike traditional asset purchase programmes, an effective MMLR would operate symmetrically, both buying and selling gilts as needed to maintain orderly markets. This two-way mechanism would distinguish it from quantitative easing programmes and position it more clearly as a market functioning tool rather than a monetary policy instrument.

Strategic liquidity concentration

A final change that the DMO could implement would be a deliberate strategy to concentrate liquidity in fewer, larger benchmark issues.

If applied, such a benchmark concentration strategy would focus on creating standardised “super-benchmark” issuances at key tenors rather than maintaining a diverse range of gilt issues across the yield curve. This approach, already employed successfully by the US Treasury and Germany's Deutsche Finanzagentur, enables more efficient price discovery and potentially narrower bid-ask spreads.

However, this strategy also presents potential drawbacks that may outweigh its benefits. Concentrating issuance would reduce the precision with which liability-driven investors can match their duration needs, potentially decreasing overall demand from the UK's pension-heavy investor base. Larger benchmark issues would also create more pronounced refinancing “cliffs,” increasing cash flow volatility for the government.

Given that the UK gilt market already functions well in normal liquidity conditions, the marginal benefits of further concentration are unlikely to justify the associated risks and market disruption. By contrast, the MMLR function formalises a role that is already crucial during periods of price dislocation.

Concluding thoughts

On setting out to write this piece, my intuition was that institutional conservatism has likely prevented the deployment of novel strategies in debt management.

On reflection, this concern seems largely unfounded. The existing framework, particularly regarding currency denomination and instrument selection, represents a rational response to the UK’s specific market dynamics.

There are, however, two areas for which there is compelling evidence for adjustment.

First, the public debt maturity profile. The historical long-dated bias, once aligned with structural pension demand, now appears increasingly misaligned with current market dynamics. This is compounded by the fact that quantitative tightening is reducing the quantity of central bank reserves increasing demand amongst banks for substitute assets, such as short-dated gilts.

In short, a modest shift towards increased Treasury bill issuance could potentially reduce borrowing costs whilst maintaining the existing strengths of the UK’s debt management approach.

This is by no means a novel proposal. The papers by Goldman Sachs, Bank of America and Barclays that I have referenced each touch on the possibility of such developments in the UK’s debt maturity profile. Officials at the helm of other major central banks are also reflecting on similar challenges.8

Secondly, a further structural change that the Bank might also wish to consider is the establishment of a formal “Market Maker of Last Resort” (MMLR) framework to preserve financial stability during periods of severe market dislocation. This proposal is grounded in the sound principles set out by Bagehot in the 19th century and a viable mechanism has already been outlined by Bank of England officials themselves.

Finally, it is worth stating that any such adjustments should be implemented gradually and transparently, ensuring that reduced borrowing costs are not offset by market disruption or increased risk premia.

Bibliography

Bank of England:

The yield curve impact of government debt issuance surprises and the implications for QT. November 2024

Financial stability buy/sell tools: a gilt market case study. November 2023

The Bank of England as lender of last resort: new historical evidence from daily transactional data. November 2017

Debt Management Office:

GEMM Guidebook, October 2024

Information Memorandum Issue, Stripping and Reconstitution of British Government Stock, March 2024

Official Operations in the Gilt Market, March 2024

Office for Budget Responsibility:

Debt interest (central government, net of APF). February 2025

Debt maturity, quantitative easing and interest rate sensitivity. March 2021

Financial Times:

Bessent’s debt dilemma. Robert Armstrong, March 2025

Yields up, (long-dated) borrowing down? Toby Nangle, March 2025

Lessons from the gilts crisis. John Plender, December 2022

‘Who is going to buy?’ UK set to unleash historic debt deluge. Tommy Stubbington, December 2022

UK’s debt management chief gets set for fresh borrowing binge. Tommy Stubbington, January 2020

Investment Industry Research:

Bank of America. Choices under pressure. An ambitious UK Treasury has options to tame Gilts. Mark Capleton et al, 19 March 2025

Bank of America. Who pays wins. How UK DMO can still deliver duration with short-dated issuance. Market Capleton et al, 23 February 2023

Goldman Sachs. Shorter WAM Optimal for Gilts. George Cole et al, February 2024

Barclays. Why the long face? Moyeen Islam et al, 12 Februrary 2025

Hudson Bay Capital. ATI: Activist Treasury Issuance and the Tug-of-War Over Monetary Policy, July 2024

M&G Bond Vigilantes: There’s no free lunch in green bonds… or is there? October 2022

William Allen:

The following two texts are valuable contributions to the historical study of UK debt management.

Mr Allen worked for the Bank of England from 1972 to 2004 in a wide range of functions, including monetary policy formulation and financial market operations. From 1978 to 1980 he was seconded to the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland, and from 1994 to 1998 he was a member of the European Union Monetary Committee.

Government debt management and monetary policy in Britain since 1919, Bank for International Settlements Papers. 2012

Paper comparing four episodes in the management of the UK national debt since 1919.

The Bank of England and the Government Debt: Operations in the Gilt-Edged Market, 1928–1972 (Studies in Macroeconomic History). 2019

Book narrating official interventions by the British monetary authorities in the secondary market for gilts from 1928 to 1972.

Considers how the market for gilts developed in the middle of the 20th century, of how the monetary authorities tried to compensate for its deficiencies, and of how they overcame the unintended consequences of their actions.

Appendix 1: Historical precedents for shortening maturity profiles

US Treasury's 2001 decision

The US Treasury successfully employed buyback operations to improve market liquidity and manage its maturity profile. During 2000-2002, for instance, the Treasury used budget surpluses to repurchase less liquid off-the-run bonds, enhancing overall market functioning and reducing the government's borrowing costs by an estimated 1-2 basis points—significant savings when applied to a multi-trillion-dollar debt stock.

When the US Treasury announced the suspension of 30-year bond issuance on 31 October 2001, the market reaction was immediate and dramatic. The 10-year yield fell 18 basis points (from 4.41% to 4.23%) while the 30-year yield dropped 34 basis points (from 5.21% to 4.87%) in a single trading day. This sharp bull-flattening of the curve demonstrated how central banks can significantly influence both yield levels and curve shape through strategic issuance decisions. The US was operating with budget surpluses at the time, making the comparison imperfect but instructive.

UK debt management in the early 1980s

During the early Thatcher years, the UK Treasury deliberately shortened its issuance profile, refusing to pay what it considered excessive term premiums for longer-dated debt. This strategy coincided with a period of significant yield curve adjustment and contributed to reshaping market expectations about future government funding patterns. Though implemented under different economic conditions—with inflation much higher than today—this episode highlighted how determined policy shifts in maturity structure can influence market pricing.

Additional international examples

Several other countries including Canada (2017), Germany (2008) and Australia (2011) have at various times adjusted their maturity profiles in response to changing market conditions, generally achieving measurable impacts on their respective yield curves. These interventions typically produced the most significant effects when they represented clear departures from established issuance patterns rather than incremental adjustments.

These events happened in different fiscal circumstances, but they demonstrate that debt management offices can have a material effect on the level and shape of the yield curve by changing the distribution of debt issuance.

SONIA futures dominate the front end (0-5 years), offering efficient short-term exposure with tight bid-ask spreads. Gilt futures provide superior liquidity for medium to longer-term exposures (centred around the 10-year benchmark), while interest rate swaps remain actively traded across all maturities from overnight to 50+ years. This complementary structure enables market participants to efficiently execute trades, manage complex exposures, and express nuanced views across different segments of the sterling yield curve.

Not least expectations around fiscal policy, future government spending, taxation policies, debt sustainability, and their potential impact on economic growth rates and public debt dynamics. It is the continual interplay of these elements, along with global economic trends and geopolitical developments, that collectively informs investor sentiment and influences yield movements.

From the bond investor's perspective, this dynamic explains why long-dated gilt indices significantly outperformed both their shorter-dated counterparts and strategies that involve rolling over Treasury Bills. As the counterpart to these investment positions, the Treasury has effectively borne these elevated relative costs, although it does not value its liabilities on a mark-to-market basis as investors do with their assets, so does not necessarily recognise these costs.

Typically, this has been for the purpose of managing foreign exchange reserves rather than for financing budget deficits, and during periods when sterling has been under significant pressure, foreign exchange reserves needed bolstering, international financial institutions required specific financing arrangements, or special policy objectives necessitated foreign currency issuance

The UK government has historically issued non-sterling debt during periods of economic difficulty. After World War II (1940s-1950s), Britain borrowed heavily in US dollars, notably through the 1945 Anglo-American Financial Agreement worth $3.75 billion, when foreign exchange reserves were severely depleted. During economic crises in the 1960s-1970s, foreign currency bonds became necessary, particularly during the Wilson government's sterling crises (1964-1967) and most significantly in 1976-1977, when IMF assistance required foreign currency securities issuance amidst a dramatic pound devaluation.

Likewise, following the euro's introduction (1999), the UK issued limited euro-denominated securities, generally for specific policy objectives rather than financial necessity. The government has occasionally used the European Union Medium Term Note Programme and issued Foreign Currency Treasury Bills in dollars and euros, though primarily for managing foreign exchange reserves rather than financing budget deficits.

M&G propose that it may be the result of “green corporate issuance which let some bigger accounts sell the green gilts and move into corporate green deals, or the fact that the green gilts got caught in the midst of the Cheapest-To-Deliver battle for the future contract between the Gilt 32s and 34.” M&G

NB: In a future post, I intend to share a post discussing the relative merits of the various debt financing instruments and vehicles that governments may use to fund the development of utility infrastructure projects (such as water, energy, telecommunications), with specific reference to nuclear small modular reactors.

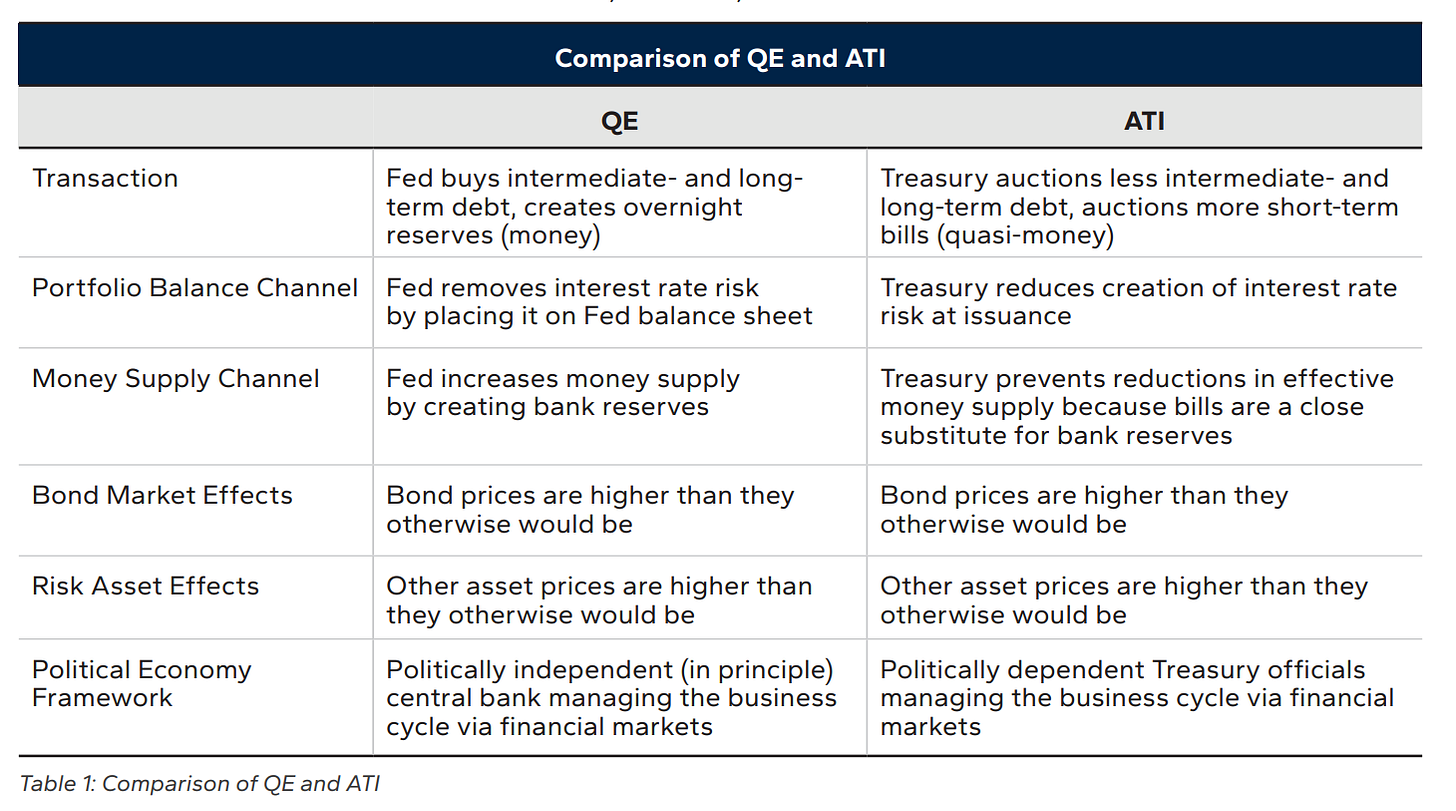

In a widely circulated paper, the incoming chair of the US Council of Economic Advisers has argued that issuing more short-term Treasuries artificially lowers longer-term yields (“Activist Treasury Issuance”, or ATI), allowing the government to run up bigger deficits and stimulate the economy without spooking bondholders. Hudson Bay Capital. ATI: Activist Treasury Issuance and the Tug-of-War Over Monetary Policy, July 2024